With its “Lives Lost” series, The Gazette is remembering those whose lives were cut short by the COVID-19 pandemic. But the impact of the pandemic is felt in other ways, too. With “Lives Left Behind,” The Gazette is profiling those who have lost not their lives but their livelihoods, who have been forced to put their dreams on hold or struggled to keep their businesses afloat as the coronavirus keeps its grip on the world.

John Mesa was 16 years old when his dad was murdered in a paid hit ordered on the wealthy native of the United States territory of Guam.

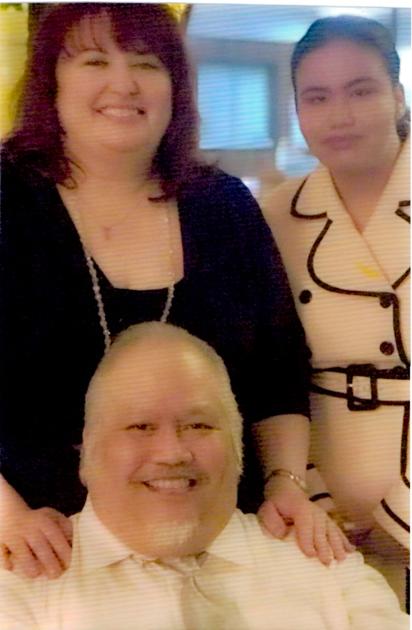

More than four decades later, John’s daughter, Alexandria, now nearly the exact same age, has lost her dad from another unexpected lethal blow.

John, 60, died Dec. 6 at a hospital in Colorado Springs from complications of COVID-19.

The circumstances may be worlds apart, but today’s killer leaves behind just as raw and gut-wrenching sorrow.

“It’s such a weird coincidence, with totally different reasons, but the loss is still so hard,” said Vern, John’s wife of 18 years.

John and Vern met at Lighthouse Temple, the church Vern’s parents founded 62 years ago. The evangelical, charismatic church is known by anyone who travels on the west side of Colorado Springs because of the large illuminated cross on its property atop Sugarloaf Mountain.

The cross hides a cellphone tower these days but continues to serve its original intent as a sign of hope and a beacon to all.

“Our city bravely allowed the right to plant the great lit cross on the point of the peak, shining in the night, and holding out its arms in day,” an old church document says. “We know that many have looked to the cross, in their time of trouble, for comfort.”

John, also a Guam native but whose family relocated to California when he was a teen, did not take his father’s death well and began using drugs and drinking.

After his father’s murder, John and his mother moved to Colorado Springs, where they had relatives. During the long drive, John made up his mind to stop his bad habits.

He stayed true to that conviction.

John volunteered as a Sunday school teacher, a greeter, an usher and a deacon at Lighthouse Temple, where up to 150 people worship during normal times.

“He was somebody that made everybody feel comfortable, nobody felt like a stranger,” said Vern, the youngest of five children of the late R.G. and Vernice Dunbar. Her brother, Robert Dunbar, and his wife, Carol, now are the pastors.

John also had a good sense of humor, said Tammy Scott, one of Vern’s sisters who knew John before he started dating Vern.

Tammy considered John “a pal.”

“He was the most personable guy you’d ever meet,” Tammy said. “He was charming, handsome and very dapper. He could put a suit and tie together like nobody else.”

Though they practice the Christian faith and believe John is in heaven and his body is free from struggles, family members feel broken without him, Tammy said.

“I miss him, and I know my sister misses him terribly,” she said. “It’s a big hole in our family.”

The last time Vern saw her husband in person was the day before Thanksgiving, when he was being pushed in a wheelchair from Memorial Hospital Central’s emergency department to an in-patient room, after being diagnosed with COVID.

Thirteen days later, he was gone.

“We were shocked we couldn’t talk to him or see him,” Vern said about the day he was dying.

But mother and daughter were able to say goodbye to their beloved John on video chat, with the help of an Intensive Care Unit nurse.

“He couldn’t see us or talk to us, but we told him all the things we needed to say,” Vern said, crying. “We told him we’d be OK.”

John looked peaceful, she said, which was like a balm for their hearts.

Vern, a driver for Uber and Lyft, said she has no idea how her husband caught the novel coronavirus.

John had several careers, including moving up from busboy at a Denny’s to cooking at the restaurant to training new cooks. He also sold cars for a while and worked in technical communications support.

Diabetes and other underlying health conditions had zapped his strength just before COVID began spreading last spring, and the couple was in the process of signing him up for medical disability benefits.

As the pandemic intensified, John didn’t leave the house much and spent time with Alexandria, as she did school at home.

Somewhat presciently, John told Vern if he got the virus, he didn’t think he’d make it.

Two days before Thanksgiving, John called Vern at work and said he didn’t feel good. When she got home, he didn’t look good and was weak. Vern told him she wanted to take him for emergency treatment, and John didn’t argue.

Neither realized he had COVID.

It took nearly a day for a bed to open up at the hospital, and Vern and Alexandria were told to go home and quarantine, as they likely had the virus, too.

For the first week, they talked with John on the phone, and he seemed to be faring all right.

“They were saying he was doing well,” Vern said. “It never dawned on us he could die.”

But John developed pneumonia, his breathing became labored, and he was moved to ICU, where he was intubated. Vern and Alexandria could only look at him on video conferencing.

“We had a false sense of security,” Vern said. “It changed so rapidly.”

The nurse called Vern on the morning of Dec. 6 to say John had had a bad night and was failing. He died that afternoon.

Vern noticed during the video chat that the nurse patted John’s head in the exact same way Vern had done, which she said was a comfort to her.

“The nurse didn’t know how John liked his back or head rubbed, but to know that John left this world with someone stroking his head just as my sister did was a godsend,” Tammy said.

Alexandria, a Coronado High School student, is stoic and glad that her dad isn’t in pain anymore, Vern said.

With cremation and funeral services backed up, it took a few weeks to get John’s ashes home. Then came the holidays.

John’s memorial service was held Jan. 17 at Lighthouse Temple, where Vern said so many people offered their condolences and support that it helped with the family’s grieving process.

“We thank everybody for standing with us,” Vern said. “John would have been proud of everybody who did that for us; he always felt like that was his job.”

This content was originally published here.