One of the many joys of old newspapers is reading with the benefit of hindsight. It is with this hindsight that I wish to explore 1920s newspapers for this installment of A Window To History, courtesy of the Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection (CHNC). As we live through our own third decade of the century, unsure of how these Twenties will be recalled in the next century, let us cast our minds back to that glittering decade of the twentieth century.

Not all journalists in the early 1920s knew, or seemed to know, that they were living through one of the most memorable – and modernizing – decades of the 20th century, a time of dramatic social, artistic, and cultural changes, as well as a time of prosperity in America, bouncing back from the devastating First World War, and ending with the Great Depression.

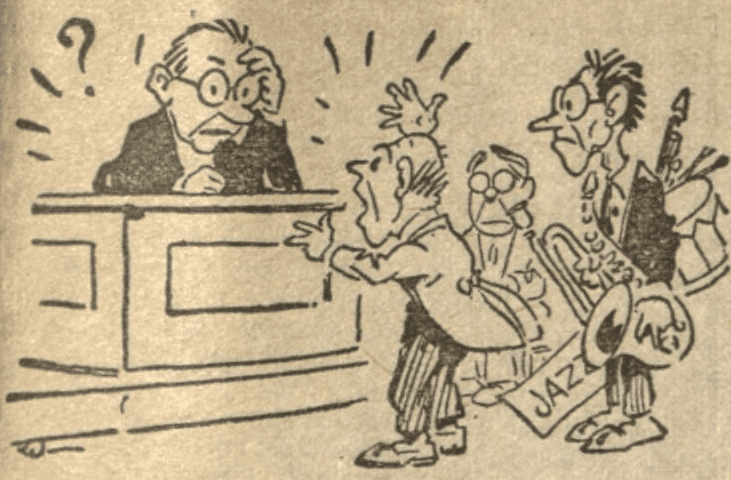

Take, for example, the article ‘Is Jazz Real Music or Just Tomfoolery?’ from The Eagle County News, dated October 2, 1920:

Mario Armeline, former orchestra leader at a fashionable Washington hotel, has appealed to the courts to decide this momentous question. Armeline contends it is not. He was dismissed because he couldn’t play Jazz. Now he is suing for breach of contract.

“Evoked out of sheer sensationalism, ramified by an ill-placed enthusiasm on the part of the unmusical, commercially exploited to the ‘nth’ degree. Jazz has had its day…”

Clearly, jazz’s day was only just beginning. It is sort of strange to observe how controversial this relatively new musical genre really was at the time. To a lot of folks, Jazz represented modernity and change, a move away from the old ways. The whole decade is marked by this tension: big changes were afoot.

The conflicts of the old versus the new was perhaps made clearest in the politics of the day. Although Coloradan women had been eligible to vote since way back in 1893 (making Colorado the first state to secure women’s voting rights by popular vote), the 19th Amendment to the US Constitution was adopted on August 26, 1920, finally granting all American women the right to vote. The ratification of the 19th Amendment prompted questions from the establishment. A WOMAN PRESIDENT?, asks a palpably incredulous Eagle County News on November 6, 1920.

A WOMAN for President of the United States? It’s an interesting question, anyway, now that the federal suffrage amendment has been ratified, and women are voters. And there’s nothing new or startling about it. Many men are asking themselves the question—to say nothing of what the women may or may not be thinking on the subject. Buttonhole any intelligent man and ask him what he thinks and it’s likely he’ll talk about like this: ‘I would not be surprised to see a woman candidate for the presidency before long. And four years from now they’re quite likely to be demanding—and getting—the vice presidency on one or both of the two leading party tickets. By the time the next presidential election gets around the women will have found themselves as politicians and will be in shape to make their power felt. They’ll certainly put in a claim for a cabinet position or two and for some of the important elective or appointive offices. We might do worse. There are plenty of mighty capable women in this country, and “a new broom sweeps clean,” you know.’

A byproduct of the progressivism that culminated in the Twenties was the flapper. Flappers were often a subject of derision or used as a symbol for what reactionary journalists considered to be a moral decay sweeping the nation. Take the article published in The Moffat County Bell on September 1, 1922, ‘Modern Girl Has No Heart, No Soul—If She Has She Will Not Admit It‘ which, although extremely offensive by today’s standards, seemed to display commonplace opinions:

The modern girl has no heart, no soul, no sentiment—if she has she refuses to admit it. You do not dare to talk to the flapper of classics nor of other serious things, for she simply will make no attempt to absorb them. She is idle, frivolous and heedless of tomorrow. However, I will admit that she is charming and often irresistible.

She looks so young, but knows so much—much, that she could do well not to know. She assumes no responsibility. She seeks nothing but amusement. When a boy reaches the flapper age he usually has some obligation to fulfill. He gets a job, or else he is branded as a loafer. The girl, however, spends her time reading frothy literature and smoking. In my opinion the only hope of the nation rests upon the working girl. She has more originality and individuality than the flapper, who looks to me ns if she were made from a die. Each working girl has her particular style in clothes and coiffure. But the flapper! How can you tell one from another?

To others, though, flappers represented a broadening of what a woman could be, one who had agency and transcended prescribed societal roles. From the Denver Clarion (University of Denver paper), November 26, 1925:

University of Denver coeds like to be called “flappers,” is the verdict of an investigator who is preparing a thesis on modern slang. In the past month he says he interviewed 568 girls at odd moments, when they least expected it, and they all voted for flapper. Some were in favor of calling themselves “moderns,” but they were in the minority, altho the word “flapper” carries an idea that characterizes the coed as insincere, trivial, flirtatious, and beautiful but dumb. A similar survey carried on at Boulder, however, shows that the sophisticated ladies at the university consider “flapper” outgrown and inadequate. No less than 69 per cent of those interviewed declared themselves overwhelmingly in favor of being known as “moderns.” How about it, girls?

(I wonder what exactly is meant by “he interviewed 568 girls at odd moments, when they least expected it…”)

The Twenties saw the mass production of cars on a scale never before seen, echoing the greater reality that America was undergoing a period of great prosperity. By the end of the decade, the Ford Model T was supplanted by the new Model A, and by then automobiles were no longer considered a luxury good. Convenient though it was, the automobile of the time could be temperamental. This article from The Mesita Herald, April 16, 1920, details the woes of an unfortunate owner (which somehow made the news).

Probably every autoist has at some time or other tried to run his automobile without gasoline. It’s all right for a joy rider, but hard on a physician, as Dr. E. Hawkins, of Greencastle, can testify.

A few nights ago Dr. Hawkins had a midnight call west of the city. While returning home and on a lonely stretch of road, his auto gave a cough, another cough and died in the middle of the road. Not until then did the doctor think of his empty gas tank. It was too late. He walked a mile to the nearest farm house, roused a sleepy but obliging farmer, borrowed a gallon of gasoline and walked a mile hack to the auto. He poured the gas in the tank and expected soon to he home, but he was doomed to disappointment. He had the carburetor set for a “high test” gas and the common fuel refused to respond.

After repeated efforts and adjustments Dr. Hawkins got the motor started, but in the meantime he had used most of the gallon of gasoline and when he started for home, the car soon went dead again. Then another long walk and the rousing of another sleepy farmer to get to a telephone and the doctor had help sent out from a local garage. He got home, but not until in the wee small hours of the morning and with the old saying “never again” firmly impressed on his mind.

Surely one of the most interesting decades in US history, CHNC has tons of material from the 1920s. Oh, and if you’re curious about the huge cat that waddles like a duck, let me share the entire article, which raises so many questions.

RELIEVES FLAPPER GHOST

Huge Feline With Web Feet Gives New Yorker Real Scare Waddles Like a Duck.

Millerton, N. Y.—A new character in the form of a huge cat that has web feet and waddles like a duck, has been added to the story of the flapper ghost, which is on the tongues of Millerton’s citizenry. The appearance of this feline apparition vouched for by a male guest, who passed the night in the home of Theron Snyder, where the flapper ghost makes its visits. The guest had gone to bed and was waiting for the flapper ghost to peep in at the window, when the cat waddled into the room. The guest ducked his head under the cover, and he swears a mighty oath that the cat climbed onto his chest and did a goosestep with its web feet. He screeched, so the story goes at the village store, yelled “Scat!” at the top of his voice und vacated the room. A lamp was lighted and a thorough search of the room was made, but the ghost cat had disappeared.

This content was originally published here.