Editor’s note: This month, as Colorado Springs gears up for its 150th birthday on July 31, The Gazette has prepared a series of articles on the history of our city. Check back for fascinating glimpses into the people and events that have shaped Colorado Springs into the landmark it is today.

Iconic and historical buildings in Colorado Springs help serve as reminders of key eras — the wealth of the gold mining days can be seen in the Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum, and the tuberculosis huts scattered around the city help remind us of when patients flocked to town for the dry air.

However, beloved buildings — perhaps too many — were lost over the decades. In some cases the buildings were torn down despite the pleas from citizens. Some were lost in the push for urban renewal downtown, and others came down because private owners considered them too costly to save.

What follows is a small sampling of lost and saved landmarks.

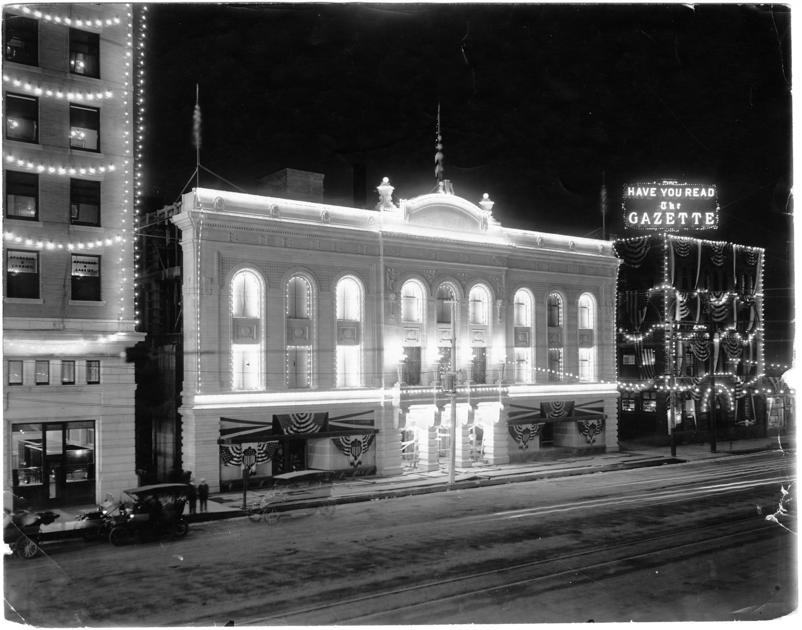

The Burns Theatre

The interior of the Burns Theatre, shortly after opening, is seen in this 1912 photograph. On opening night, a Russian symphony played to an audience of 1,500. The Burns later became the Chief movie theater, and the Chief fell into disrepair. After the Exchange National Bank bought the building in the early 1970s, it tore it down to create a drive-up bank.

Perhaps the most famous lost building in town is the Burns Theater, built by millionaire James Ferguson “Jimmie” Burns as an opera house on East Pikes Peak Avenue in 1912. It was turned into a movie theater in 1927. An elegant building with an Italian marble interior, it was torn down in 1973 and replaced by a drive-thru bank and a parking lot. How could such a thing happen?

“It was very complicated in the sense that the owners had no legal use of the building once it had closed down as an operating movie theater,” former city planner Tim Scanlon said.

The building did not meet modern building codes, and so, after 12 months, the bank that owned it lost the right to operate it without bringing it up to code. The bank claimed the building was woefully substandard and could not be updated for a reasonable cost, so it spent an “extravagant” amount tearing down the solid building, he said.

The citizen-led Landmarks Council of the Pikes Peak Region fought for the building, got it listed on the National Register of Historic Places and pushed the Colorado Springs City Council to acquire the building. When it came to the City Council to decide whether to ask voters if they wanted to save the building, two council members had to recuse themselves from the vote because they served as trustees with the bank, so the effort failed. There’s also some speculation that the arts community didn’t want the city to invest in the Burns Theatre because they were working on the new Pikes Peak Center for the Performing Arts, he said.

Second Antlers Hotel

This photograph from the early 1900s shows a view of the second Antlers Hotel with horse-drawn wagons on the street and St. Mary’s Church visible in the background. Carl Matthews Photograph Collection, courtesy of Pikes Peak Library District, 005-1984

The hotel was part of Brig. Gen. William Palmer’s vision for the town and greeted visitors as they left the train depot, according to the Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum. The Italian Renaissance-style building opened in 1901 and replaced an earlier hotel that burned down.

By the 1960s, it was old, tired, and with 12-foot ceilings, it cost a fortune to heat. It was also facing the wrong way. The owners wanted the front doors to greet the guests arriving by car on Cascade and Pikes Peak Avenue, Scanlon said. It was replaced by what is now called The Antlers, A Wyndham Hotel, in 1967.

The Cotton Club and buildings south of Colorado Avenue

Fannie Mae Duncan’s Cotton Club is seen in a 1970 photo by Norman Sams.

While it was not an architectural gem, The Cotton Club, owned by Fannie Mae Duncan, hosted Duke Ellington and Count Basie among other big names and drew an interracial crowd. Long after the building was torn down, Duncan was recognized for her work as an entrepreneur, philanthropist and community activist and was inducted into the Colorado Women’s Hall of Fame, among many other honors.

The club was one of numerous buildings in an area of downtown with many Black-owned businesses and homes that were torn down during the urban renewal movement that was sweeping the country in the 1960s and 1970s, said Professor John Harner with the University of Colorado Colorado Springs. At the time, businesses were fleeing downtowns and suburban malls were the hot new movement. Cities were facing blighted downtowns, and instead of offering business development programs as municipalities might today, they bulldozed whole neighborhoods, he said.

“At the time, people thought they were doing the right thing,” he said.

In Colorado Springs, the area bounded by Colorado Avenue on the north, Sahwatch Street to the west, Vermijo Avenue to the south and Nevada Avenue on the east was deemed a formal urban renewal area, Scanlon said. The Plaza of the Rockies, Alamo Corporate Center, city and county administration buildings and parking garages are some structures that now stand where historical buildings housed businesses such as tattoo parlors, taverns and second-hand shops, he said.

“We eliminated a tired portion of downtown and eliminated those uses that were deemed undesirable. We ended up with a pleasing urban environment,” Scanlon said.

However, the city’s use of eminent domain to take over private property for urban renewal in the 1970s created distaste for that tool, and that could help save more buildings today, he said.

The success of the urban renewal of the 1960s and 1970s is also in the eye of the beholder.

“We would be way better off with 25 little shops on every block than we would be with one giant megastructure where you can’t even walk in,” Harner said.

Little shops draw pedestrians in and make a block more inviting, whereas few people will keep walking beyond vast parking lots, he said.

Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum

The Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum, 215 S. Tejon St., occupies the beautiful granite building that was once the El Paso County Courthouse building. Courtesy of the Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum

While many buildings were lost, public and private efforts have helped save some of classic buildings, including the former El Paso County Courthouse, built as a symbol of the community’s wealth.

The landmark council helped save the former courthouse built in 1903 from demolition, in part, by arguing that if El Paso County wanted to demolish a building erected for the public in a public park, they should hold a vote. The vote never happened, but ultimately the city took over ownership of the building from the county.

In addition to a strong argument about public ownership, the idea to move the Pioneers Museum into the building also popped up and that was key, Scanlon said. Often the hardest part about saving a historic structure is finding a new use for the building, he said.

Lowell School

The Lowell School was covered with scaffolding during its remodel on Wednesday Feb. 7, 2001. Jay Janner/The Gazette

At one point in time the city’s largest school, it was boarded up in the 1980s, and concerned citizens feared it could be neglected beyond repair.

Scanlon recalled borrowing the keys from the owner and clearing a path through the building to give tours and stoke interest in the Richardsonian Romanesque style building constructed in 1891.

Ultimately, the Colorado Springs Housing Authority saved the day by putting together the financing to turn the building into offices, he said.

Cheyenne Building

The 1901 Cheyenne Building, which now houses Phantom Canyon Brewing Company, was named after Cheyenne Mountain and Chief Two Moons of the Cheyenne Indian Tribe. A stone carving of the chief watches over you as you enter and exit the building. (Mark Reis, The Gazette)

Now home to Phantom Canyon Brewing Company, the former railroad office building was going to be torn down for a bank’s new building. When those plans fell through, it was slated to become a parking lot in the 1990s until a well-known Colorado figure stepped in, Scanlon said.

Former Gov. John Hickenlooper bought and saved the building from redevelopment, transforming it into a brew pub as he had other old buildings. The city’s application of its historic preservation ordinance bought Hickenlooper 90 days to act, he said. The ordinance, even now, can’t stop demolition, it can only delay it, he said.

At one point the project also hit a snag and ran short of money. Contractors had to be convinced to take shares in the building as payment, Scanlon said.

Saving history for the future

Scanlon believes there is a wider understanding and appreciation for historic buildings that could help save more of them into the future.

Private lenders in the 1950s through the 1970s were much more comfortable with new structures because rehabilitation presents so much uncertainty and quite a bit of contingency money is needed. Now historical preservation is much more of an industry, lenders are more comfortable with it and more professionals have expertise in saving the structures, he said.

That’s key, because most preservation is done by private companies, he said.

Historical buildings could be safer in the future, in part because cities and business owners have found they can drive tourism and interest from those coming downtown for the restaurants and entertainment, Harner said.

“It pays off in the cultural capital you create. The place you preserve will really have some character, some originality,” he said.

This content was originally published here.