Regional books of note for August:

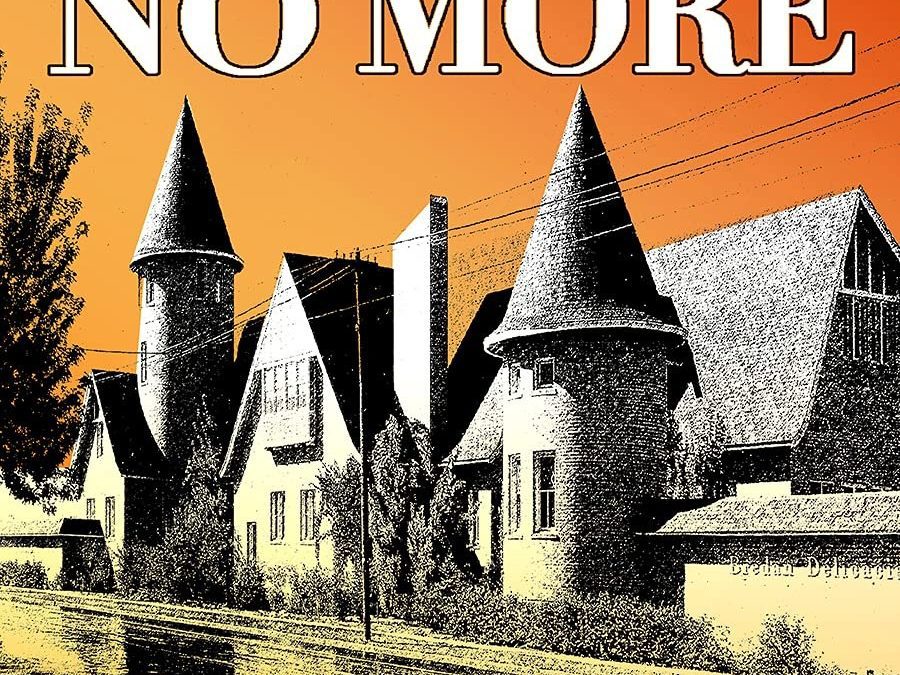

“The Denver That Is No More,” by Phil Goodstein (New Social Publications)

Nobody knows Denver architecture better than social historian Phil Goodstein. His latest, “The Denver That Is No More,” is a lament for all of us who resent the destruction of some of the city’s most memorable buildings. Think the Denver Club, LaVeta Place (owned by Augusta Tabor), the Breden Creamery, the Mining Exchange Building, the Tabor Grand Opera House, the Denver Arch, the Moffat and Kountz mansions, and on and on..

Buildings were torn down all through Denver’s history, of course. After all, there is virtually nothing left of the city’s first structures. But the real wave of destruction began after World War II. There was “an intense dislike of the Mile Hi City as it was,” Goodstein writes. “Anything old … was bad and a sign of the community’s cowtown past. Sleek, modern highrises were necessary to show that Denver was the capital of the Rocky Mountain Empire.”

Real estate investors such as William Zeckendorf “mocked Denver as a community that time had forgotten,” Goodstein says. As a result, the city turned its back on its Victorian heritage and replaced historic structures with mid-century modern buildings (many torn down only a generation later).

Just how much was lost is evident in “The Denver That is No More.” Goodstein includes photographs of dozens of lost buildings along with brief histories and occasional acerbic comments that he’s known for. The destruction of landmarks, he concludes, “reflects the constant evolution of the community and the values of its residents.”

“Jim Bridger: Trailblazer of the American West,” by Jerry Enzler (University of Oklahoma)

Jim Bridger “is often viewed as America’s greatest frontier scout of his era,” writes author Jerry Enzler. “His knowledge of the West was uncanny, and his frontier survival skills were unparalleled. He could read the land at a moment’s glance and recall thousands of miles of past trails in an encyclopedic recital. His contributions to Western exploration and history are enormous, though the details are often forgotten today.”

Enzler rectifies that with this definitive biography of the mountain man, who was the first white man to discover the Great Salt Lake; who aided hundreds of immigrants; and whose work as a U.S. Army scout helped settle the West. Indeed, if Army officials had followed Bridger’s advice to use the Bridger Trail instead of the Bozeman Trail, they might have saved dozens of lives, both white and Indian.

Bridger went West at the age of 18 as a trapper. Later, he established Fort Bridger on the immigrant trail. Enzler debunks the tale that Bridger delayed travelers, including the Donner party, by directing them to the Fort Bridger route. That idea “is not consistent with his record of prudence and honesty,” he writes.

Bridger survived numerous Indian attacks and confrontations with wild animals, but in the end it was a mule that almost did him in and made his last days painful.

“Where the Truth Lies,” by Anna Bailey (Atria)

If Peyton Place were resurrected, it might well be the Colorado town of Whistling Ridge. It seems that everybody there is a killer, a thief, a homophobe, an arsonist, a xenophobe or a troublemaker in general. Not to mention that each of the residents has a secret.

Abigail Blake, a high school girl, disappears from a party. At first, she is thought to be a runaway, but when Abi’s blood-stained sweater is found, the police suspect foul play. Abi’s best friend, Emma, who failed to stop her friend from going off into the woods to meet someone, is filled with guilt. She sets out to find what happened to Abi.

The missing girl’s family is dysfunctional, to say the least. The father is brutal, the mother has checked out. A brother is conflicted about being gay and another is crippled because his father threw him down the stairs.

Emma, whose own father has disappeared, turns for help to Hunter. His wealthy father is a bigot — and perhaps a killer. The two find Abi’s Chapstick in a drawer in his office. Then there is the self-righteous minister, who stirs up trouble, and a Romanian motorcycle rider, who befriends Emma and plies her with booze.

The town is a teakettle waiting to boil over, and when it does, the result is violence and exposure of just about everybody.

(Note: In 2018, English author Anna Bailey spent a stint as a Starbuck’s barista in an unnamed Colorado mountain town. One hopes “Where the Truth Lies” is not based on her experiences there.)

“Colorado and the Silver Crash,” by John F. Steinle (History Press)

The Silver Crash of 1893, along with a nationwide panic, were devastating for Colorado. The price of silver plunged to 62 cents per ounce. Some 435 mines shut down, and stores were shuttered in silver towns such as Leadville and Creede and even Denver. By the end of the year, 377 businesses had failed, and 45,000 were unemployed. The state was in crisis.

Panicked Coloradans elected populist Davis Waite as governor and embraced evangelist Francis Schlatter as a messiah who would lead them to better times.

In this heavily researched and detailed account, Arvada author John F. Steinle combines Colorado’s situation with the panic of 1893, which led to widespread unemployment nationally and the rise of the populist movement. It culminated in the nomination of William Jennings Bryan as presidential candidate.

This content was originally published here.