If you were to ask any of the 1 million Americans living with multiple sclerosis, they’d probably say their disease started with changes so small they almost didn’t notice them: a wobbly step, a weakening grip, sight going soft around the edges. But MRI scans of their brains — dotted with ghostly white scars — would tell a different story.

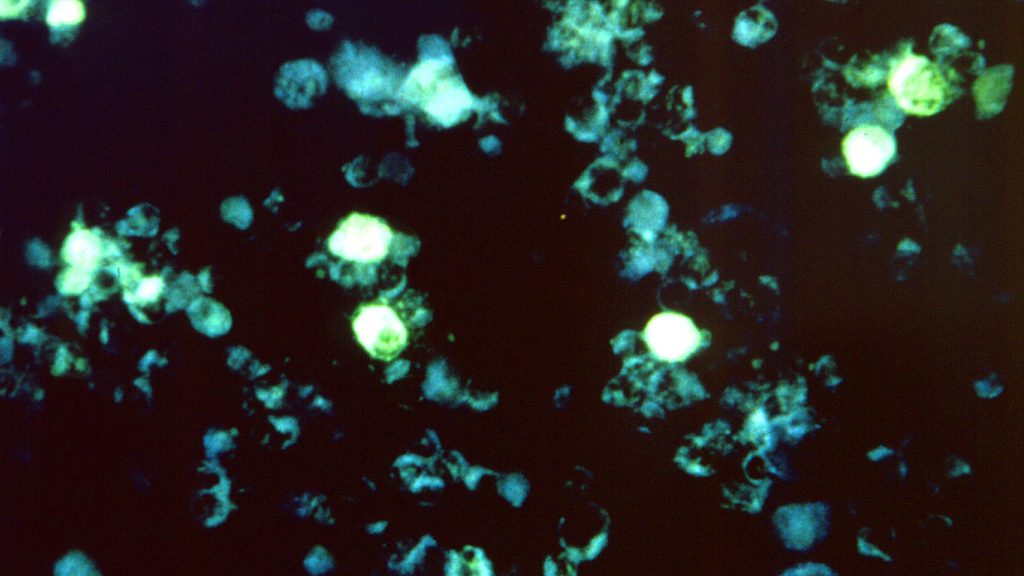

Those scars are signs of inflammation dating back multiple years. Each spot represents a dead zone filled with mangled remains of thousands, sometimes millions, of neurons. Like city blocks going dark during a power outage, these cells blinked out one by one after an immune storm stripped off the insulating myelin sheath that helps them send and receive electrical signals. But what triggers the immune system to turn on itself is still a mystery.

Now researchers have found strong evidence that it’s an infection, specifically the Epstein-Barr virus, best known for causing mononucleosis. In a large cohort of military service members followed over many years, infection with Epstein-Barr increased the likelihood of developing multiple sclerosis, or MS, by more than 32-fold, a team of scientists led by Harvard University’s Neuroepidemiology Research Group reported in the journal Science on Thursday.

Sign up for The Readout

Your daily guide to what’s happening in biotech.

More than a decade ago, his Harvard colleague, epidemiologist Alberto Ascherio had a hunch that the answer to what initiates MS might be frozen somewhere on the campus of the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research in Silver Spring, Md. Since 1985, scientists there have been collecting, screening, and storing (at 30 degrees Celsius) blood drawn from every member of the U.S. military every few years. With more than 62 million samples from over 10 million active and reserve duty members, the Department of Defense Serum Repository is the largest collection of its kind in the world.

advertisement

For biomedical researchers, the Serum Repository is their Hubble Telescope. It allows them to look not just deep into people’s bodies, but also back in time, to moments before the diseases they’re interested in took hold. That’s particularly important for MS, because it’s most often diagnosed in people in their 20s and 30s. In order to capture people prior to disease onset, you have to start sampling when they’re in their teens — like, say, when most military recruits sign up for service.

Brain inflammation is a not-uncommon side effect of viral infections — something the millions of people with long Covid are living testament to. In the early 2000s, Ascherio and others had found clues that the triggering agent for MS might be Epstein-Barr, or EBV, a particularly ubiquitous member of the herpesvirus family. The virus had been found in the demyelinated death zones of MS patients. And people with elevated levels of antibodies against EBV were more likely to be diagnosed with MS. To prove one caused the other, Ascherio, a co-author of the new paper, turned to the “experiment of nature” taking place at the Serum Repository.

Physicians who treat patients with multiple sclerosis and study the disease agreed that the work showed convincingly that EBV is both necessary for and precedes the diagnosis of MS. “This is a very intriguing article that extends our understanding of the role of EBV in MS development,” John Corboy, a neurologist and co-director of the Rocky Mountain MS Center at the University of Colorado, told STAT via email.

But, he said, it’s still too soon to say the virus alone is sufficient to cause MS. For example, the study does not explain why only a tiny minority of those infected with EBV develop MS. “It leaves many questions about pathogenesis unanswered,” Corboy wrote.

What the study really adds is showing in a time-resolved way the sequence of events leading up to an MS diagnosis, said Michael Wilson, a neurologist at the University of California, San Francisco, who specializes in poorly understood neuroinflammatory disorders.

The Harvard team didn’t just look for signs of the EBV virus itself or antibodies against it. They also went fishing for something called neurofilament light chain, or NfL. When under attack, neurons shed these threadlike pieces of themselves, and some of them wash into the cerebrospinal fluid and out into the bloodstream. Studies have shown that a rise in NfL levels precedes onset of MS by a couple of years. The new research found this marker of neurodegeneration didn’t increase until after infection. That argues against reverse pathology — where MS impacts the immune system to make it more susceptible to EBV infection.

“That lends this study additional weight,” said Wilson. “Not only were soldiers not diagnosed with MS at the beginning of the study, but their NfL levels were also negligible, so they probably didn’t have a case of MS smoldering under the radar.”

The study doesn’t explain how exactly EBV might trigger multiple sclerosis. Other research groups have speculated that the virus might carry proteins that resemble myelin, a case of molecular mimicry that could trigger an autoimmune reaction. Others have proposed that because EBV often takes up long-term residency in B cells, the latent infection may somehow transform these immune cells, making them pathogenic.

“It’s long been a theory that MS is a multifactorial disease,” said Wilson. Studies have shown that certain genes can heighten the risk of developing it. So can not getting enough vitamin D. Combined with an environmental exposure, like a viral infection, these factors might be enough to trigger the disease. “EBV probably isn’t the whole story, but this study helps show it’s clearly part of it. The exciting thing is that it’s a modifiable part of the story.”

We’re all stuck with the DNA we inherited from our parents. But EBV is a virus, so our immune systems can be trained to prevent it from infecting us. Currently there is no vaccine against EBV; efforts to develop one have historically been hindered by technical hurdles and lack of investment because the virus isn’t initially life-threatening. But studies like this suggest we should be pushing harder on developing a vaccine against EBV, said Wilson. Besides MS, the virus has also been linked to a variety of cancers and other autoimmune diseases such as lupus.

“Understanding the detailed mechanism of how EBV triggers MS is more of an academic question,” said Wilson. “For a public vaccination campaign, we just have to show that it reduces cases of MS, even if we don’t understand exactly how it’s happening.”

There are precedents for such a campaign. In 2006, regulators approved a vaccine to prevent spread of four strains of human papillomavirus, or HPV, which raise risks of developing cervical cancers that kill thousands of women in the U.S. each year. Although Americans were slow to get immunized, uptake in the U.K. was sky-high. A recent analysis found the vaccines have already nearly eliminated cervical cancer in young women there.

“If EBV is causing MS then this could shift the focus of research into trying to find a cure for MS as well as motivate vaccine development,” said Bjorevik. The study might also shift research priorities for other neurological conditions. For years, scientists have found evidence that Alzheimer’s disease might be driven by inflammation triggered by viral infections, including other herpes viruses. But these outsiders’ research has repeatedly been met with ridicule, their projects left unfunded and their hypotheses unexplored.

“Our findings are very specific for MS, but we expect it may spark interest in reexamining infectious causes of other diseases,” said Bjorevik.

This content was originally published here.