It’s impossible to tout the valiant efforts of one Denver cultural organization to keep art thriving during the great coronavirus shutdown of 2020 without mentioning a few others for context.

Like the Kirkland Museum’s virtual, 360-degree tour, which popped up on its website offering stay-at-homers a fun and free excursion through its permanent galleries; or Walker Fine Arts’ quickly assembled video trek around its current “Ghost Forest” installation by artist Melanie Walker; or the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver’s super-energized Instagram feed; or the Rocky Mountain College of Art and Design’s newly released, boredom-battling podcast “Remotely Creative.”

Not everyone is stepping up — some top museums seem to be taking the time off just when we need them the most — but the groups and galleries that are going the extra mile are offering us badly needed distractions during dark times. Combine that with the efforts of funders — like the Bonfils-Stanton Foundation, Black Cube Nomadic Museum and RedLine arts center — to help out struggling artists with actual cash, and this is a moment Colorado culture can be proud of.

The Colorado Photographic Arts Center adds mightily to the mix, using the pandemic as an incentive to put its entire in-house collection online. CPAC’s just-released digital gallery is an easily accessible assemblage of images featuring some of the world’s most-respected photographers past and present, including Ansel Adams, Imogen Cunningham, Berenice Abbott and Philippe Halsman.

The collection, 180 artists deep, is high in quality and full of surprises — one of those Denver treasures that’s been hiding in plain sight for decades, that’s suddenly there for all to enjoy.

“We have a lot of work but no one really knows about it or how to access it,” said CPAC executive director Samantha Johnston.

The new archive is the culmination of CPAC’s four-year effort to organize and catalogue the photos it has amassed since its founding in 1963, when gifts from Adams, Halsman and Yousuf Karsh gave its permanent holdings a solid start.

The collection has grown over the years, at varying degrees, as the organization acquired what it could (mostly through donations since it doesn’t have a budget to buy new works). Many of the pieces came from artists who offered to leave behind samples of their work after CPAC featured them in one of the many exhibitions it has produced for the public.

Johnston and her team culled through hundreds of archival boxes and storage sleeves, examined their contents and then painstakingly rephotographed key works so they could go online in a digital format.

The project isn’t quite done; there’s still some key information missing from the online gallery and several works need to be uploaded and organized. But CPAC quickly put enough finishing touches on the presentation to get it up and running for people stuck in their houses during the present quarantine.

Johnston refers to it as a work-in-progress, but it’s more than that. It might take viewers a few clicks to find their way around, though once they do, the gallery provides a stunningly handsome journey through the history of photography reaching back to the mid-1800s.

It helps that photography, as an art form, presents well in digital formats. It would be impossible to create a gallery of painting or sculpture that has the same richness. Painting needs to be seen in person, so viewers can take in the subtleties of surface and the depth of color that artists instill in their work. A van Gogh, for example, loses its character online, where it is impossible to experience the globs and slathers of oil paint its creator built into his objects.

But photos are, by and large, made with a flat surface in mind, usually the paper or metal they are traditionally printed on. That has always been something of a limitation on the art form; photography, by its nature, can seem a little cold and mediated by the machines required to make it happen.

But in the digital age, it’s a plus. Two-dimensional computer screens are suitable platforms for photographs, which are two-dimensional by necessity. Digital images aren’t exact replicas of printed pictures, of course, but they can be distributed widely and authentically on the Internet.

That makes clicking through CPAC’s collection a credible and efficient art experience. Images like Adams’ 1963 “View East to the Great Plains From Cimarron, N.M.” or his 1937 “Mirror Lake” convey nearly all of the organic drama the photographer intended to capture in his grand, Western landscapes.

The photos in CPAC’s collection are sorted by photographer, and they are searchable by title and certain keywords (like “animals” or “cemeteries”), and they are often accompanied by text that explains something about the scenery or the artist’s career.

They don’t always have dates or exact locations or the names of subjects, which makes looking at vintage works something of a mystery. Portraits and streetscapes from the late 19th century and early 20th century are captivating, and revealing, though they can raise more questions than they answer.

The collection’s strength is in its variety and diversity. It covers a world of geography and a long list of social movements and political events, wars, protests, the faces of world leaders. But there are scores of casual moments in the lineup that convey how society has changed. The range is wide: Abbott’s “Changing New York,” for example, freezes Manhattan in the 1930s, back when horses still pulled milk coaches. Other images, such as Jamil Hellu’s 2012 portrait of a costumed superhero in San Francisco, mirror culture in the current age.

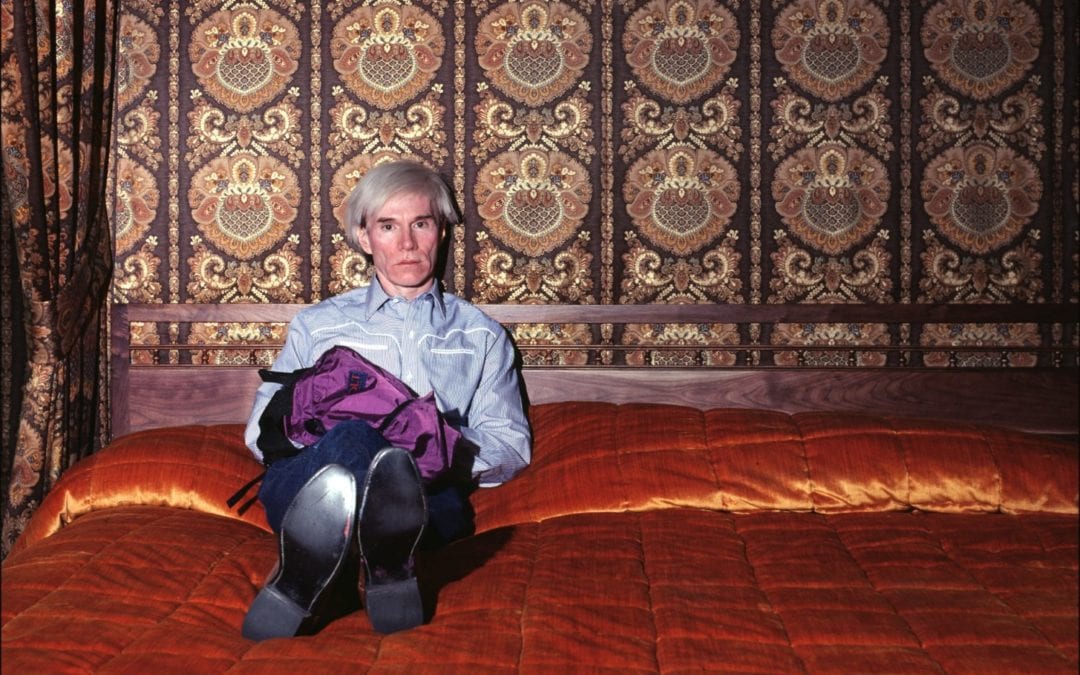

There are also a few oddball celebrity moments that keep things interesting, like John Bonath’s portrait of Andy Warhol from the 1980s, or Ken Heyman’s extreme close-up of Audrey Hepburn, probably from the 1960s.

Several photographers stand out and are worth spending time with, among them Edward R. Miller, who is represented with several mid-century shots taken around the globe; Peter Menzel, who made candid portraits of Boston street life in the 1970s; Vivian Keulards, who contributes two recent color portraits of children; and Ralph Morgan, who photographed notable figures from the 1920s and ’30s, including presidents Calvin Coolidge and Theodore Roosevelt.

Notably, there is a large amount of work by R. Ewing Stiffler, who was born in the late 1800s and lived much of his life in Colorado. His lush and romanticized pictorialist images of the state and beyond are nearly forgotten.

This collection gives folks a chance to rediscover his work, but also the products of scores of other artists, some famous, though most not. CPAC has always made its holdings available to researchers and students, but this new online archive takes something that’s generally been off-limits and “makes it something that’s usable” for the community, as Johnston puts it.

And it comes along at just the right time.

CPAC’s permanent collection can be viewed online at cpacphoto.org.

This content was originally published here.