If Debbie Wilmot could turn back time, the city of Lafayette would have scanned its computer network regularly. It would have hunted down and plugged holes that tempt cyber prowlers. And there would have been more training sessions to keep cybersecurity awareness high among the town’s 200 employees.

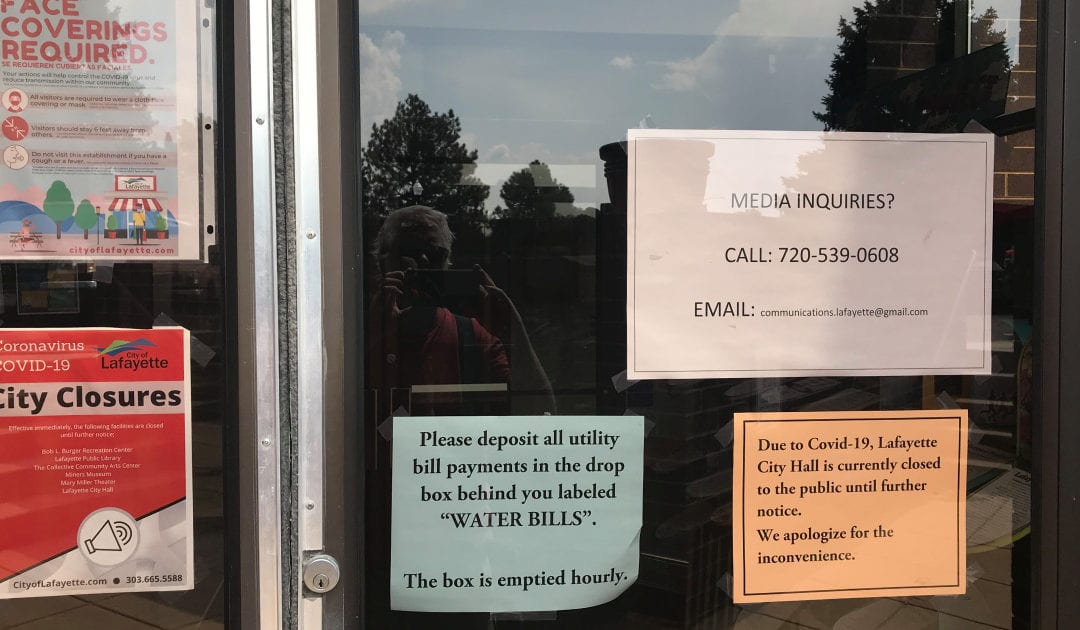

The town of about 30,000 people is now just another statistic in the world of cyber crime. Lafayette became yet another victim of a cyber attack late last month that hijacked computer files and resulted in a disruption to the city’s computer network, phone lines and email. To avoid further disruption, officials paid the ransom.

Colorado cyber attacks

Recent and notable database breaches and ransomware attacks on public facilities and organizations in Colorado.

“You’re never going to be in a place where you can eliminate 100% of the risk,” said Wilmot, a spokeswoman for the city. “That said, there’s definitely things you can do to make sure that you can recover things easily. … We’ll come out of the situation stronger, more productive and with our eyes open wider to be aware of what we need to do just to be more diligent of assessing our vulnerability.”

Lafayette is probably like a lot of towns in Colorado. It has a police department, a parks and rec department and a website. The city handles all sorts of financial transactions, from licenses and permits to court fines and water utility bills. And like most small towns, its small staff doesn’t include a dedicated cybersecurity professional.

As cyber attacks and data breaches have increased in the past several years, companies and organizations of all sizes are taking security more seriously and investing in tools, staff and training. But the added expenses often is difficult to justify to a city council or school board until after an attack.

“Cities, counties and school districts are not well-equipped to address a breach of any kind – data or security,” Eva Velasquez, president and CEO of the Identity Theft Resource Center, which tracks breaches and ransomware incidents globally. “They generally lack the resources to have the latest tools and they rarely have the latest generation of tech, which means as it ages, it becomes more vulnerable to attack.”

Small and rural municipalities may not even know what they need or what to ask for, said Bob Bowles, director for the Center for Information Assurance Studies at Regis University in Denver. And all of this has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, as employees were sent home, where security can be more lax.

“Investment is probably the major setback,” Bowles said. “But particularly now with COVID-19 where you’ve got a lot of companies and cities and governments that probably have had to reduce staff and are working remotely. If they didn’t have a good security policy to begin with, then all of a sudden now you just injected another type of risk. Your whole work environment has changed.”

Cyber help is near

Good thing Lafayette has good neighbors. Last Monday, Lafayette made an emergency declaration, which allowed it to get help from the state, the federal government and its neighbors like Boulder County Emergency Management.

But its neighbors stepped up before an emergency was declared. Members of the county’s emergency management showed up within days of the July 27 attack to pitch in, as did the state’s IT office, which sent two staff members to assist, said Wilmot, whose city also reached out to cybersecurity specialist Rule4 in Boulder

“We had lots of wonderful help from our neighboring municipalities that were on site right away,” she said. “I felt like we had a lot of great guidance. They helped us create a plan of attack and organize how we’re (now) attempting to bring all of this back.”

Often, small towns just don’t even know where to start. That’s when Benjamin Edelen steps up. He’s the chief information security officer for the city of Boulder. He partners with security professionals at larger cities to lend their expertise and help smaller government employees get trained.

“We collaborate to mentor and bring up everybody in the local government space in Colorado, and share resources if we can help,” Edelen said.

Boulder may be a little unusual in that it has a cybersecurity team. It also had a lot to share. The city changed its digital policy a few years ago to focus on identity rather than on buildings. That way, an employee must prove their identity whether working from inside a city building or at home or out of the country.

It still relies on traditional security technology, like network monitoring, endpoint security and other vulnerability assessments. It also ramped up all of its security policies, requiring employees to use multi-factor authentication and 20-character passwords.

“Twenty characters is a huge password. But we decided to take that leap, because, again, in order for this to work, we have to know that it’s you. And then once we know that it’s you, we’re pretty darn confident that it’s OK,” Edelen said. “But hold on tight because we’re not done yet. I don’t want to declare victory here, but the city has had no major issues. We’ve seen a huge increase in phishing emails. We’ve seen plenty of dangerous scenarios crop up. But we haven’t had serious impacts on the organization.”

Having all those security features in place before the pandemic made him feel a little bit better about sending employees to work from home. He’s not so sure about neighboring towns and other local governments.

“But the fact of the matter is most cities and counties are taking on significantly more risk, bringing their employees’ home network into scope,” he said.

The state of Colorado also provides a lot of cybersecurity resources for any municipality or county that asks. But it’s all voluntary because of home-rule laws, which give control to the local municipality, said Micki Trost, with the state’s Department of Public Safety, which did help Lafayette, a home-rule city, during its ransomware attack.

But the challenged budgets local governments have is why Edelen steps up. By sharing his resources and knowledge with security employees in other cities, they’re able to step in when asked by smaller towns and governments. The Colorado Information Analysis Center is one group run out of the Department of Public Safety. It’s a Fusion Center, which the U.S. Department of Homeland Security established after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks to increase communication between state, local and federal sources on terrorism.

In return, participants learn valuable lessons from one another’s cyber experiences, like the 2018 ransomware attack at the Colorado Department of Transportation.

That started when a state employee with administrator privileges set up a temporary server to test out a new service but did not apply standard security controls to it.

Attackers found the unprotected server immediately, made 40,000 password guesses — the administrator access allowed unlimited failed logins — and infiltrated the system three days later. They locked files and demanded bitcoin for the key to CDOT’s files.

The recovery team was led by Debbi Blyth, the chief information security officer for the Governor’s Office of Information Technology. The state did not pay the ransom, but spent the next 31 days trying to stop the spread and recover files before proclaiming success. The cost for overtime pay, equipment and other services wound up being around $1.7 million.

Afterwards, Blyth was able to ask for a larger budget to fix many of the things on the state’s security to-do list that it had been unable to get enough funding for. The Office of Information Technology, which manages technology for 17 state agencies, installed new firewalls to track everything going in and out of state computer networks, required vendors to use two-factor authentication, and reduced the number of privileged administrator accounts to 50 from 500.

“Many of us got tremendous information from Debbi Blyth” at the state, said Edelen, with the city of Boulder. “That information totally changed our approach to protecting our groups. It helped us to lock down the loopholes that were used in the attack but it also gave us a sense of a new means of escalating our requests for aid. … They piloted this extraordinary idea that we use the emergency management infrastructure, the same infrastructure that is used to ask for surge capacity in a fire or a flood, to ask for assistance in a cybersecurity incident.”

The $45,000 Snatch ransom

City of Lafayette officials say they don’t know whether the ransomware was the result of employees working from home. They said perpetrators got into the city’s computer network either through phishing or brute force, meaning that the attackers just kept guessing passwords.

In the early hours of July 27, ransomware known as Snatch began locking computer files on the city network. The city shut down its network, which meant city emails and phone lines didn’t work. Alternatives were set up and were still being used as of the weekend.

Snatch showed up on the radar of Webroot, the Broomfield-based cybersecurity company that develops tools to combat malware and other cyber threats, back in April 2019. The malicious software attacks Windows machines by putting them into safe mode, where most software, including security software, doesn’t run, said Marcus Moreno, Webroot’s manager of threat research.

Snatch isn’t typically the result of a successful phishing attempt, but rather an unplugged hole in the computer network that might have just been opened or sitting open for a while. It uses remote desktop protocol to attack and brute force to get inside a system. Proper security software could have blocked those multiple login attempts or notified the user of open ports. At a minimum, Moreno recommends people should back up their files.

“No security software is 100% foolproof. Things are going to get by. But you should always, always, always have that cushion so you can rely on your backups,” Moreno said, pointing to the small town of Colonie, N.Y., which had backed up its system and avoided a $400,000 ransomware demand. “Backing up your software isn’t necessarily that expensive. It all depends on the frequency and the amount of data you have. But I think it’s very necessary for any business or consumer out there that likes to store data.”

According to a statement from Lafayette, the city did have backups of the locked financial data. It also said personal credit-card information of residents wasn’t compromised. But to rebuild the locked files would have cost more than the $45,000 ransom so officials paid after a week without access to the city’s network.

“I can tell you that using taxpayer funds to pay a ransom was definitely not the direction the city wanted to take,” Mayor Jamie Harkins shared in a public video posted on Youtube. “… After a thorough examination of the situation and cost scenarios and considering the potential for lengthy inconvenience service outages for residents, we determined that obtaining the decryption tool far outweighs the cost and time to rebuild that in systems.”

Wilmot said the city had cybersecurity insurance with a deductible of $100,000. Additional recovery costs beyond the ransom will be applied to the insurance policy but may still have to come out of the city’s general fund.

The city now has the key to unlock the files, but the recovery process is expected to be slow and methodical, she said. Files have been unlocked, but are being cleaned and tested. She doesn’t know how long the process will take.

Many in the security industry, including federal law enforcement, advise against paying ransoms. There are many reasons — it financially supports criminals, they may not provide the right key and it only emboldens criminals to attack again.

“You shot yourself in the foot by not taking the means necessary to protect your data,” said Moreno, with Webroot. “(Unless it’s) a life-or-death situation and you need this document because it has some type of information that you need to save someone’s life, I can’t think of any reason why anybody should ever pay the ransom.”

But many still do, including Regis University, which found itself in a bind when ransomware attacked its network last August as students were returning to school. The school had cybersecurity insurance and decided to pay an undisclosed amount.

“We (as cybersecurity staff) did not have a say in that,” said Bowles, with Regis University, which offers cybersecurity degrees and often works with the state’s Office of Information Technology to share knowledge. “They basically looked at what was the welfare and what was in the best interest of the students so therefore that’s why they did.”

But if it were up to him, he wouldn’t have done it, he said.

“My opinion, which is Bobology, you never pay the ransom,” Bowles said. “In a normal circumstance, you don’t pay the ransom because what they do is they’ll come back and hit you again.”

Our articles are free to read, but not free to report

Support local journalism around the state.

Become a member of The Colorado Sun today!

$5/month

$20/month

$100/month

One-time Contribution

The latest from The Sun

This content was originally published here.