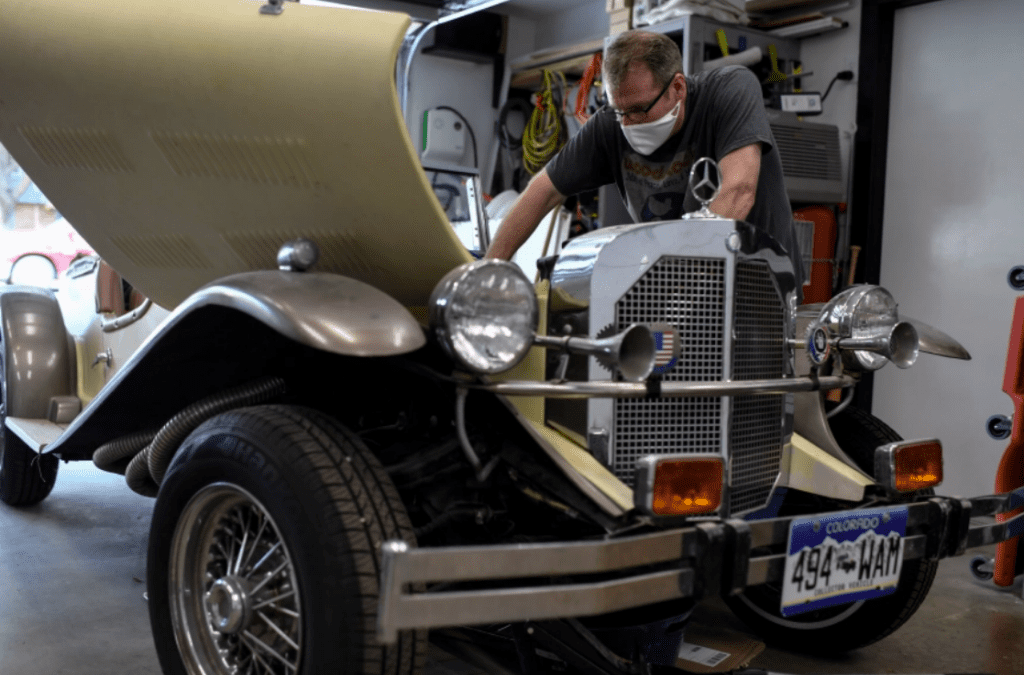

Boulder social studies teacher Peter Kingsley always thought he would leave education when he was ready.

It would be the day Kingsley, a teacher and coach at Southern Hills Middle School, showed up to work and couldn’t laugh alongside his students anymore.

After 25 years of teaching in the Boulder Valley School District, that day still had yet to come. But this summer, Kingsley decided to retire early rather than return to school under new conditions caused by the coronavirus.

Kingsley is one of many teachers who feel like the ongoing pandemic is forcing them to choose between their life and their livelihood. While it’s too soon to say if a significant number of educators will leave the field, they are certainly considering it.

In a mid-July survey conducted by the Denver Classroom Teachers Association, more than 75% of respondents said they were reluctant to return to an in-person learning environment and 8% said they’d resign if that’s how the school year started.

It wasn’t an easy decision for Kingsley to leave. But the 54-year-old has epilepsy and a brain condition that makes him predisposed to strokes, so he’s at an increased risk of severe illness should he catch COVID-19. The social studies and physical education teacher is also admittedly not great with computers and prefers to teach in front of a classroom. Virtual formats didn’t feel like a fit last spring.

Kingsley may have even put those considerations aside this fall had his father not passed away in July after a battle with cancer. After spending 22 days with him in hospice discussing life and death, Kingsley realized he’d rather cross a few more things off his bucket list than potentially put himself in harm’s way.

“I never in my wildest dreams envisioned that I would make a phone call a month before school and say I’m retiring. That’s not the type of person that I am, but my hand is really forced at this time,” said Kingsley.

The Colorado educators interviewed for this story do not want to leave teaching, primarily because they’re passionate about the work. Some have invested their entire careers in the profession and feel stuck because their skills don’t translate well to many other industries. The current job market also isn’t exactly ripe with opportunities, they said.

But the risks associated with interacting with dozens of students indoors each day and a lack of cohesive guidance about the coming semester has only compounded broader issues within the education system. Each day the calendar flips closer to the start of the school year, the decision about whether to stay or go becomes more agonizing.

“It’s not so much that there’s been one event or one trigger that has made me reconsider teaching as a career,” said Cameron Hays, a Denver social studies teacher. Hays plans to teach during the 2020-2021 school year, but his long-term ambitions of moving into school administration and education policy are now uncertain.

“It’s just the holistic element of the demonization of teachers, the uncertainty of what (school) will look like, not having a coherent plan, the government not really supporting parents who need to stay home and watch their kids,” he said. “It all just adds up, and it’s not a high-paid career already. I don’t know how much this is worth.”

Teaching was tough pre-pandemic

Trends in the number of educators entering and staying in the field were troubling before the pandemic, said Kathy Schultz, dean of the School of Education at the University of Colorado Boulder. Universities nationwide are not only seeing a decline in the number of students pursuing teacher preparation programs, but many who do end up teaching don’t stay as long as they used to, Schultz said.

“Teachers, rather than seeing teaching as a 20-year career, are seeing it as a 2- or 3-year career and moving on to something else,” Schultz said.

Salaries provide little incentive to stick around. In 2019, public school teachers in Colorado made $57,746 on average, according to the Department of Education, up about 17% from $49,181 in 2009. Because of the high cost of living, a 2019 Zillow study estimated mid-career Denver teachers spend more than half of their salary on rent.

“When people talk about the teacher shortage often they just focus on how many teachers are entering teaching. But it’s equally problematic that teachers are leaving early,” said Schultz. “With COVID and with what teachers perceive as worsening conditions for their teaching, I think it’s a fairly worrisome trend that districts and schools and really the whole country needs to take very seriously.”

Part of the reason teachers aren’t sticking with the profession long term is because of how the job has changed, according to Schultz. Teaching has become increasingly regulated, offering fewer opportunities for educators to be creative with a curriculum and thereby making them less intellectually excited about it, she said.

Teachers are also under more pressure than ever to adopt roles beyond simply educating. They act as caretakers, making sure kids have access to food and mental health services. They serve as counselor when students need help beyond academics. They prepare for the possibility that their school will be infiltrated by someone with a gun. And now with COVID-19, they’ll be expected to enforce mask policies, sanitize classrooms and tailor their lessons for virtual platforms and in-person classes, depending on how their school plans to welcome students back in the fall.

“I don’t feel like society recognizes what teachers do, how we do it,” said Hays. “It’s never been a career where there’s a lot of respect all around. A lot of people feel like they went to school, so they know what teaching is all about.”

Schultz said the expectations are unfair, especially as school budgets are continually shrinking.

“Cities and states have less and less money to support teachers, and so there are fewer supports for teachers and students in schools,” she said. “You talk to teachers, they feel like they’re being thrown into an unsafe situation and there isn’t regard for their safety and health.”

Not worth the risks

Michele Morales, a fifth-grade teacher at Joe Shoemaker School in Denver, doesn’t think many of the new protocols outlined for an in-person return go far enough to keep teachers and students safe. She was relieved when Denver Public Schools announced it would extend remote learning through at least mid-October but remains cautious about what might happen thereafter.

As a single parent of two, Morales understands the allure of sending kids back to school. However, parents don’t understand that many of the beneficial aspects are going to be hindered by procedural changes due to COVID-19, she said.

Should DPS decide to return to in-person learning before Morales feels comfortable, she said, resigning isn’t off the table.

“I’m my children’s only parent. That is the most important role in my life,” Morales said. “I love my job and I’m really good at my job, but it’s not worth my actual life. … I will not be part of a system that says even one child or one adult illness or death is OK.”

With just weeks until the start of the year, Kathy Derry, a substitute teacher in Gunnison Watershed School District, said there are too many unanswered questions for her to return this semester.

Gunnison County Public Health’s Coronameter indicates conditions there are safe for a 100% return to brick-and mortar-schooling. If a staff member has a presumed positive or confirmed case of COVID, the district’s plan says that person cannot return to school until at least 10 days after first showing symptoms, at least three days without a fever and marked improvements in symptoms.

Details and duties for substitutes, however, are not addressed in the plan, and administrators haven’t communicated them to Derry.

“As substitutes, you don’t get paid very much. You don’t have any health insurance,” said Derry, adding she makes about $100 a day before taxes. “So my question is, are they going to provide health insurance? What is the plan for substitutes and is there any financial incentive?”

Now that her 87-year-old father-in-law is planning to move into her home, Derry is foregoing teaching this fall so she doesn’t accidentally put him at risk of contracting the virus. She feels lucky to have that choice when others don’t.

Adam Francis, a science teacher at Frederick High School, welcomed the news this week that St. Vrain Valley School District will do remote learning only at least through the end of September. Long term, though, he feels “handcuffed” weighing the choice between his personal safety and losing his income.

The prospect of changing careers is daunting.

“I don’t know what I would do,” the 46-year-old said. “In any career, if you decide in your mid-40s you’d like to do something different, you’re losing years of experience, you’re a less attractive candidate. It’s a skill set that doesn’t necessarily easily translate to other professions.”

Theresa McGuire, an art teacher at Lake Middle School in Denver, agreed. After 20 years teaching, McGuire doesn’t know what kind of career move she would make. She only knows this year could potentially be her last.

“Risking my life and possibly bringing this home to my family and seeing them sick and suffer is not what I signed up for,” she said.

This content was originally published here.