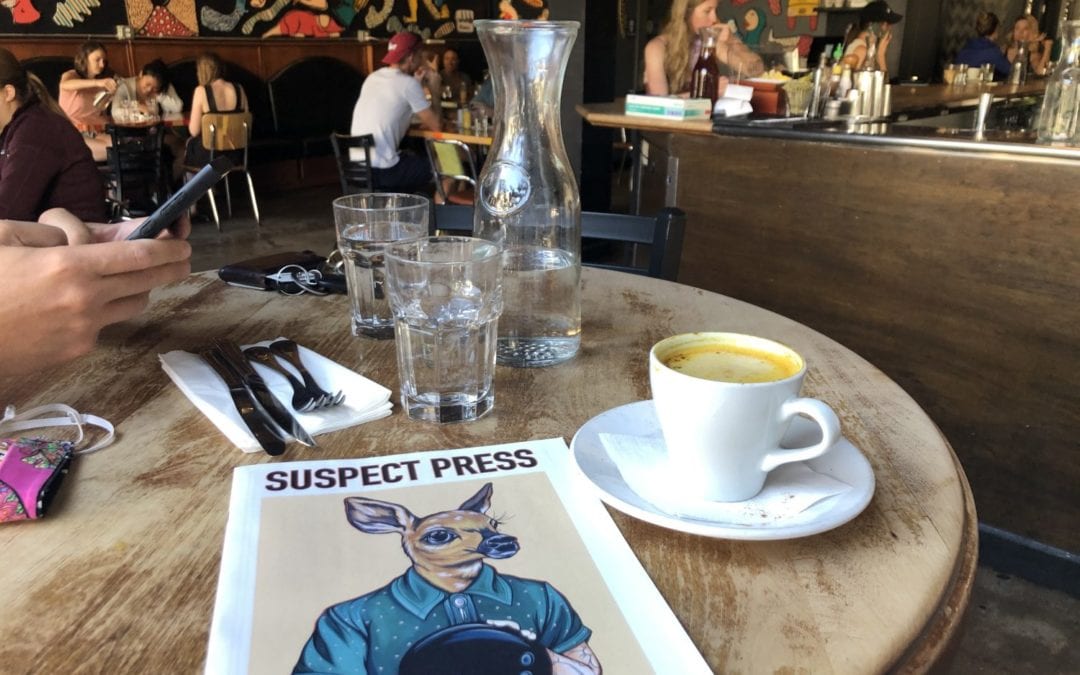

The final issue of Suspect Press, photographed at City O’ City in Denver. (Beth Rankin, The Denver Post)The website for Suspect Press, a seven-year-old Denver literary and art magazine, confronts readers with a stark yet familiar proclamation.

“PRINT’S NOT DEAD,” it states just under its digital masthead, and in relation to its Summer 2020 issue — the magazine’s 26th overall.

Just beneath that, however, is a letter from editor-in-chief Amanda E.K.

“We all know nothing lasts forever — especially not in 2020 — and we at Suspect Press have made the decision, after 7 years strong, to go another direction,” she wrote. “This is the last issue you’ll hold of this version of the magazine before we go into hiatus. Then, when the time is right, our art director Lonnie MF Allen will introduce you to a new draft of Suspect.”

But it wasn’t just the pandemic that did it in.

“We knew already a year ago that our Meow Wolf contract was running out,” E.K. said over the phone. “We were like, ‘What’s going to come next? We could look for grants and investors, keep talking with Meow Wolf, or become a nonprofit.’ We already knew we were going to be struggling in 2020.”

In fact, the $125,000 grant from Meow Wolf — Santa Fe’s buzzy art-and-entertainment company that’s planning to open a Denver location next year — was originally set to run out this week. But having laid off half its staff earlier this year, Meow Wolf ended that contract two months early, E.K. said.

“We used their money to help build our book-publishing business, pay salaries and make this a full-time gig,” E.K. said. “That was extremely exciting.”

With an average, pre-coronavirus distribution of 5,000 copies at more than 300 metro-area locations, Suspect Press looked like a success story amid Colorado’s boom-and-bust publishing scene. Even with the decline of traditional media and the rise of multiple digital-news startups, the Front Range has always boasted a panoply of free, arts-and-culture-focused print magazines that can be picked up at book stores, coffee shops, dispensaries, liquor stores, music venues, bars and restaurants.

Suspect Press editor-in-chief Amanda E.K., left, and former editor Josiah Hesse in a photo shoot for Out Front Colorado — another free, independent print magazine in the metro area. (Veronica L. Holyfield, provided by Suspect Press)”Cool, free, arty zines and publications like that — they’re always a struggle,” said Patricia Calhoun, founder and editor of Westword, Denver’s alternative newsweekly that often sits near these free, local magazines. “They’re usually labors of love. People do things like Suspect Press because they believe in them, not because they’re going to make money.”

Some independent magazines do, however. While Suspect Press was a black-and-white newsprint publication, Denver’s monthly magazine Birdy is a sturdy, full-color art concern that has recently expanded to Los Angeles. The Rooster, a college-aiming magazine based in Longmont, runs more like a national glossy, with copious ads, happy hour guides and other millennial-targeting content.

Edible, which expanded from Colorado Springs to Boulder, Denver and Fort Collins earlier this year, tells stories of the people behind the food we eat. The Marquee, a free, Boulder-based print magazine distributed to more than 30 locations since 2013, has filled in the gap of major-market publications’ coverage since investments in music journalism have dropped in recent years.

The Rooster, a free monthly magazine that’s delivered at drop spots around the Front Range, bills itself as “a magazine that allows you to relax and fully engross yourself in a humorous and provocative editorial journey that won’t drain, but enlighten and excite.” (Beth Rankin, The Denver Post)All of these magazines have wildly different revenue models, goals and character, their publishers are quick to point out. But what they share goes beyond their free-to-take print models.

Plummeting or nonexistent ad revenue, hobbled distribution and overlapping national crises have forced them to consider what these labors of love are really worth, and how long they can be sustained. Owing to their print focus, most of the aforementioned titles had little to no online presence before the pandemic. They’re now scrambling to beef it up amid the overall trend toward virtual life.

That makes free, local, indie print magazines even more meaningful, publishers say, particularly as otherwise mundane, face-to-face experiences — from school lessons to doctor’s appointments — are increasingly conducted digitally. Despite the high costs of paper and ink, and the newly complicated business of distribution, there’s no substitute for the sense of community they encourage.

Ashley Kirkovich took over Edible Denver in January and released her first, retooled print issue in March. (Provided by Edible Denver)”Print is also a break from modern life,” said Simon Berger, founder of The Rooster. “It gives you a moment to step back from the overwhelming bombardment of technology and control your pace of information. There’s a novelty and nostalgia to it, but it really is a reprieve from your phone.”

The Rooster, which Berger launched in 2008, was one of Colorado’s first publications to openly accept medical-marijuana dispensary advertising (and, eventually, recreational ads) starting in 2010. While dollars from that green tide have seemingly lifted all publications in Colorado, Berger knew he had to diversify to keep his core print business afloat.

In addition to locking down big sponsors such as Kroenke Sports and AEG Presents, Berger and his staff launched Red Bird Creative Studios, an advertising agency, and are preparing to debut a digital happy-hour guide next month (yes, even during the pandemic).

But print is still a precarious place to be. The Rooster had to take three months off from publishing earlier this year after the pandemic hit as Berger figured out how to pay for it. With a normal complement of 75 to 100 advertisers, and average distribution of 60,000 free copies in 2,000 statewide locations, The Rooster had significant costs to cover.

Berger won’t say by how much his circulation or distribution has dropped since then. But when The Rooster came back in July with its first new print issue since the pandemic arrived, it was with renewed purpose — and austerity.

(Provided by Birdy Magazine)”We’re conserving cash, cutting our budget and not investing too heavily in anything outside the company,” he said. “And, of course, all of our events are on pause.”

As Berger also began to invest in his digital product, he watched subscriptions — which are typically low-to-nonexistent for free, locally distributed print magazines — jump from about 100 to 1,000.

“We’ve always wanted to create something people would pay for, but that they were lucky enough to get for free,” he said. “We want to be taken home, shared with friends, and displayed on your coffee table.”

Or the dinner table. The Colorado-based franchise of Edible, a free, printed food magazine with products in more than 70 U.S. and Canadian markets, had just relaunched in March when the pandemic hit.

“My timing was terrible,” said publisher Ashley Kirkovich, the former marketing director for Niman Ranch who had admired the magazine (formerly known as Edible Front Range) before purchasing it in January. “We’re a quarterly, so I felt like, for the sake of brand consistency, I really needed to be visible in the market.”

Without bars or restaurants for readers to visit (or for Edible to solicit advertising from), Kirkovich estimates the first issue’s distribution was down by about 60% over previous installments — though she admitted she doesn’t have many data points to compare it to. Her summer issue fared better, even considering that she curtailed the print run from 15,000 copies to 12,000 to adjust for decreased demand.

Jonny DeStefano and Krysti Joméi, co-founders and co-editors of Denver’s Birdy Magazine. (Provided by Birdy)For her fall issue, releasing Sept. 28, Kirkovich will bump Edible’s print run back up to 15,000 copies in anticipation of adding another 30 distribution outlets to Edible’s existing 50 or so. That’s impressive, considering she’s often felt too guilty to ask for advertising from her usual supporters.

“It feels so crummy to say, ‘I know you may not be in business when this comes out, but want to take out an ad?’ ” she said. “So I’ve definitely pivoted toward (advertising from) liquor and retail stores.”

Readership and ad dollars in some Edible markets has increased since March, Kirkovich said, based on calls with other publishers. She sees similar opportunity in serving Front Range foodies who have shifted from visiting every new restaurant that opens to baking, gardening and Instagramming their own kitchen experiments.

Kirkovich has also gotten creative, partnering with community-supported agriculture programs to add a free copy of Edible to the boxes of fresh produce delivered to farm-share buyers. But she refuses to go online-only.

“Call me old school, but at the end of the day, I bought a print magazine,” she said. “When digital fatigue sets in, people need something tangible to engage with when having a glass of wine.”

Also strongly committed to sticking around is Birdy, the monthly Denver art magazine that has benefited greatly from its artistic partnership with Devo founder and film composer Mark Mothersbaugh. Despite the trials of 2020, Birdy recently expanded its distribution to 140 locations in Los Angeles, with about 1,000 copies of each issue (total average monthly print run: 10,000) headed to potential new readers in that city.

Prior to the pandemic, Birdy was distributed to 300 or so locations along the Front Range, not including national and international subscriptions.

“We could not bail out on the most important moment in our lifetimes,” said Krysti Joméi, co-founder and co-editor of Birdy. “It sounds dramatic to say, but as a magazine, we’ve been through times that are just as hard as right now on our (business).”

As a result, Birdy has not skipped a single issue since March, despite ratcheting down its copies from March through May of this year to 3,000, about 70% off from its usual print run. Along with partner and co-founder Jonny DeStefano, Joméi has also seen Birdy’s web traffic skyrocket, despite her lack of past investment in it, even as they build up their print numbers again.

“We never had much of a website before this on purpose,” she said. “We were always, ‘We’re super punk-rock and analog, just like vinyl records!’ But since March, there’s been a real urgency to provide even more accessibility to our readers.”

In that, all of these publications continue a grand tradition of scrappy, DIY entrepreneurship that has defined the Front Range publishing scene for decades, said Westword founder and editor Calhoun, including now-defunct, nationally lauded titles such as Muse and Modern Drunkard.

“The fact that they’re independent means they generally don’t play well with others,” she said. “They often don’t have organizations behind them. Who’s got time for that? But you’ve got to have a patron, or grants, because publishing in print isn’t cheap.”

Whether or not institutions like D.I.N.K. — a.k.a. the Denver Independent Comics & Art Expo — return in the future (they took this year off, for obvious reasons), the scene will continue to exist regardless of economics. The passion inherent in independent publishing is stronger than market trends, publishers say.

“I’m sad that we’re losing this established platform that actually paid contributors,” Suspect Press’ E.K. said. “But I’m hoping that us fading away will inspire other young kids to come up in the scene, take what we did, and make it their own.”

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter, In The Know, to get entertainment news sent straight to your inbox.

This content was originally published here.