Rep. Joe Neguse grew up a Colorado kid, like most Colorado kids, with Red Rocks Amphitheatre as part of his cultural heritage.

A few weeks ago, he was out at the Denver city park touring the Civilian Conservation Corps site, the temporary home to about 200 men ages 18 to 25 who built the amphitheater. The New Deal program encompassed 3 million men nationwide to help get the country back on its feet from the Great Depression, the defining crisis of its time.

Colorado was home to 172 CCC camps, where 32,000 men, most of them locals, cleared out dead timber in the mountains and planted trees and shored up ditches on the Eastern Plains to reduce erosion and buttress Colorado against the Dust Bowl.

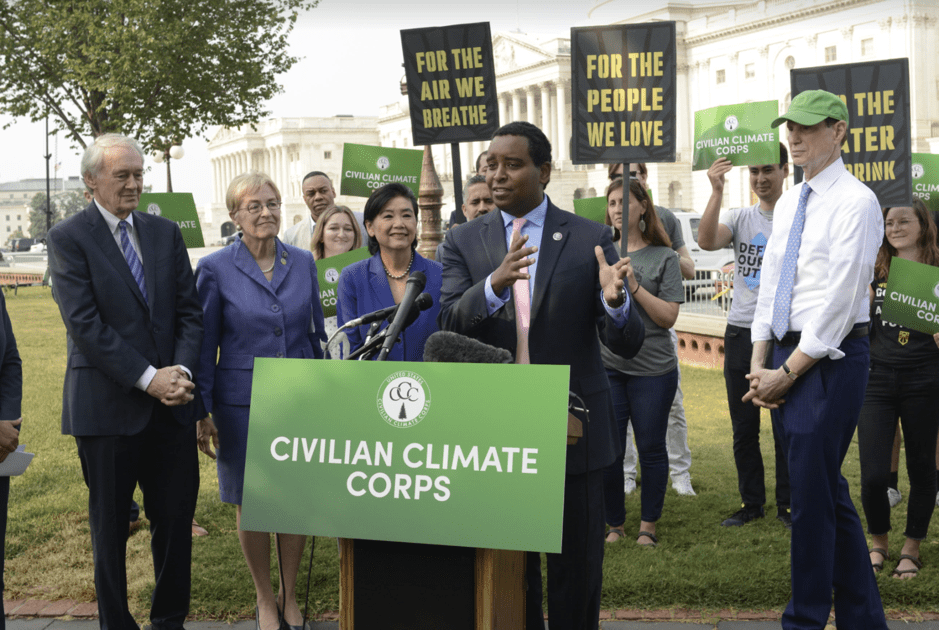

Neguse is now trying to legislate a new, diverse collection of young people called the 21st Century Civilian Climate Corps to dig out America again.

The $50 billion package includes $10 billion for workers, $40 billion for projects.

“Red Rocks is this behemoth presence — I mean, an architectural masterpiece,” Neguse told Colorado Politics in an interview. “It’s internationally known and every Coloradan treasures it.

“I think the scale of the work that needs to be done now is on par with the projects of the 1930s.”

Republicans, though hesitant to undercut dollars their communities need, have characterized the idea as a “job-killing boondoggle” aimed more at virtue signaling than planting trees.

The money is part of Democrats’ $3.5 trillion stimulus bill, which is expected to pass the House along party lines in the coming days.

The climate proposal faces a stiff challenge in the Senate. Democrats could pass it with a simple majority, given the tie-breaking vote of Vice President Kamala Harris. The path to the president’s desk, however, will still be one of attrition, not addition, with the Civilian Climate Corps primed to be whittled in partisan haggling.

The Climate Corps would put young people to work for $15 an hour restoring habitats wrecked by wildfires and floods, thinning forests, improving neighborhood parks or winterizing the homes of the elderly and poor, for example.

Neguse sits on the House Natural Resources Committee and chairs its subcommittee on national parks, forests and public lands.

“What it means to me is the biggest public investment in Colorado’s public lands and national forests, really, in a generation,” Neguse told Colorado Politics in an interview. “You’d have to go back to the way Red Rocks was built to appreciate something of that scale all across Colorado and all across the country. That’s what it means to me.”

His district is 52% public lands, and in 2020 was the site of the largest and second-largest fires in the state’s history, the Cameron Peak and East Troublesome fires, respectively.

Soon after President Joe Biden was sworn in, Neguse paid a visit to the Oval Office to talk over the idea. He pointed to the portrait of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt behind Biden above the fireplace and talked about the big ideas in FDR’s New Deal.

On Jan. 27, a week after he took office, Biden signed an executive order instructing the Department of Interior and the secretary of agriculture to develop a strategy to create the Civilian Climate Corps.

“The initiative shall aim to conserve and restore public lands and waters, bolster community resilience, increase reforestation, increase carbon sequestration in the agricultural sector, protect biodiversity, improve access to recreation, and address the changing climate,” the order stated.

Bringing it home

Especially in Colorado, the price tag for doing nothing is enormous, Neguse said.

“The sad part is obviously our outdoor recreation industry needs this,” he said. “That’s a big driver for Colorado’s economy and, in particular, my district. Our outdoor recreation is second to none, and yet we don’t invest nearly the resources that we should, especially relative to the need.”

What this would look like on the ground is also logistically hard to imagine in contemporary times.

“You’re talking about hundreds of thousands of folks working in our public lands in Larimer County, Grand County, Garfield County, down near the New Mexico and Utah borders,” Neguse explained enthusiastically.

“The southwestern portion of our state needs so much work; so do our national forests, taking out those wildfire fuels that we know are eventually going to generate the next megafire.”

Workers would plant trees to restore the forests and repair fire-ravaged watersheds that quench the thirst of flora, fauna and communities from Durango to Sterling.

A few weeks ago, Neguse went to Larimer County to see the aftermath of the Black Hollow flood in Poudre Canyon on July 20, killing three people and destroying six homes.

“I’ve never seen devastation like this from what should have been a small flash flood,” the congressman said. “But the speed of that water that came down off of the Cameron Peak fire burn scar was devastating. That’s the future we’re looking at.”

About the time he looked up from the flood damage, a helicopter flew over to drop mulch around a reservoir to buffer against erosion from the burned slopes.

“We’re now protecting our reservoir from polluting the water supply for Fort Collins, for Loveland, for Greeley, for almost a million people on the Northern Front Range,” Neguse said. “It just dawned on me as I was looking at all that, and I realized the scale of the crisis across this country. There’s so much that has to be done as a result of climate change. These natural disasters are here to stay, and they’re going to get worse — yeah, in Colorado — for years to come.”

How much money and workers Colorado gets will depend on how much Neguse and Sens. Michael Bennet and John Hickenlooper can preserve in the now-$50 billion ask in the final budget bill.

There might be shortage of money, but there won’t be a shortage of work, said Jessica Goad, the deputy director of Conservation Colorado, the state’s largest environmental advocacy group.

“The federal agencies like the Forest Service and National Park Service have a long list of projects that they need and want to support,” Goad said. “There’s a lack of clarity around that, but certainly this will be good for Colorado.

“A lot of the funding will go to the Forest Service to support wildfire mitigation projects, then it will provide people and help during natural disasters and help with water and habitat restoration projects. The focus, though, is on climate, not just conservation.”

Colorado model

Colorado isn’t waiting around.

The Mile High Youth Corps in Denver has been going for 28 years, creating paid public-service opportunities for people 17 to 24 years old.

The Denver-based corps claims that in 2019, its work helped conserve 3.1 million gallons of water and 408,557 kilowatts of electricity, while building 74 new low-income housing units through 101,537 hours of service in 22 Front Range and Eastern Plains counties.

In his State of the City address on July 26, Denver Mayor Michael Hancock lent the city’s backing for the conservation corps, pointing to Red Rocks Amphitheatre, to put young people to work restoring and safeguarding the city’s historical assets, but he also referenced climate.

“When we lift our heads, we can also see the opportunity, the need, to address climate change and create a new generation of clean-energy jobs,” Hancock said. “Another summer of wildfires makes this seem so obvious. It takes skilled labor to reduce emissions in our buildings, to build more solar, to install more electric-vehicle charging stations.

“More than just creating good-paying jobs, we’re going to make renewable electricity more accessible to our residents and businesses, especially for low-income residents.”

On Sept. 10, Neguse and Lt. Gov. Dianne Primavera announced the creation of the Colorado Climate Corps in partnership with AmeriCorps, Serve Colorado, the Colorado Interagency Climate Team, Great Outdoors Colorado and the Colorado Youth Corps Association.

AmeriCorps received about $1 billion from the American Rescue Plan last year, and Colorado is using its $1.7 million share for the corps, which Neguse hopes will become the national model.

The program, open to men and women 17½ years old or older, is expected bring 240 corps workers to 55 counties.

It makes sense that Colorado would lead the way, given the stakes. Colorado’s methane regulations were the model for those implemented nationwide by the Obama administration.

Voters in 1992 voters passed Great Outdoors Colorado, making it the first state to invest a portion of lottery proceeds into public lands. GOCO has since accounted for more than 5,300 conservation and recreation projects across the state.

Goad said Colorado and the nation have a chance to right three wrongs with the Neguse bill.

Half the Civilian Climate Corps will be people of color, which adds to the benefits of conserving public lands and fighting climate change, all the while putting people to work, she said.

“The new Civilian Climate Corps will be a huge help to address our triple crisis right now that we’re facing as a country, the economic crisis, the racial justice crisis and, importantly, the climate crisis,” Goad said. “Colorado will be much improved because of this program.”

Costly future

Part of the money in the 10-year plan would mean changes for energy gas development by increasing royalty rates and ending noncompetitive leasing for energy and mineral development, charging fees on offshore pipelines and idled wells, and eliminating royalty breaks, forcing companies to pay for annual inspection costs.

Lem Smith, the American Petroleum Institute’s vice president for federal relations, called the bill “a double-whammy of punitive policies to discourage U.S. energy development with new, targeted measures against the U.S. natural gas and oil industry.”

He said if the bill becomes law as written, it could lower domestic production “and boomerang the U.S. back to 1970s-era dependence upon foreign energy imports.”

Meanwhile, West Virginia Sen. Joe Manchin, a moderate Democrat, is a critical up-or-down vote on the floor, but he also chairs the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee. He is a self-professed ally of the legacy fuels industry, given his state is the nation’s fifth-leading energy producer, second in coal production and seventh in natural gas.

Other Democrats see addressing the climate and environment as an economic issue. Insurers are realistic about the costs of doing nothing.

The Swiss Re Institute, which advises global insurers on providing coverage to smaller insurance companies against major losses, predicted if industrialized nations stay on the course they are on, by 2050 the world’s gross domestic product could fall by 18%, or $23 trillion annually. By meeting the recommendations of the Paris Climate Accords, however, global GDP would decline 4%.

Impacts to agriculture and tourism hit close to home for Colorado, as two of the state’s three main economic drivers, joined, somewhat ironically, by fossil fuel development.

In an April report, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency said snowpack in the West has declined an average 19% since 1955. Numerous key measuring sites had declined more than 80%

“Diminishing snowpack can shorten the season for skiing and other forms of winter tourism and recreation,” the EPA warned. “It also enables subalpine fir and other high-altitude trees to grow at higher elevations. The upward movement of the tree line will shrink the extent of alpine tundra and fragment these ecosystems, possibly causing the loss of some species.”

The Colorado River’s average annual flow has declined almost 20% over the past century as more snow evaporates, according to the U.S. Geological Survey last year.

That’s all before considering the growth in the West and current 40 million Americans in seven states who depend on the Colorado River.

Up to half of the decline in the river’s average annual flow since 2000 has been driven by warmer temperatures, according to a consensus of recent studies.

Supporters and doubters

Support extends from the White House to Grand County.

In April, Winter Park Mayor Nick Kutrumbos wrote to the president in support of the Civilian Climate Corps concept.

“Given the historic need (to) address wildfire resilience, mitigation and public lands restoration, legislation such as the 21st Century Climate Conservation Act will not only take steps to address the climate crisis and address resiliency, but also put Americans back to work,” he wrote.

At least 30 Colorado mayors and county commissioners have endorsed the measure, along with other such supporters as the Boulder-based Outdoor Industry Association, Conservation Colorado, the Western Colorado Alliance and the Estes Park-based Rocky Mountain Conservancy.

Republicans offer up a smaller contingent of doubters and critics. Rep. Cliff Bentz, a Republican from Oregon, doubted people would do the work.

“Why would we think people are going to suddenly jump at doing really, really hard, dirty, dangerous work because we offer them $15 an hour?” he told The Associated Press on Sept. 9.

“That’s not going to happen.”

Arkansas Rep. Bruce Westerman, the ranking Republican on the House Natural Resources Committee, called it another New Deal program, saying “the idea that this is going to help land management is a false idea.”

Rep. Tom McClintock, a Republican from California, questioned Democrats in a Sept. 2 committee meeting about whether the corps was a political ploy, a “community organizing effort” to lure young people and communities to the left.

Immigration, too

Rep. Lauren Boebert of Rifle is one of 22 Republicans, including Rep. Doug Lamborn of Colorado Springs, on the 48-member House Natural Resources Committee, alongside Neguse.

In a Sept. 2 committee hearing on the bill, Boebert offered an amendment to divert 10% of the money in the bill to the “Biden border crisis” with Mexico. Nearly a quarter of the 1,950-mile U.S.-Mexico border is on U.S. public lands.

“As illegal border crossers seek to evade arrest, they travel across our federal lands,” she said, before her amendment was quashed by the Democratic majority.

Boebert alleged that between 2017 and 2020, during the Trump administration, park rangers apprehended 1,231 undocumented immigrants in the Stove Pipe Cactus National Monument along the border in Arizona.

The Defenders of Wildlife, however, agreed with Boebert in a 2006 report called “On the Line: The Impacts of Immigration Policy on Wildlife and Habitat in the Arizona Borderlands.”

“With increased immigration enforcement activities in nearby Yuma, Arizona, illegal migrant traffic has been pushed farther into Arizona’s delicate Sonoran desert, leaving the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument directly in the path of both large number of illegal immigrants and sometimes damaging enforcement activities of the Border Patrol,” the organization wrote in its report 15 years ago.

Democratic Rep. Raúl M. Grijalva of Arizona, who chairs the House committee, said the biggest environmental challenge facing public lands along the border has been “the wasteful, destructive and really ineffective border enforcement that’s been all the craze the last four years” under President Donald Trump.

He said Boebert didn’t understand “the real crisis at the border.”

He said Neguse’s bill was about fighting climate change and creating jobs, “not a political agenda of any kind.”

Republican Rep. Paul Gosar of Texas shot back, “Give me a break. Everything you’re talking about today is politically oriented.”

A week later, in a Sept. 9 hearing on the bill, Boebert tried in vain again to amend the bill, this time saying the work at The Presidio, a former military post that’s now a national park near the Golden Gate Bridge in House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s district, was “an egregious waste of taxpayer resources.” Boebert said the San Francisco park boasts of hosting environmental and social justice programs.

Neguse said his bill is about averting crisis, not picking partisan fights.

“I’m not gonna opine about how my colleagues, all my colleagues, think about this particular proposal,” Neguse said, when asked about using climate money for border enforcement. “I would just simply say that the money that we get, if this $50 billion becomes law, if this vision becomes a reality, the people in Garfield, Montrose, La Plata, Archuleta and Moffatt counties, all across the Western Slope, will be working with us and with many others to ensure that those funds support projects in their communities that are desperately needed.”

He called for an end to the political noise and a hard look at Colorado’s reality: wildfires, mudslides, erosion, dirty air.

“We gotta get prepared,” Neguse said. “We have got to get serious.”

This content was originally published here.