CHICAGO — The Center for COVID Control, an embattled chain of testing pop-ups, won’t reopen in Illinois amid an investigation from state authorities, the Illinois Attorney General’s Office announced Thursday night.

The company closed all its testing sites Jan. 14 as it faces federal and state investigations. It was set to reopen some locations Friday — but its leaders have agreed to stay closed in Illinois for the “foreseeable future” after the Illinois Attorney General’s Office contacted them, according to a news release from that agency.

The company is based out of suburban Rolling Meadows but has said it has 300 locations around the United States. It has been paid more than $124 million for testing from the federal government since the start of the pandemic and has processed more than 400,000 tests.

But the Center for COVID Control has come under intense scrutiny in recent weeks.

The Minnesota Attorney General’s Office filed a lawsuit against the company this week, the Illinois Attorney General’s Office and Illinois Department of Public Health are investigating it, the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid have cited its lab at the highest level of violations and other states have ordered the company to close testing sites.

“Complaints have ranged from testing results being delayed or not received at all, to results being provided to individuals who were never administered a test, to tests being stored improperly, and staff incorrectly using [personal protective equipment] and face masks,” Illinois Attorney General Kwame Raoul said in a statement. “Although the company voluntarily suspended operations, my office contacted company officials to demand that the Center for COVID Control immediately stop engaging in any fraudulent or deceptive conduct, particularly with respect to the delivery of testing results or billing.”

It’s not clear how long the company will keep testing sites closed. Raoul said its leaders agreed to “postpone the reopening of any pop-up testing locations in Illinois for the foreseeable future.”

Credit: Provided

Credit: ProvidedLast week, Block Club revealed an 81-page report from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services that detailed “deficiencies” and “non-compliance” at the lab used by the company, Doctors Clinical Lab. It was cited for “immediate jeopardy,” the most serious infraction, with inspectors noting the lab had made mistakes that led to wasting tens of thousands of PCR tests, workers not correctly processing rapid tests and the lab not properly storing test samples, among other problems.

Former employees of the Center for COVID Control have also told Block Club they were told to lie to customers, keep tests in unrefrigerated bags around the office and bill tests to the federal government, even when customers had private insurance.

And numerous people from across the United States have said they never got test results from the company, their results were badly delayed or their results didn’t make sense.

A spokesperson has denied employees’ allegations and said the company has been challenged by the latest surge in cases, but is now focused on training employees and complying with regulations.

“Center for COVID Control has acknowledged operational strains and customer service challenges largely beginning in late 2021 during the Omicron variant surge,” spokesperson Russ Keene said in an emailed statement Wednesday. “To address those emerging concerns company leaders voluntarily called for a seven-day national pause of local collection site operations to reset all operational aspects of the company and ensure accurate testing services continue to be made available to patients across the country.”

But former employees said the company struggled to keep up with tests and had issues for months before Omicron was first detected Nov. 26 in the United States.

While that confusion has unfolded, the leaders of the company have bought a $1.36 million home and have posted online about buying cars worth hundreds of thousands of dollars — including saying they bought a Ferrari that cost $3.7 million. Akbar Syed, who represents himself as a leader of the company, posted that he was able to buy luxury cars thanks to “covid money.”

Credit: Colin Boyle/Block Club Chicago

Credit: Colin Boyle/Block Club ChicagoInvestigations

CEO Aleya Siyaj registered the Center for COVID Control with the state in December 2020. Her husband, Syed, referred to himself as the “founding father” of the business on Facebook until recently, and has posted about the company on social media.

The Center for COVID Control only had a few sites in the spring, and it was able to get results to customers within a few days, former employees said.

But in the past few months, the company has grown to having hundreds of sites under its umbrella. The sites — some of which are independently owned, and some of which Syed has said he owns — promised free COVID-19 tests, with workers collecting PCR and rapid test samples from people who came in.

The PCR samples were sent to be tested at the Center for COVID Control’s lab, named Doctors Clinical Lab. The company headquarters and lab were in the same northwest suburban Rolling Meadows strip of offices.

As more testing locations opened and samples poured in to be processed, problems stacked up, former employees said.

Now, the company and its lab are facing various investigations.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has cited the lab at the highest level. A Dec. 8 report from that agency said the lab didn’t have enough personnel to “accurately” perform PCR tests and didn’t have the freezers needed to store samples, which led to more than 41,000 not being processed.

The lab also didn’t do quality control tests on a machine used to analyze samples, its workers failed to follow guidelines for performing rapid tests, it didn’t properly report test results to government authorities and didn’t maintain confidentiality of patient information at various points, according to the review.

Representatives from the Illinois Attorney General’s Office and Illinois Department of Public Health have also they’re investigating complaints against the Center for COVID Control.

The Minnesota Attorney General’s Office sued the company and its lab, alleging they provided customers with incorrect or falsified results, never sent some customers their results or sent others results later than they had been promised.

Multiple attorney general’s offices in other states told Block Club they have received complaints about Center for COVID Control sites.

Credit: Provided

Credit: ProvidedThe Better Business Bureau, a non-government agency, is also looking into complaints about the business, said Steve Bernas, president of the agency’s Chicago division. The organization has given the Center for COVID Control an “F” rating, its lowest.

Experts have also raised questions about the company’s billing practices.

Doctors Clinical Lab, the lab Center for COVID Control uses to process tests, makes money by billing patients’ insurance companies or seeking reimbursement from the federal government for testing. Insurance statements reviewed by Block Club show the lab has, in multiple instances, billed insurance companies $325 for a PCR test, $50 for a rapid test, $50 for collecting a person’s sample and $80 for a “supplemental fee.”

In turn, the testing sites are paid for providing samples to the lab to be processed, said a person formerly associated with the Center for COVID Control.

In a January video talking to testing site operators, Syed said the Center for COVID Control will no longer provide them with PCR tests, but it will continue supplying them with rapid tests at a cost of $5 per test. The companies will keep making money for the rapid tests they collect, he said.

“You guys will continue making the $28.50 you’re making for the rapid test,” Syed said in the video.

Any time there is money flowing between a provider to any kind of patient, it raises concerns about the United States’ anti-kickback statute, said Jeb White, CEO of Taxpayers Against Fraud, a nonprofit dedicated to fighting fraud.

The statute prohibits organizations from receiving money in exchange for things like referring patients or patronage to a lab.

“At the very least, it is worth a heightened level of scrutiny to see if there is any quid pro quo playing out here,” White said.

Employee Allegations

Former employees of the chain told Block Club they had concerns as soon as they started working there — and the company’s issues worsened as the owners expanded when the lab already couldn’t keep up with tests. Tests were kept in unrefrigerated bags, workers were told to lie to people calling in for results and tests were billed to the government even when people had insurance, among other issues, former employees said.

The company has denied their allegations.

Former employee Christine Morales and another former employee said their worries grew as the company expanded and started receiving more tests than it would process on a given day.

When unprocessed tests came in from the company’s sites, many were kept in black or white trash bags, not refrigerated, that would pile up around the office, Morales and the other former employee said. Eventually, the company got biohazard bags and kept tests in those — but many were still left unrefrigerated for days at a time, the two said.

Toward the end of Morales’ time at the company in early December, “they were starting to stack up pretty bad. … You couldn’t even walk. Bags everywhere,” Morales said. “They were at least five or six days behind on their tests, processing the tests.”

Credit: Provided

Credit: ProvidedMorales and the other former employee said they worried the tests were kept unrefrigerated for so long that their samples died and, when tested, provided false negatives for many people.

At one point, when Illinois Department of Public Health inspectors came to visit, workers put bags of tests in a U-Haul parked behind the building and put other bags in a backroom because they didn’t want the inspectors to see the tests, two former employees said.

Around Dec. 10, the former employee was going through unrefrigerated samples when she saw some had been collected Nov. 28 and 29, she wrote in an affidavit for the Minnesota Attorney General’s Office. She had been told samples left out unrefrigerated for so long were “dead” and could not deliver accurate test results, so she asked a manager what to do, she wrote.

The manager “told me that I should enter the data and send the dead samples to the lab for testing anyways,” the former employee wrote. “She said that I should change the collection date on the samples to a more recent date so that it appeared like the samples could still deliver an accurate result.”

Morales and the other former employee said they were also concerned about how they were told to work with customers. They sometimes had to work for the company’s call center “when they got really backed up,” Morales said. Patients would call in, saying they hadn’t received their test results in the time promised by the Center for COVID Control.

That was often because the test hadn’t yet been processed, Morales and the other former employee said. But workers were told to tell customers they hadn’t gotten results because their test was “inconclusive,” the two said.

“We were to tell them that their results were inconclusive and to go and retest — even though their test had not even been touched by the lab staff yet,” Morales said.

Credit: Provided

Credit: ProvidedMany customers also called questioning why they got a negative result from Doctors Clinical Lab but had tested positive through another lab, Morales said.

The other former employee said those calls were distressing, as callers would say they had symptoms of COVID-19 and had been exposed — but hadn’t gotten their results. The former employee said they had to tell people their result was negative or, if it hadn’t been processed yet, say it was inconclusive.

“And I’m thinking, ‘Oh my God, these people are positive. They’re just not getting their test run at the right time. Their test is a dead sample, most likely, because it was sitting out for hours and days. This is ridiculous,’” the former employee said. “I felt so bad.”

“save and print,” Morales and the other former employee said.

Workers would normally review a customer’s information, including their insurance information, and manually input information that was missing or incorrect, Morales said. But when they were backed up, workers would just bring up a person’s information, save it and print it, without ensuring their insurance information was accurate and without trying to contact people to get missing insurance information.

That meant many people’s “bill” for testing didn’t go to their insurance company, even if they had private insurance — it went to the government, Morales and the other former employee said.

“Save and print” happened frequently from August until Morales left in December, she said. Anywhere from 5,000 to 7,000 people on a busy night might get “save and printed,” she said.

There were also times when the company’s software didn’t work properly, so workers couldn’t access a person’s information to ensure their test would be billed correctly, and times when workers had to manually input patients’ information, a former employee said. In those instances, they’d only collect someone’s name, date of birth and email, so the person’s test was billed to the government even if they had insurance, the former employee said.

Often, if there was an issue with someone’s insurance information — like if their company didn’t appear in the dropdown menu workers used to determine where a test would be billed — workers would select the COVID Relief Fund instead of the person’s insurance, the former employee said.

“I would estimate that I selected the HRSA COVID-19 relief fund for over 90 [percent] of the COVID-19 PCR tests I entered into the [Center for COVID Control] database, because the consumers (from across the country) did not enter any insurance information, entered partial insurance information, or entered insurance information about a provider that was not available for me to select from the drop-down menu of” the database, the former employee wrote in their affidavit.

Credit: Colin Boyle/Block Club Chicago

Credit: Colin Boyle/Block Club ChicagoCustomer Complaints

People going to Center for COVID Control sites across the United States have raised questions about numerous issues: dirty sites, long lines, crowded rooms, workers not wearing masks or gloves, workers trying to charge for tests that should be free or telling people to put down that they don’t have insurance when they do, among other problems.

But chief among many people’s concerns has been getting their results and ensuring they are accurate.

Center for COVID Control sites test thousands of people per day, and many have gotten results as expected. But Block Club spoke to people tested at various sites who said they never received results, experienced long wait times — sometimes weeks — before getting results or got back results that didn’t make sense to them.

Robert McNees, of Rogers Park, stopped by a Center For COVID Control site with his family Dec. 22. But the facility was crowded and “chaotic,” and the family wasn’t given instructions for doing the tests, McNees previously said. They opted not to take the tests or turn them in — but about five hours later, every member of the family was emailed a negative result from the company, he said.

Kristen Wylie, of Kalamazoo, Michigan, said she and her partner tested five times over a two-week period at one of the chain’s sites in her area. Her partner tested positive through a rapid test at the site on Dec. 20, but they both got negatives when they tested at the site in the days after that. They then got a PCR test at an unrelated pharmacy and both came back positive.

Trevin Cox, of Logan Square, stopped by a Center for COVID Control testing site Dec. 23 after being exposed. The site’s rapid test gave him a negative result, as did a rapid and PCR result at a pop-up under another chain. But Cox lost his sense of smell, had a fever and had other symptoms. An at-home test came back positive.

Jacob Bennett, of Lakeview, was tested Dec. 21 and still hasn’t received his rapid test results.

“It’s not useful if they don’t give you the results that were promised,” Bennett said. “I don’t have any reason to think that the actual testing is problematic — but not getting a result defeats the entire purpose.”

A Denver woman, who asked that her name not be used, took rapid and PCR tests Oct. 18 at a Center for COVID Control site in Colorado; her rapid result was positive. But her company required a PCR result, which the site hadn’t sent her. She called in, waiting about an hour and a half to speak to someone with the Center for COVID Control — and the worker she eventually reached told her, essentially, “We don’t know,” she said.

About a week after taking the test, the woman got her result emailed to her — and the PCR results said she was negative, she said. A PCR test she took at a state-run facility showed she was positive.

“Out of the three [tests] I took that week, theirs was the only one I was told ‘negative’ — and the one I waited the longest for,” she said. At another point, she said, “Which is scary because if you get that negative test and you haven’t received others, you’re probably going back out into the population like everything is OK.

“While that negative didn’t mean a whole lot to me, I was angry for the sake of others who may have been getting it and therefore spreading it. … You’re a huge role in people knowing that they’re positive and not spreading it. So if you’re giving out wrong results or fake results … that’s a huge issue.”

Credit: Colin Boyle/Block Club Chicago

Credit: Colin Boyle/Block Club Chicago‘Covid Money’

No one at the Center for COVID Control talked about slowing down, despite the frequent backlog in tests, Morales said.

A few more office workers were hired to go through the specimens, but the team did not expand substantially even as it was inundated with tests and it began taking five days and longer to get people results, former employees said.

“I don’t honestly know” why the company expanded when it was struggling to keep up with tests, Morales said. “But they were growing very, very fast and didn’t accommodate when it came to the staff and being able to put more staffing in there for whatever reason.”

A third former employee said there was not enough workers in the call center, and there were “issues” with taking calls from customers. More call center workers were added later, that former employee said.

Company leaders would talk in the office about the money they were getting from PCR and rapid tests, at one point saying they were bringing in more than $1 million per day, Morales and the second former employee said.

“I heard [Syed] talking to one of the … managers about how he made $4 million that week, and I heard them discussing which new cars they were planning to buy,” the former employee wrote in her affidavit. “I felt disgusted to hear [Syed and the Center for COVID Control] were making so much money from COVID-19 testing, when the samples were so often not processed or not processed accurately.”

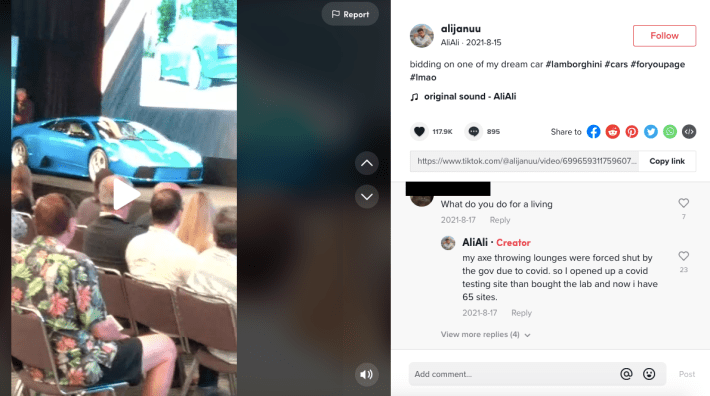

And Syed has posted repeatedly on social media about using “covid money” to buy luxury cars. Siyaj bought a $1.36 million home in November, USAToday first reported. Syed has posted about buying cars worth hundreds of thousands of dollars, including a Ferrari that cost $3.7 million.

In a post where Syed is shown bidding $400,000 for a Lamborghini at a car auction, someone asked him what he does for a living.

“My axe throwing lounges were forced shut by the gov due to covid,” Syed wrote on Aug. 17. “So I opened up a covid testing site than bought the lab and now i have 65 sites.”

In an Aug. 29 video where Syed talks about buying a Lamborghini Countach luxury sports car, someone asked, “Oil money?” Syed replied, “Not even sure what means.. but no covid money.”

In another post, someone asked Syed how could he afford “all those cars.” “Covid testing,” Syed replied. “Rapid and pcr both.”

And in an exchange Dec. 20-21, someone criticized Syed’s business because they’d “been waiting for 2 weeks” for PCR results, he wrote.

“Give us another shot,” Syed wrote. “We are ready for the surge now.”

Though many of the Center for COVID Control’s sites and its website still prominently advertise PCR tests, and Chicagoans have gone to the sites looking to get PCR tests, Syed has told testing site owners the company is no longer offering such tests because its lab can’t handle it.

“About three weeks ago, we decided we were gonna stop PCR testing because of just the overwhelming amount of tests that were coming in,” Syed said in a video he posted Jan. 6 to the YouTube page for his wedding video business. The video was removed after reporters asked about it.

At that point, the chain was doing about 10,000 tests per day, and the majority of the company’s money was coming from PCR tests, Syed said in the video. As of Jan. 6, when he posted the video, the company was doing 90,000 tests per day, he said.

It’d be an “absolute nightmare” to bring back PCR tests under those conditions, so the Center for COVID Control won’t bring them back, Syed said in the video.

“No lab in the country can come anywhere near doing 100,000 tests a day, which is what we would need them to do,” he said. “Therefore, we cannot go back to having PCR back.”

READ MORE

• Center For COVID Control Got $124 Million From Feds While Telling Workers To Lie About Results, Throw Tests In The Trash, Ex-Employees Say

• Center For COVID Control Faked Test Results, Minnesota Attorney General Says In New Lawsuit

• COVID Tests Seemed To Vanish Just When Chicagoans Needed Them Most — And Despite Officials Predicting Surges For Months

• COVID-19 Testing Chain Opened Pop-Ups Across The US. Now, It’s Temporarily Closing Amid Federal Investigation And Mounting Complaints

• Be Cautious Around COVID-19 Testing Pop-Ups, Illinois Attorney General Warns

• COVID Test Shortage Forces Chicagoans To ‘Hell-Hole’ Pop-Up Sites With Unmasked Workers, Missing Results

Block Club Chicago’s coronavirus coverage is free for all readers.

, an independent, 501(c)(3), journalist-run newsroom. Every dime we make funds reporting from Chicago’s neighborhoods.

Click here to support Block Club with a tax-deductible donation.

Thanks for subscribing to Block Club Chicago, an independent, 501(c)(3), journalist-run newsroom. Every dime we make funds reporting from Chicago’s neighborhoods. Click here to support Block Club with a tax-deductible donation.

Listen to “It’s All Good: A Block Club Chicago Podcast” here:

This content was originally published here.