Across Colorado, the county agencies charged with investigating child abuse still need hundreds more caseworkers to keep up with caseloads, according to consultants hired by the state in 2016 after widespread failures in protecting abused children.

The caseworker deficiencies are laid out in a new report from the Colorado Department of Human Services, the state agency that oversees all child protective services in the state, and follow years of struggles to hit benchmarks developed after reports of child deaths, unabated abuse, and a general lack of resources for the volume of child welfare cases prompted a workload audit in 2014.

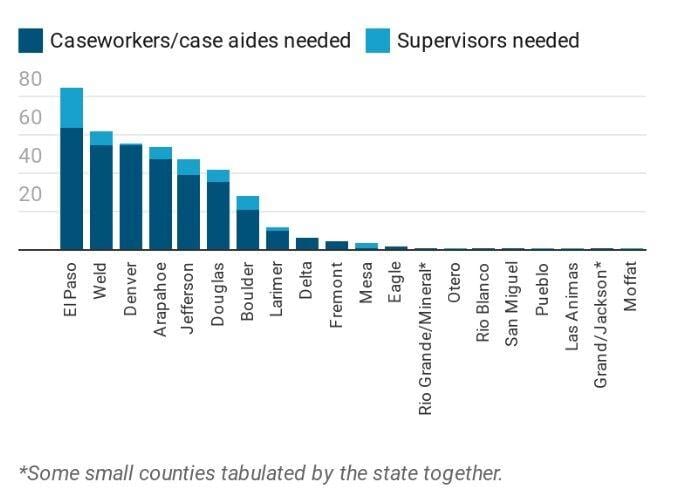

In all, counties throughout the state need 346 additional caseworkers and 65 additional supervisors to manage the recommended number of caseworkers.

But the needs aren’t uniform. Some counties need dozens of additional staff to hit the state’s caseload-per-caseworker goals, while other counties exceed the benchmarks.

El Paso County is among the worst in the state when it comes to caseworker need, the state report shows. The county would need to hire 64 caseworkers, or about one-fifth of the total need in the state, and about 20 supervisors, or a little less than one-third of the total need statewide, to keep up with the county’s caseload.

Among the state’s most populous counties, only Weld and Douglas counties surpass El Paso County’s need for more caseworkers.

Denver also has significant shortages, with a staff deficiency of 55 caseworkers.

Despite the shortages, the state Legislature and Gov. Jared Polis’ administration during the last legislative session provided no additional funding for counties to increase child protective staffing, bringing an end to five years of funding increases aimed at closing a staffing gap identified by a Colorado State Auditor workload study in 2014. The auditor’s report, conducted by a consulting firm, found that Colorado’s overburdened child-protection system at the time needed 574 additional caseworkers — a 49% increase — and 122 new supervisors.

In the five years after the workload audit, the Legislature provided funds that allowed counties to hire 418 additional child-protective workers.

The 2020 reversal in the state’s commitment is due to a strained state budget in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, according to Joe Homlar, director of the state’s child welfare division, and other officials.

The Colorado Department of Human Services does not plan to request additional child protective staffing funds in the upcoming legislative session.

“We know that budget reductions are always difficult,” Homlar said. “We also know and hope that they can be temporary. It is our plan and our goal to make sure that we meet this goal and staff up. I can’t tell you what type of situation we’ll be in three months or six months or a year from now, but I can tell you that that is our plan and our goal.”

Former State Rep. Jonathan Singer, a Democrat from Longmont who did not run for re-election due to term limits, said the lack of funding reneges on a commitment that U.S. Sen.-elect John Hickenlooper made when he was governor in 2014. At the time, and following scathing news reports of staff shortages and horrific deaths of abused children who had been referred to the child-protection system, Hickenlooper pledged he would strive to add about 100 child-protective workers annually until staffing gaps were corrected, Singer said.

“A budget is a moral document, and we’ll have to see if we lead with our ethics and values, even in tough economic times,” said Singer, a former child-protective worker in Weld County.

Singer, who was appointed to a legislative seat in 2012, said he had sought to become a lawmaker largely because of the need for reforms and additional staffing he saw .

“I saw firsthand how hard people were working,” Singer said. “It was this colossal quagmire that I was constantly in as a caseworker. There was never enough time to do the work to protect kids.”

Child-protective staff in counties across the state are in charge of assessing child-abuse referrals and determining whether children need to be removed from families to save them from serious injury or death. They also make crucial decisions, such as whether foster care or adoption are appropriate or whether children in peril can stay with their families with appropriate support services.

Officials with the Colorado Department of Human Services wrote in a 2018 budget request submitted to state lawmakers that correcting staffing shortages was needed to bring Colorado in line with child-protective staffing in other states.

Colorado child-protective workers “manage more cases than compared to the national average,” the budget document described, further noting that a state survey found that about two-thirds of child-protective workers in the state described their volume of assigned work as “heavy and unmanageable.”

And the 2018 budget request further stated that the extra staffing would help bring Colorado into compliance with federal standards meant to ensure children receiving child-protective services are obtaining necessary care, educational stability and adequate physical and mental health resources.

Fewer than 30% of children in foster care were graduating from high school, compared to nearly 80% among the general population, the budget request added. Additional child-protective caseworkers would help improve those graduation rates, the budget request predicted.

In June, officials with the state Human Services Department submitted to federal regulators a report that stated graduation rates for foster children remained low. That report also stated Colorado “was not in substantial conformity” with federal standards meant to ensure children receiving child-protective services in the state remain safe in their homes whenever possible and appropriate and have permanency and stability in their living situations.

In addition, the state is not meeting federal standards meant to ensure family relationships are preserved when children must be separated from their families, according to that report.

About 43% of children who must be separated from their parents to protect them from abuse are placed with a relative initially, the report added. Caseworkers must do more to encourage fathers to engage in community services and more work still must be done to ensure children in protective services are having their physical and mental health needs met, the report further stated.

Colorado also needs to improve child-protective staff training, particularly in light of a troubled rollout of an overhauled statewide computer system that tracks abuse cases and referrals, according to the report.

Despite those concerns identified in the report and the lack of funding to correct the child-protective staff shortages across the state, Homlar, Colorado’s child welfare director, said he remains confident that the state’s Human Services Department is on the right track and will ensure children are adequately protected from abuse.

“We’re very confident in the work that we’re doing in partnering with families to make sure that they have what they need to prevent maltreatment and improve well-being,” Homlar said. “We’re very happy with our progress. I’m very confident about our workforce and our services, but there are always opportunities to enhance what we do.”

Julie Krow, the El Paso County Department of Human Services executive director, said the state has helped her agency improve child-protective staffing after the first workload study in 2014 found El Paso understaffed by 324 caseworkers and case aides, but she stressed that more still needs to be done.

Child-protective work is stressful and difficult, though rewarding when it ends up saving a life, she said. Her staff has the additional burden of navigating an overhauled computer system for tracking abuse cases that still isn’t fully operational.

“They all came into this because they care about children,” Krow said. “But the workload is still high. The burden is higher than we wish it would be.”

Additional staffing “just can’t come quickly enough for counties, but more importantly Colorado’s children,” she said.

During 2020, Krow said, the number of calls about child abuse have decreased, but she said that’s likely because fewer children were in school, where teachers have a duty to report signs of child abuse.

“There’s no reason to think that abuse has gone down,” she said. “We expect the volume to start going up. When school is in session, volume goes up and when school is out of session, volume goes down.”

303-257-2601

This content was originally published here.