Colorado’s summers are getting warmer and drier, and it’s all because of climate change.

At its core, climate change is simply a change in the usual weather that a location experiences over time — the 80218 zip code in Denver, the state of Colorado, the contiguous United States or the entire planet. Thanks to modern technologies and weather tracking systems, scientists are able to visualize the changes in our weather and climate on every scale.

There are numerous reasons for that climate change (NASA’s Climate Change page is a great resource), spanning from the Earth’s distance from the sun to humans burning coal, oil and gas, the gases from which “cause the air to heat up.”

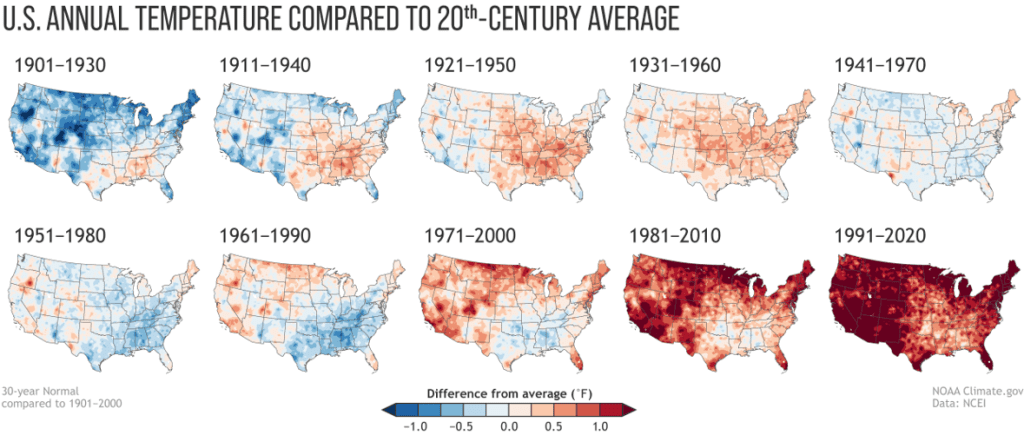

A large chunk of the United States has seen a warming trend in annual temperature (comparing the climate normals from this decade to decades past), most notably in the Western U.S., areas around the Great Lakes, the Northeast and Florida — so, almost everywhere.

Before we dive into the science behind Colorado’s warming summers, here are some global figures about climate change.

Global temperature rise

The planet’s average surface temperature has risen about 2.12 degrees Fahrenheit since the late 19th century, driven largely by increased carbon dioxide emissions and other human activities. Most of the warming occurred in the past 40 years; 2016 and 2020 are tied for the warmest years on record.

Warming oceans

The ocean has absorbed much of this increased heat, with the top 100 meters (about 328 feet) of water showing warming of more than 0.6 degrees Fahrenheit since 1969. The Earth stores 90% of its extra energy in the ocean.

Sea level rise

Global sea level rose about 8 inches in the last century. The rate in the last two decades, however, is nearly double that of the last century — and accelerating slightly every year.

Ocean acidification

Since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, the acidity of surface ocean waters has increased by about 30%, and is the result of humans emitting more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere and hence more being absorbed into the ocean.

Decreased snow cover

Satellite observations reveal the amount of spring snow cover in the Northern Hemisphere has decreased over the past five decades and the snow is melting earlier.

Extreme events

Since 1950, the number of record high temperature events in the United States has been increasing, while the number of record low temperature events has been decreasing. The U.S. also is seeing increasing numbers of intense rainfall events.

In 2020 alone, there were 22 natural disasters that caused at least $1 billion dollars in damage — the most in a year. Between 2001 and 2010, the United States averaged 4.8 billion-dollar natural disasters per year, which increased to 10.9 between 2011 and 2020.

The west’s extreme drought and devastating fire season in 2020 was included on the list of billion-dollar disasters for the year — and its due to warming temperatures and a changing climate that’s likely to continue.

Summer warming

The U.S. meteorological summer season, which runs from June 1-Aug. 31, has warmed by at least 2.0 degrees since 1970, according to Climate Central, an independent organization that surveys and conducts scientific research on climate change.

In Denver and Colorado Springs, the summer season has warmed by 2.6 degrees since 1970 — higher than the national average. Grand Junction’s average summer temperature is up by 1 degree, smaller but still notable.

Higher average temperatures increase the number of extreme heat days. Denver used to average about five days of 95-degree heat prior to the 1970s; now it’s more than 20 days. Colorado Springs used to experience 11 days of 90-degree heat in 1970, now the city feels 30 days of intense heat per season. Grand Junction saw an average of four days of 100-degree heat in 1970 and now that number has increased to nine days.

On average, Grand Junction experiences higher temperatures throughout the year because it’s a dry, arid desert climate, so temperature and precipitation extremes are more difficult to reach.

But as we’ve seen as of late, temperatures have had no trouble reaching dangerous levels several times this year already (don’t forget the record-shattering heat wave we experienced before the peak summer heat even set in).

Summer nights are typically where Colorado cities balance out the daily temperature average due to the fact that they cool off efficiently in normally dry air. But data is showing that even our nighttime temperatures are rising.

In Denver, the average nighttime temperature has risen by 1.8 degrees since 1970; it’s 1.7 degrees warmer in Colorado Springs and 0.3 degrees warmer at night in Grand Junction on average.

NASA says the western U.S. will see more intense “droughts and heat waves” and less intense cold snaps.

“Summer temperatures are projected to continue rising, and a reduction of soil moisture, which exacerbates heat waves, is projected for much of the western and central U.S. in summer. By the end of this century, what have been once-in-20-year extreme heat days are projected to occur every two or three years over most of the nation,” NASA’s climate website said.

Water supply and wildfire concerns will lead the news as our climate continues to change in Colorado.

Of course, we will still have the occasional crippling winter storms and arctic air outbreaks, but warmer and drier summers spell issues for many industries in Colorado and, needless to say, for anyone who calls this state home.

Andy Stein is a freelance meteorologist.

This content was originally published here.