A “southern district” concept was approved by a majority of the commissioners at Wednesday night’s congressional redistricting commission meeting, meaning some big changes could be coming to the preliminary draft congressional map first released in late June.

The “southern district” concept would be built around the idea that Colorado’s rural ethnic minority communities should be drawn into a single congressional district, in order to empower them to vote as a bloc in support of candidates of their choice.

The commissioners voted 7-4 to have their staff draw a map that would keep together Pueblo, Otero, Huerfano, Las Animas, Alamosa, Conejos, Costilla, Mineral, Rio Grande, Saguache, Archuleta, La Plata and Montezuma Counties.

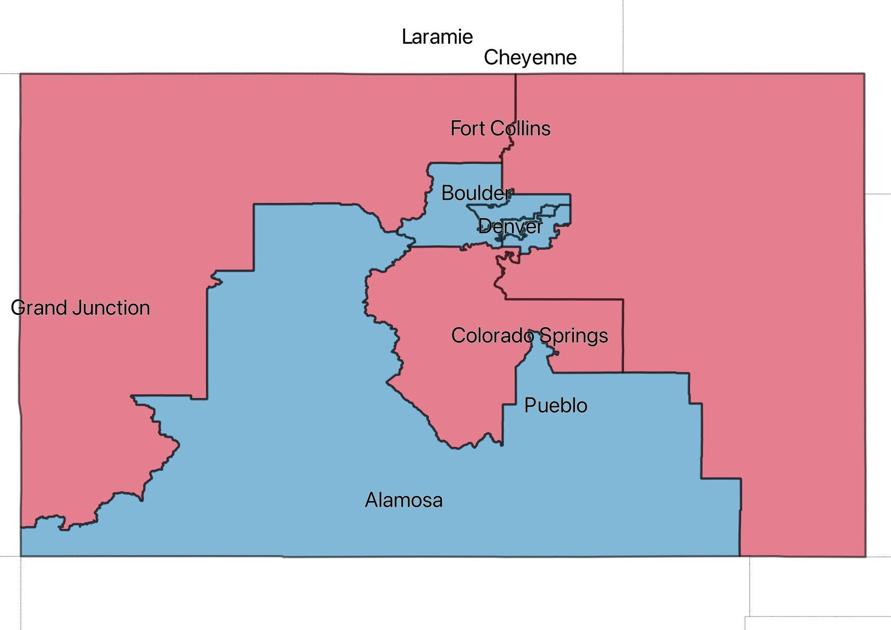

Making the change would mean ditching the district arrangement used for the preliminary draft congressional map, which is instead built around the idea of splitting the state’s rural areas into two expansive eastern and western districts. Such an approach splits some of the state’s rural ethnic minorities.

The redistricting commission’s staff produced the “preliminary draft” map in June.

The decision by the commission comes as several organizations have lodged complaints with how the preliminary draft maps affect minority communities, and just days before the commission’s staff releases a new draft map, which could come as early as Friday.

At a public input hearing Saturday in Colorado Springs, Mark Grueskin, an attorney and lobbyist for a secretly-funded 501c4 nonprofit organization, told the commissioners that failing to empower ethnic minority communities would not only diminish their political voice, but it could also lead to litigation.

To explore how the redistricting criteria can affect a map, Colorado Politics compiled several different maps, each with district population deviations of less than one percentage point and using some of the same data being used by the commission, but drawn prioritizing different concepts. Some seem unlikely, but they illustrate how the redistricting criteria manifest in different maps, while some might end up resembling the map ultimately drawn by the commission.

Grueskin told the commissioners that the language of Colorado’s constitution, which was amended by a set of voter-approved 2018 ballot measures creating the new independent redistricting commission system, so specifically requires the commission to empower minority communities that not doing so could end up with a lawsuit over minority vote dilution.

Some of the commissioners challenged Grueskin’s interpretation, but before voting to explore the idea in future drafts of the congressional map, the commission met in private executive session with their lawyers to discuss the matter.

After emerging from the executive session, the commission voted 7-4, with one absent, directing the commission to come up with draft maps that seek to keep minority communities together, vis-à-vis the “southern district” concept.

Colorado’s congressional redistricting commission debuted the “starting point” congressional district map, with eight districts instead of seven and that will be altered and adjusted over the coming months, before settling on a final version of the map this fall.

Some prominent organizations have already submitted versions of a map that attempts the same thing, and they illustrate what kinds of changes would result, compared to the current preliminary draft map.

LULAC, the League of United Latin American Citizens, submitted a map that would divide Colorado Springs in half, grouping the southern half of the city with Pueblo, the San Luis Valley, portions of southwest Colorado, extending to Four Corners and reaching north into Pitkin and Eagle Counties. The district would have a 23% Hispanic voting age population composition, and would favor Democrats by about 10 percentage points. Its voting age population would also be 5% Black and 2% Native American. The LULAC map notably includes Greeley with the northeastern part of the state, which is another area where minority voting patterns could suggest that doing so dilutes their voting power.

LULAC, the League of United Latin American Citizens, submitted a map that would divide Colorado Springs in half, grouping the southern half of the city with Pueblo, the San Luis Valley, portions of southwest Colorado, extending to Four Corners and reaching north into Pitkin and Eagle Counties.

CLLARO, the Colorado Latino Leadership, Advocacy and Research Organization, also similar submitted a map proposal based around a southern congressional district, but without cutting into Colorado Springs, and adding more of eastern Colorado, including part of the Grand Junction area. In their map, the southern district would be 24% Hispanic, 2% Black and 5% Native American, and it would have a nearly even partisan split.

CLLARO, the Colorado Latino Leadership, Advocacy and Research Organization, also similar submitted a map proposal based around a southern congressional district, but without cutting into Colorado Springs, and adding more of eastern Colorado, including part of the Grand Junction area.

Colorado Common Cause, a prominent left-leaning political advocacy organization, submitted a map that, like the LULAC map, splits Colorado Springs in half. But unlike the LULAC map, their southern district would include Custer, Fremont, Teller and Park, keeping it more compact instead of extending to the eastern edge of the state. Their map would be 25% Hispanic, 6% Black, 5% Native American and 3% Asian voting age population. It would be somewhat competitive, with a slight Republican-lean. The Common Cause map does not include some of the western-most counties included in the motion made to direct the staff’s future mapping.

Colorado Common Cause, a prominent left-leaning political advocacy organization, submitted a map that, like the LULAC map, splits Colorado Springs in half, but unlike the LULAC map, its southern district would include Custer, Fremont, Teller and Park, keeping it more compact instead of extending to the eastern edge of the state.

The Colorado Hispanic Chamber of Commerce submitted a congressional map proposal, but it does not fit the direction that was provided Wednesday night, because it does not keep Pueblo in the same district as the San Luis Valley.

This content was originally published here.