Colorado has a stockpile of more than 350,000 doses of COVID-19 vaccine that must be administered before they expire in two months, a challenging feat as fewer and fewer people are getting inoculated each week.

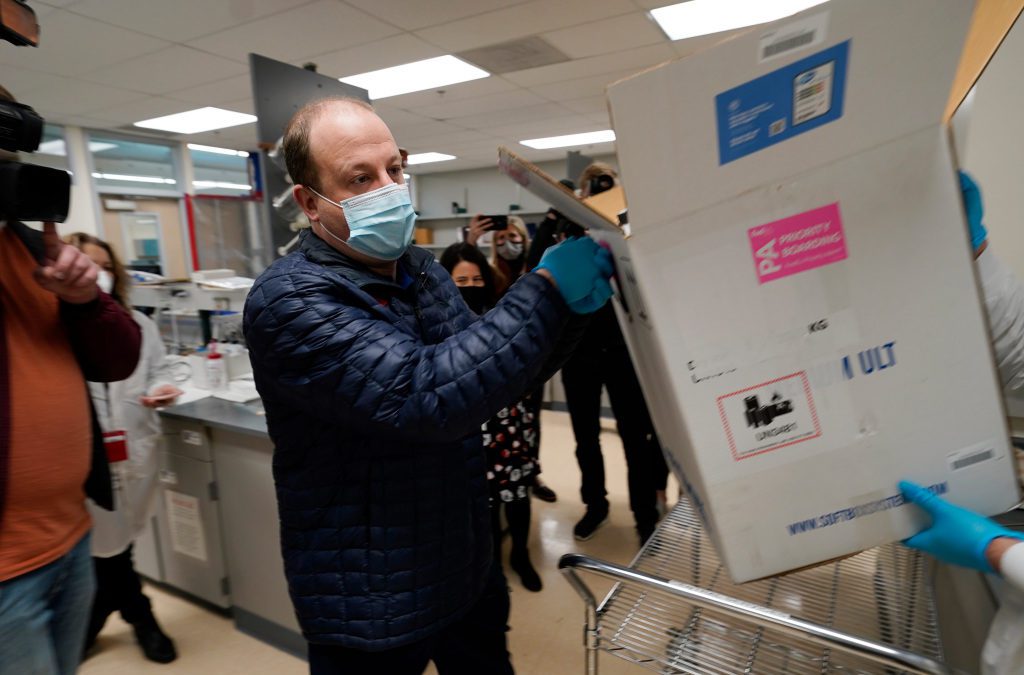

For now, state officials, including Gov. Jared Polis, said they expect those doses — which are scarce globally and in high demand in countries experiencing a surge in infections — will get used before they go to waste. But that will require stemming the decline to largely maintain the current level of vaccine administration.

A majority of the stockpile contains second doses that are needed for people who received their initial shots of vaccines developed by Pfizer and Moderna, according to the governor.

While the state still has time to increase uptake of the vaccines, the clock is ticking — especially if officials want to send the doses back to the federal government to redistribute elsewhere, according to public health experts.

“If the state is going to say they are going to use it all, it really is incumbent on them to find a way to use it all,” said Ruth Faden, founder of the Johns Hopkins Berman Institute of Bioethics, adding, “It’s absolutely ethically awful that COVID-19 vaccines should become useless because they just lie there past their expiration date.”

Public health experts said the ideal solution is to get those 352,533 unused doses into Coloradans’ arms. But the state doesn’t have a lot of time to determine if it needs to redistribute the doses.

“We can give them back to the federal government where they have a program where they donate them overseas,” Polis said during a news conference this week. “First and foremost, we’d like to use them, that hopefully all this will work and they will get into arms.”

Other states, including Arkansas and North Carolina, also have stockpiles of COVID-19 vaccines with looming expiration dates, STAT reported this week.

“The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention notified us that they are exploring ways to return vaccine doses that are held in high volumes at central storage facilities to the federal government for redistribution,” a spokesperson with the state Department of Public Health and Environment said in an email.

Colorado already has donated more than 300,000 doses of COVID-19 vaccines to the federal pool that was allocated but not shipped to the state, according to the state health department.

The agency is working to reach those who have not yet gotten inoculated via phone calls, text messages and mobile vaccine buses. But it faces a significant challenge in its outreach: fewer Coloradans are seeking out the shots even as they have become more widely available.

Colorado’s vaccine distribution peaked with 429,556 doses administered the week of April 4 and has been declining every week since, with the exception of one week in June.

Last week, the state administered just under 50,000 doses, which is fewer than in late December, when the vaccines were not widely available to the public. But it was only a 1.6% drop from the prior week, suggesting it’s possible the decline is slowing.

Colorado administered 50,173 doses the week of July 4, which was down 19% from the 61,870 doses put into people’s arms the week of June 27.

And 6% of the 3.2 million Coloradans — nearly 200,000 people — who’ve received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine have missed getting their second shot within the recommended timeframe.

Of the 4.9 million Coloradans eligible for the vaccines, more than 1.3 million have not yet been inoculated.

“It’s rather distressing that people are not getting vaccinated when they need to and when it is available at the same time that people in other countries are desperate for the vaccine and are clamoring for it and don’t have it available,” said David Magnus, director of the Stanford Center for Biomedical Ethics.

It’s possible that demand for the vaccines could increase once again, including if employers require their workers to get the shots and if they become available to children under 12. The recent concern about the widespread delta variant could also motivate more people to inoculated, said Beth Carlton, an associate professor of environmental and occupational health at the Colorado School of Public Health.

The upcoming academic year could also incentivize more teens and their parents to get inoculated. School districts have said they won’t mandate the shots, but they are highly encouraging them for students returning to in-person learning.

“What we need is as many people as possible to get vaccinated,” Carlton said. “Hopefully, we find that magic wand.”

Denver Post reporter Saja Hindi contributed to this report.

This content was originally published here.