Before dawn Thursday morning, Montana Nash finished another 12-hour shift as a nurse in the intensive care unit at Swedish Medical Center in Englewood and hurried to her next appointment.

It had been a normal shift by the standards of the current surge of coronavirus across Colorado, which is to say it had been awful. Nash works as the charge nurse on her floor, a trauma ICU that has been converted into the COVID ICU, 16 beds becoming 26 to keep up with incoming cases.

In the spring, the staff would hold mini parades for patients who were discharged from the floor, clapping and playing music as another survivor was wheeled out. But this fall, with doctors, nurses and other staff members simply exhausted by the pandemic, there hasn’t been the energy for celebration.

COVID-19 IN COLORADO

The latest from the coronavirus outbreak in Colorado:

- MAP: Cases and deaths in Colorado.

>> FULL COVERAGE

Patients come in. A few days later they are intubated. A week or so later, many are dead. And the pattern repeats. Sadness and fatigue and fear of the next wave cling to the staff throughout their shifts.

Nash’s assigned patient Wednesday night into Thursday morning was a woman who had caught the coronavirus in a rehab facility. Now, she was in multi-system organ failure, a dialysis machine continuously filtering her blood.

“I feel like everyone I’ve taken care of this week is just dying,” Nash said she told the doctor on call.

That’s the way it’s going, the doctor responded.

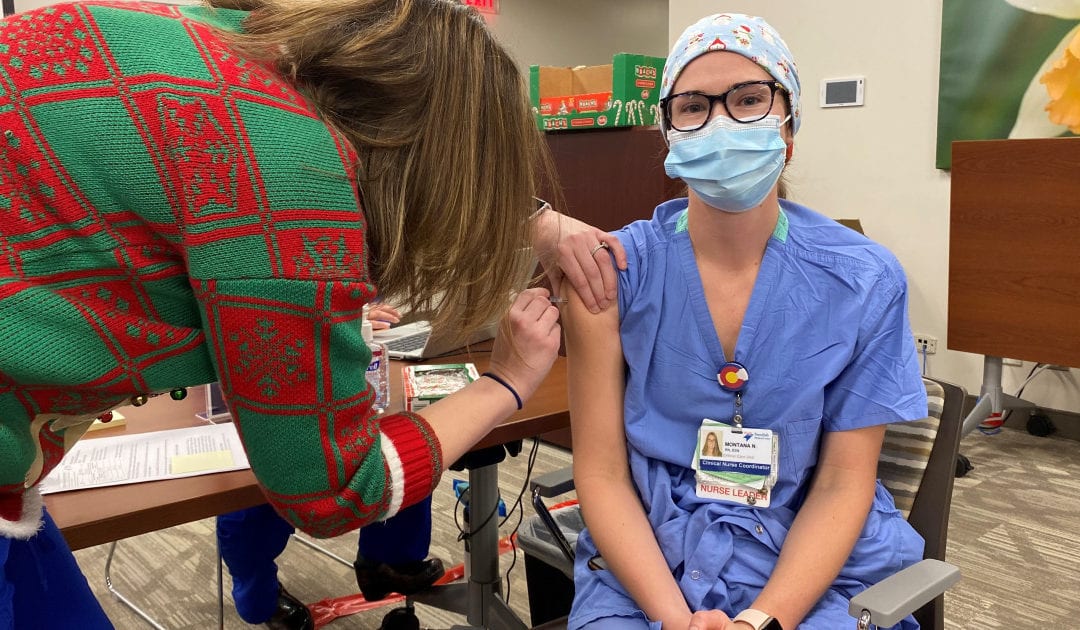

Shortly after 5 a.m., Nash finished briefing the incoming charge nurse and headed downstairs to the hospital’s second floor. There, in an otherwise bland conference room, she found a surprisingly large number of hospital staff and administrators gathered. Many were wearing holiday sweaters. People were smiling.

“It felt like you were going down for some celebration,” Nash said.

She rolled up the right sleeve of her scrubs top. A woman in a red-and-green snowflake sweater prepared the syringe. At 5:17 a.m., needle hit skin, and Montana Nash, having worked all night to end the pandemic, took one more bleary-eyed step to do just that. She got vaccinated against COVID-19.

“It’s really exciting,” she said. “The best way to describe it is there is light at the end of a very dark tunnel.”

Getting shots in arms

After receiving the first shipments of vaccines earlier this week, Colorado hospitals are rapidly getting those doses into the arms of their staff members.

Tens of thousands of health care workers have signed up for appointments to get their shot. A stream of thousands of nurses, doctors, respiratory therapists and other staff are moving daily through makeshift vaccination centers — beginning a steady march toward the hopeful end of the most miserable pandemic the world has seen in more than a century.

“It is rocking,” said Dr. Richard Zane, the chief innovation officer for UCHealth. “It is one of the most important events in the history of science and medicine, and people are excited they are participating.”

The very first doses — what is referred to as Phase 1a in the state’s distribution plan — are intended for health care workers who are exposed to coronavirus patients, as well as staff and residents at long-term care facilities and nursing homes.

But things are moving so fast in some hospitals that they are already looking ahead toward the next phase of the rollout plan — Phase 1b, when health care workers not in contact with coronavirus patients become eligible.

And the state has signaled no desire to draw sharp lines between those two phases or even to stop hospitals from commingling the phases. While the state’s plan on paper is a precisely defined and orderly sequential rollout, the on-the-ground imperative is to make sure the vaccine gets used as quickly as possible with none going to waste.

“Our guidance to the local level is to have five in line when you puncture that vial,” said Colorado National Guard Brigadier General Scott Sherman, the director of the state’s Joint Vaccine Task Force. The “five in line” refers to the number of doses contained within one vial of the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine, the first one approved and the one being administered now. The doses must be used within six hours after the vial is punctured.

“If you only have two in line from 1a but you have three more from 1b, that’s fine. That’s your discretion. We’ve just got to get shots in arms when that vial is punctured.”

From blessings to “Stone Cold Steve Frostin’”

Zane said UCHealth is running 10 vaccination clinics across the state for 12 hours a day, with appointments spaced 15 minutes apart. Invitations to sign up for a time at the clinics have already been sent to 17,191 workers within the UCHealth system, including everyone who is eligible to be vaccinated in Phase 1a.

Zane said UCHealth expects it will soon be able to transition into vaccinating its Phase 1b staff, with everyone at the hospital system eligible for vaccination in the full Phase 1 hopefully having gotten a first dose by the end of January. (The vaccines currently or expected to be used in Phase 1 require two doses spaced three or four weeks apart. Hospitals will also coordinate the second doses for their workers.)

At HealthONE, which includes Swedish Medical Center, Lindy Garvin, the vice president of quality and patient safety, said about a third of the hospital system’s 10,000-member workforce is eligible for vaccination in Phase 1a. She said HealthONE is expecting that the doses it will receive in the first couple weeks of distribution will cover everyone in Phase 1a with an initial shot, with enough left over to move into giving first doses for Phase 1b, though that’s still a little tentative.

“It’s very real-time that things are happening because it’s such a big effort to distribute the vaccine,” Garvin said.

On Wednesday, when HealthONE hospitals began administering vaccinations in Colorado, about 500 workers were inoculated, said Stephanie Sullivan, HealthONE’s assistant vice president for media relations. She said that number was likely to rise to around 1,000 on Thursday.

When Denver Health sent out a survey to its staff to coordinate vaccination scheduling, the hospital received more than 7,000 responses, said Dr. Judith Shlay, the associate director of Denver Public Health. The hospital is expected to receive more than 8,500 doses of vaccine from the first two shipments to the state.

And it’s not just that these long-awaited shipments are finally reaching hospitals and being administered. It’s that the shipments are bringing a positively giddy sense of enthusiasm with them.

People who work at hospitals have described crying at the sight of vaccinations being given. They talk in effusive terms, revealing the stress hospital staff have been under the past 10 months.

“It is beyond exciting,” said UCHealth’s Zane, who also practices emergency medicine at the University of Colorado Hospital. “It is the single most incredible event that I have experienced in my career.”

Today I received the COVID-19 vaccine. Celebrating this once in a generation scientific achievement that will save many lives and define leadership in crisis. #COVID19 #CovidVaccine #sciencematters #onward https://t.co/3MM7DGe2ei pic.twitter.com/72LJmZtL4L

— Richard Zane MD (@richardzane) December 17, 2020

Some tributes have gone a little loopy. The staff at the Yampa Valley Medical Center in Steamboat Springs has bestowed a butt-kicking nickname upon their ultra-cold freezer, which stores the Pfizer vaccine: Stone Cold Steve Frostin’.

At Denver Health, some staff have reportedly begun referring to their ultra-cold freezer as Turbo.

“I love our ultra-cold freezer,” Shlay said. “I have a picture of me in front of it. It is so beautiful.”

Others have viewed the vaccine in more spiritual terms.

At Presbyterian/St. Luke’s Medical Center in Denver on Wednesday, the hospital’s chaplain, Michael Guthrie, showed up to bless the vials of vaccine as the first health care workers there received it. The buzz of inoculation activity in the conference room stopped, and everyone gathered around Guthrie with their heads bowed to take a minute to soak in the moment.

“May this vaccine serve as a light of hope, strength, courage and perseverance,” Guthrie said.

“Amen.”

The long road ahead

Despite this enthusiasm, state officials and hospital representatives caution that the road ahead remains a long one.

Colorado has so far received 46,800 doses of the Pfizer vaccine. Another 95,600 doses of the vaccine from Moderna are expected to be shipped early next week, assuming the federal government gives emergency approval to that vaccine in the coming days. And Sherman said the state is planning on Friday to order another 56,000 doses of the Pfizer vaccine, part of what state officials hope will become a weekly cadence of Friday orders and early-week deliveries.

Despite that haul — close to 200,000 doses, with an equivalent number expected to arrive later to cover second doses for all those in Phase 1 — Sherman said it’s not enough for the state to start looking to move to Phase 2, when vulnerable members of the general public become eligible for vaccination.

An early version of the state’s vaccination plan estimated that Phase 1 would contain more than 330,000 people, though Sherman said the state is still tallying up the counts for the phases in its current plan. Estimates for when the state might reach Phase 2 range from February to late March.

“We really can’t give an estimate until we get a firm grasp on what distribution is going to be,” Sherman said. “We just don’t have that data yet.”

Debate over timing

The uncertainty on timing has led to some tension among those eligible for vaccination in Phase 1.

West Metro Fire Protection District’s board sent a scathing letter to Gov. Jared Polis asking him to rethink the tier system and place fire and EMS personnel in the first level of those receiving the vaccine, pointing out that first responders are often the first ones to encounter COVID-19 patients when they get really sick. Garry Briese, executive director of the Colorado State Fire Chiefs, sent the governor’s office a similar plea.

“We need to be at the same level of other health care providers that are in that tier 1a,” West Metro Chief Don Lombardi said. “Granted those folks are working really, really hard. They’re under some pretty brutal conditions with what they’re facing. But our folks are facing a lot of the same conditions and in some instances doing a lot of the same procedures — when you look at intubation or respiratory-type procedures — in a less-controlled environment than a hospital.”

Lombardi said firefighters are oftentimes responding to nursing homes and assisted-living centers where there is a high risk of catching COVID-19, not to mention disastrous consequences if they were to introduce it into one of those facilities.

“We’re the tip of the spear,” he said. “Those in EMS, those in the 911 system, we are first.”

There’s also the matter of access. EMS personnel, for instance, are in Phase 1b. Those who work for hospitals could receive vaccinations as part of the hospitals’ initial wave of doses. But those who work for independent companies might have to wait for doses specifically designated for Phase 1b.

Still, Scott Sholes, president of the Emergency Medical Services Association of Colorado, said he’s OK with where first responders have been placed on the scale.

“It’s my understanding that the difference between 1a and 1b is not really meant to be something that defines who is more important and who is more at risk,” said Sholes, who also serves as emergency medical service chief at the Durango Fire Protection District. “I don’t see the difference between 1a and 1b that substantially gets my hackles now that I understand they are very close from a time standpoint.”

He added: “I’m more concerned about getting a plan together that makes sure that first responders will work with public health officials to get scheduled.”

Other first responders are also OK with waiting a few weeks. Steamboat Springs Police Chief Cory Christensen, who leads the Colorado Association of Chiefs of Police, said he’s fine with where first responders are on the priority list

“I think we’re fine at 1b,” he said. “We’re in there with other outside line-level first responders — EMS, firefighters, law enforcement. I think we fall on a good scale. We’ve been training around this. We have proper PPE out there. We have good policies in place. And, honestly, we value the hard work and dedication of our frontline health care workers. I’m glad to see they are in the front of the line.”

When the state does expand to broader groups like first responders or, later, the medically vulnerable, state officials don’t intend to be too strict in policing who is getting vaccinated.

“We’re trying not to make this too bureaucratic because it’s really important that we’re able to get vaccines in arms as quickly as possible and not waste any vaccine,” said Jill Hunsaker Ryan, the executive director of the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. “And so we’re leaving it up to the providers’ discretion for them to ask the questions and assess that. But at the state, we’re not requiring any sort of documentation that someone is in a certain phase.”

A sore arm and no fear

Even in the months leading up to the vaccine’s arrival, Nash said hospital staff were abuzz about it. At first, the conversations were skeptical. It’s being developed so fast, people would say.

But as the federal government released data on the safety and efficacy of the Pfizer vaccine, Nash said staff began doing their own research. Some of Swedish’s doctors made videos explaining how the vaccine works and how it was tested. People gradually began to look eagerly toward the day when it would arrive.

When her turn came, Nash said she was not scared or worried about the vaccine’s safety. After getting the shot, she sat in a waiting area for 15 minutes where she was monitored for any side effects. Then she went home and went to bed.

When she woke up early Thursday afternoon, all she felt was a sore arm, similar to a flu shot. Her dad, who lives in Edwards, had posted proudly on Instagram about his daughter receiving the vaccine. And Nash said she feels privileged to be part of a worldwide effort working together to solve the pandemic.

“It feels like in a way,” she said, “you’re part of history.”

Our articles are free to read, but not free to report

Support local journalism around the state.

Become a member of The Colorado Sun today!

$5/month

$20/month

$100/month

One-time Contribution

The latest from The Sun

This content was originally published here.