Before she went to jail and before she overdosed, Brittany Medlin dabbled in getting clean.

She’d make it three days, maybe five. She and her sister, also then struggling with addiction, had been subjects of an “Intervention”-style TV show. The broadcast had sent them both to rehab. Jill Conner, their mom, told Medlin that if she left before the 90 days were up, she couldn’t come home. She left after 93 days. Within two hours of Conner and Medlin’s stepdad, Doug, picking her up from the airport, Medlin was using again.

Medlin tried Suboxone, Conner says, a medication used to pull addicts off of its opioid cousins and keep them from the agony of withdrawal. But she wasn’t ready for recovery, not really. Being high meant feeling normal.

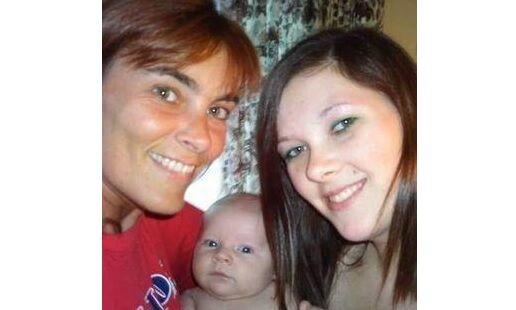

A cheerleader at Rocky Mountain High in Fort Collins, Medlin was a homebody and a momma’s girl. She was a practical joker. — Vaseline on the toilet seat, a rubber band on the sink nozzle. In high school, her first jobs were dressing up like Wendy, of fast-food fame, and a giant Sonic cup. She loved those jobs. She loved music, too. When she was in rehab, she made a list of 200 songs she liked. Conner still has it.

Then she moved to Iowa, setting her on the path to become a sobering example of when people struggling with addiction don’t get help. She met a guy, and through him, she found methamphetamine and OxyContin. She gave birth to Kayden in May 2010, and after a run in with the police, Kayden went to live with her parents. She moved back to Colorado, where she was arrested for stealing, a source of income to feed her habit. She’d moved to heroin, and by 2016, “it got really bad,” her mom says.

In November 2016, Medlin asked a Larimer County judge to lock her up. She was ready, at last, to kick heroin, but she was struggling to do it out in the world. The judge gave her 20 days. She went through withdrawal in jail, an agonizing several days characterized by vomit, diarrhea and intense pain.

On Dec. 13, 2016, she got out. Her mom’s birthday had been two days before, and Medlin would turn 27 on Dec. 17. She stayed up late that first night with 6-year-old Kayden, watching movies. The next morning, she exchanged I-love-yous with her mom before Conner went to work, and Conner texted her later to remind her that Kayden’s Christmas concert was the next night. When Conner came home that night, she found Medlin lifeless in the bathroom. She had been out of jail for 28 hours.

In 2007, researchers published a landmark study in the New England Journal of Medicine that examined death rates among inmates recently released from prison in Washington State. They found that, in the two weeks after release, inmates were 129 times more likely to fatally overdose than the rest of the population. They were nearly 13 times more likely to die, from any cause. Another study in North Carolina put the overdose risk at 40 times higher for recently released inmates.

It is not hard to parse out why. Among other contributing factors, inmates with substance use disorders go through forced abstinence: With no access to drugs in prison or jail, they go through withdrawal and lose their tolerance. When they are released, often without vital behavioral treatment or transitional help, many go back and use the same drug, at the same dosage as before. They may have lost their jobs or homes. But they’ve also lost their tolerance, and what was once their standard dose becomes their last one.

The solution, experts say, is medication-assisted treatment (MAT), a combination of prescriptions like Suboxone or methadone and therapy. The meds help curb the cravings and ward off withdrawal, itself a powerful push toward relapse, and the therapy helps with the underlying addiction and any traumas that may have triggered it. Robust programs in jails include housing and employment services for those recently released, both to help them reintegrate successfully into society and to avoid further triggers or traumas.

At the time of Medlin’s death, MAT did not exist in Colorado jails. Four-and-a-half-years later, more than half offer it, according to a list provided by the state. The Department of Corrections now allows inmates to continue receiving medication if they’ve already started when they enter prison, and the agency offers naltrexone, which helps stop cravings, to inmates upon release, a spokeswoman said.

Statistics about overdoses, in their compressed depersonalization, are ultimately flattened stories of people. Brittany Medlin was a person. She went to jail, voluntarily, to kick her habit. In that way, it wasn’t necessarily forced abstinence. But it was unmoored from a structured recovery, Conner says, and she became a statistic 28 hours later, a beloved daughter and a cautionary tale.

“Having lost my child, I believe MAT medication gives those who struggle with (opioid use) the chance to live to fight one more day,” Conner says. “In jail. Out of jail. We don’t know when they’ll be ready, but we can’t help them at all if they no longer walk among us.”

Many are like Brittany. An estimated 20% of inmates in America’s prison have an opioid-use disorder. Jails and prisons are, in many ways, a frontline in the war against opioid addiction, and all too often, experts say, that battle is fought without the weapon that’s most likely to save lives.

For this story, The Gazette spoke with more than a dozen addiction experts, law enforcement personnel and health care providers who advocate for or are directly involved in medication-assisted therapy. Advocates roundly praised it and said it was a matter of life and death for many involved.

After examining “hundreds” of studies over the years, Rob Valuck, the head of the Colorado Consortium for Prescription Drug Abuse Prevention, said he’s found that addicts have a sub-10% chance of successfully kicking an addiction without MAT. With that type of program included, for inmates or the general population, it rises to a bit below 50%. With a robust program, including housing and employment aid, it bumps to over half. That’s still far below 100%, and in that gap are deaths. But it’s better than the estimated 90% relapse rate of abstinence and therapy alone, as found in a 2007 study published in JAMA Psychiatry.

“We’re just trying to get to coin-flip range,” Valuck said.

Medications like Suboxone and buprenorphine block other opioids from binding to receptors in the brain, blunting abuse of those drugs while stopping cravings and withdrawal symptoms. Many people in recovery are on them long term. They’re administered and controlled by licensed health care providers.

The effort to seed MAT in Colorado jails has been undertaken by people like Valuck, Jill Conner, who became a proponent after her daughter’s death and in her own work in addiction therapy, and J.K. Costello, a doctor and consultant who’s advocated for the program statewide. They were armed with a Rhode Island study that found a 60% drop in overdose deaths after MAT was implemented in prison. Though the numbers in that study were small, researchers called it “remarkable” that such a decrease was possible.

How to handle addicts in jails became a high-profile issue in Colorado after two inmates died, in Adams and Jefferson counties’ jails, while in the throes of opioid withdrawal. It’s hard to die from those withdrawals, Valuck said — very hard. But Jennifer Lobato died from cardiac arrest from excessive vomiting. Tyler Tabor died after being denied intravenous fluids.

Both counties paid seven-figure settlements to the families. Jefferson County now has a MAT program. Adams County is the largest county in Colorado, by population, that doesn’t offer one.

Conner, who began working for the Boulder County Jail in 2019 as it was launching its MAT program, called jails across the state to get more information from them. Many were open to it. Few were doing it.

Advocates encountered what they say was an old-school way of thinking — that addicts made choices and must live with them, that providing methadone or Suboxone was simply replacing one addiction with another. But that way of thinking and the forced abstinence it levies upon addicts in jails can be fatal, experts said.

“There’s a battle for the soul of addiction treatment and opioid use disorder,” said Don Stader, an emergency and addiction medicine doctor at Denver’s Swedish Medical Center. “… Abstinence only — it kills a lot of people because people go there, they get help for X amount of weeks or months, they come out, they use and die.”

Several experts, including Terri Hurst, the policy coordinator for the Colorado Criminal Justice Reform Coalition, said not providing MAT to inmates who need it is tantamount to denying them medical care for any other condition. You wouldn’t withhold insulin from diabetics, Valuck said.

Indeed, the U.S. Department of Justice found earlier this year that a New Jersey jail had “acted with deliberate indifference to inmates’ serious medical needs by categorically denying MAT to inmates with Opioid Use Disorder.” That indifference, the agency wrote, led to several inmates’ death by suicide.

Gradually, as jails in Denver, Boulder and Arapahoe counties adopted MAT, others followed suit. Sheriffs who’ve implemented it and spoken to colleagues has been vital in promoting it, advocates said. The National Sheriffs Association has embraced MAT and released guidelines on implementing it.

Costello said sheriffs were especially receptive when advocates couched MAT as a way to make deputies’ lives easier. Valuck said the savings from MAT is significant — $1 spent on MAT saves $14 in costs to Medicaid and correctional costs. There was also a legal question: Would not offering it prompt lawsuits?

“To not do (MAT) seems quite akin to cruel and unusual punishment, that you would not offer this,” said Lt. Staci Shaffer, who in her role in the Larimer County Sheriff’s Office works in the jail and with the MAT program there.

Thirty-four of Colorado’s 64 counties have MAT in their jails, according to a list provided by the state behavioral health office. Depending on whom you ask, that’s either encouraging progress or frustratingly limited.

The program was launched in Denver County in 2018, said Valencia Peterson, a physician assistant who works in the jail. It’s unique because of its relationship with Denver Health, where inmates in the program are referred upon release. When people enter the jail after sentencing, they can apply to participate in the program if they have a history of opioid or alcohol abuse. Those that meet the criteria will meet with Peterson. If there are other diagnoses, such as depression, other medications may be involved, in addition to Suboxone and Vivitrol, an injectable medication that curbs cravings.

According to data provided by Denver Health, 720 inmates participated in the program between May 2020 and July 2021. Of those, there were “98 individuals with diversion,” which refers to those who give their medication to someone else not in the program.

Diversion is a prominent concern, and a prominent risk, experts say. But it can be mitigated by improved staffing and security. But that, in turn, can cost more money and time. Costello said there’s been “tightening” in some programs to prevent diversion, but he added that no jail has started a MAT program and ended it. Peterson said Denver plans to keep up its program and that the “numbers speak to that as well. We know MAT’s important.”

The National Sheriff’s Association in 2017 wrote a brief promoting MAT’s role in reducing recidivism, though research is limited. In Arapahoe County, which started its MAT program shortly after Denver, officials studied recidivism among four groups: Drug users who participated in MAT, drug users generally, opioid users generally, and the entire jail population. Recidivism for MAT participants was 28.5% between 2017 and 2019. For other drug and opioid users, it was more than 60%.

Roughly 79% of Colorado’s residents live in counties where the jail supports MAT, including El Paso County and most of the metro area. In 2019, El Paso County received $150,000 additional funding to help expand its program.

There are notable holdouts: Several advocates mentioned Weld County. It’s not for lack of available services: Providers in Larimer and Weld counties have formed CO SLAW, that is, Colorado Opioid Synergy — Larimer and Weld, a coordinated group of MAT clinics in the counties. One expert pointed out that there’s a MAT clinic across the street from the Weld County jail.

Weld County Sheriff’s Lt. Matt Elbe, who works in the jail, said diversion was a serious concern and barrier for the agency instituting MAT. He said the jail dealt with the medical symptoms of withdrawal and referred patients with substance use issues to resources in the area when released. The jail may institute it at some point in the future, he said, either of its own initiative or because of a state requirement.

Larimer County Sheriff Justin Smith is heavily involved with both the County Sheriffs of Colorado and the National Sheriffs Association. He pointed out that the “overwhelming majority” of counties that don’t have MAT programs in their jails are rural. Indeed, in Colorado, the eight least-populated don’t, and only six of the smallest 20 offer it.

Many don’t have adequate health infrastructure, he said, and their jails are small — he pointed to Jackson County, which has two cells in its facility. That’s one reason, he said, why sheriffs pushed back on legislation two years ago that would’ve required MAT in jails; it was amended to say that jails only had to have a policy addressing whether they had it or not.

“There’s still controversy throughout the community, even the provider community, about things like methadone because it’s a lighter version of what somebody’s already addicted to,” Smith said. “A facility understandably has concerns about contraband and abuse of MAT protocols and systems. That’s been a significant discussion item in our office. The program has been good for us. But there are some legitimate questions that need to be answered. With that, there’s also some resistance from certain sheriffs, I’m sure there is.”

A MAT provider, a clinic, mobile van, individual provider or telemedicine service, is available in all but two Colorado counties, according to the state. A spokeswoman for the state Department of Human Services said in an email that in some “jails in rural communities, (the Office of Behavioral Health) is exploring partnerships to deliver MAT through the (mobile units).”

John Trolley and his girlfriend both entered recovery at the same time last year, after his drug use spiraled and derailed his competitive skiing career.

Brittany’s death is, in part, a story of the absence of MAT. John Trolley’s is a story of its presence.

A Philadelphia native, Trolley’s parents used to send him up to Vermont to ski every Friday, to keep him out of trouble. He started at 12, and by 16, he was competing. He’d ski moguls, and after he moved to Colorado to further his career at 18, he picked up big mountain skiing. He lived in Steamboat Springs and lived as a ski bum, working for resorts and skiing all winter, then following the rock band Widespread Panic in the summer.

In Steamboat, he’d started using party drugs, ecstasy and cocaine, primarily. That continued when he traveled with the band, “a party year-round.” Then he got $3,000 worth of dental work done, and the dentist gave him 150 Percocets in one month.

“I was eating them like candy,” Trolley says.

From there, a friend of a friend introduced him to someone who was heavy into pills. Trolley didn’t realize he had developed a problem until he tried to stop.

He went into rehab but then moved back to Steamboat. Eventually, he developed a cocaine and heroin addiction that cost him as much as $1,500 a day. He stopped competing in skiing: At his last event, he took the place of a friend who’d died in an avalanche.

“I went there to represent on his behalf, but my problem had gotten so bad, I just blew that,” Trolley says. “That was basically the way my whole competitive career went: I’d reach new heights, then my drug problem would bring me back down.”

He was arrested in January 2020, after police found drugs and money in his home. Before being sentenced, he entered New Beginnings Recovery Center in Littleton. He was arrested on a Tuesday, and by the following Monday, he had started Suboxone. That September, he pled guilty and was sent to the Routt County Jail, which has an MAT program. Without that program, “I would’ve been screwed,” he says.

Brittany Medlin became a tragic story. Trolley knew many others. The man — a kid, he calls him — who Trolley bought his pills from overdosed on pills filled with fentanyl. Another kid he met in rehab relapsed and died, also from fentanyl.

But he met another man, another kid, in Trolley’s telling, in Narcotics Anonymous in Steamboat. They were locked up together, and the kid entered the MAT program there. Trolley told him about New Beginnings, about his story and slow road to recovery. The kid’s there now. He, like Trolley, has a chance.

This content was originally published here.