College student Nohemi Salas is a self-described minimalist. In the house she shares with her parents and two siblings, she keeps her bedroom simple. There’s a bluish-gray accent wall with no photos, a bed, desk and a potted plant hanging from the ceiling.

“If I have too many things in my room, then it looks crowded and I can’t concentrate. It’s just hard to focus,” she said.

Salas has had to really focus over the past two years. Until recently, the 22-year-old worked full time as a dental assistant, while taking classes part time at Front Range Community College, in Westminster, Colorado. She was born in Mexico and is a DACA recipient, also known as the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program.

Less than half a million undocumented students are enrolled in college and make up about 2% of all higher education students. One of the biggest barriers to attending and finishing college is money. This group, which includes Salas, is not eligible for federal financial aid.

“One of the reasons why I was working full time is because I needed to pay for my tuition. … I didn’t think there [were] other options for me to pay for college. I just always felt like I had to do both.”

“One of the reasons why I was working full time is because I needed to pay for my tuition,” she said. “I didn’t think there [were] other options for me to pay for college. I just always felt like I had to do both.”

Colorado is one of at least seven states that provide financial aid to undocumented students. To be eligible, a person must meet several qualifications, like attending a Colorado high school for three years before graduating. Under a 2019 state law, these students have access to money to help with tuition, books and housing.

“We’re trying to remove the obstacles to having all of our students get the education that they need, and that we need as a state for them to get.”

“We’re trying to remove the obstacles to having all of our students get the education that they need, and that we need as a state for them to get,” said Angie Paccione, executive director of the Colorado Department of Higher Education.

Last October, the state started accepting applications, and so far, 1,700 students have applied. But Paccione said her office doesn’t know yet how many of them have been approved.

“If you apply for, and you received, all of that aid, then you should be able to graduate,” she said.

This is important because jobs in Colorado, and across the country, are changing.

By 2025, 60% of Americans between the ages of 25 and 64 will need college degrees, industry certificates or other credentials to meet demand, according to Lumina, a national foundation. Nationwide, students of color, including Hispanics and Latinos have a much lower college completion rate than their white peers.

Colorado’s attainment gap is one of the highest in the country, which Paccione and her department are actively working to change.

“If we give them the opportunity to succeed, then they will succeed in our state and they will be tax-paying citizens,” she said. “They will contribute in great ways to the economic needs of the state and to their own personal fulfillment.”

This option wasn’t available for Marissa Molina, who grew up undocumented in Colorado. She started college before there was DACA or any financial help. She was even classified as an international student and paid nearly double in tuition and fees.

“I actually almost dropped out of college my sophomore year because my parents, as you can imagine, paying $10,000 a year, $11,000 a year cash was a really hard thing for my family to do.”

“I actually almost dropped out of college my sophomore year because my parents, as you can imagine, paying $10,000 a year, $11,000 a year cash was a really hard thing for my family to do,” she said.

In 2012, President Barack Obama signed DACA, which allowed Molina to take out a private student loan her junior year. As a senior, she received enough scholarships to cover tuition.

It worked out for Molina; she paid off her loan and is a US permanent resident. Now, she’s the Colorado state director for FWD.us, a bipartisan political advocacy organization that works to reform the immigration and criminal justice systems.

“I think the state of Colorado has also sent a message to students about the importance that they have,” she said. “That they matter, that they’re seen, that we want them to succeed in our state.”

It’s important to get the word out, she continued. Students and families need to know the application is available and safe to fill out.

“So many folks in our community are afraid to share their status out loud, to ask for help, to ask for those resources,” she said.

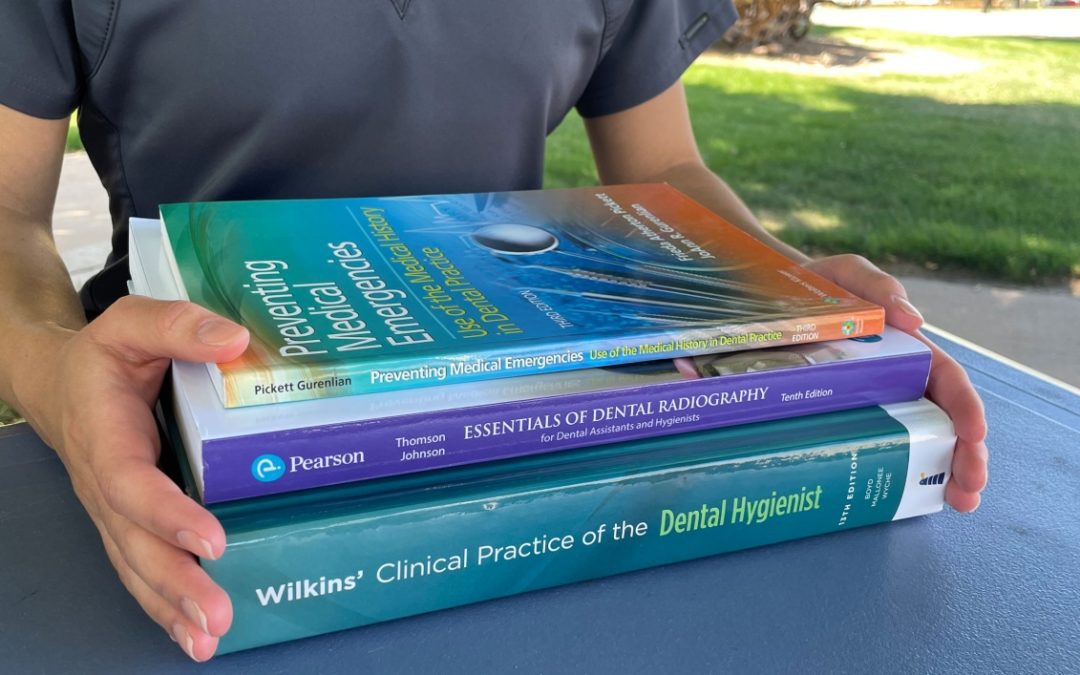

Salas recently started a dental hygienist program at Community College of Denver. During her first week, she attended class wearing gray scrubs and picked up equipment and three textbooks.

“We were going over, like, very basic things, like taking blood pressure, checking pulse, like all that, all that stuff,” she said.

The rigorous two-year program costs about $30,000. Salas applied for state financial aid and received enough scholarships and grants to cover more than two-thirds of her tuition. It was enough money that she could quit her full-time job and become a full-time student.

“It feels weird not to be working. But it’s nice. I feel like I have more time to focus on my studies,” she said.

Salas already has a new study routine. She goes into her room, shuts the door and makes sure her desk is empty. Then she puts down her laptop and opens a textbook, the “Clinical Practice of the Dental Hygienist,” to the first section.

Now, she’s ready to get to work.

This content was originally published here.