Colorado Marijuana Product Potency: Just Another Herbal Medicine

Since the beginning of the year, I’ve been watching Colorado’s burgeoning legal marijuana economy both as a natural products pharmacologist and science and health journalist and writing professor. And while the Colorado and Washington experiments are interesting to observe from afar, I’m amazed, but not surprised, by how much remains the same when it comes to the chemistry of what is essentially a botanical medicine consumer product.

The Denver Post has made a very concerted effort to treat the legal marijuana market as any economically- and culturally-important area of coverage, going so far as to establishing a focused, online publication called The Cannabist.

Over the past week, the section’s editor, Ricardo Baca, has been reporting on an aspect of recreational marijuana products where analytical chemistry reigns – and is putting some companies on the defensive. You won’t be surprised to hear of this episode if you read Bethany Halford’s article on marijuana product testing in the December 9, 2013 issue of C&EN.

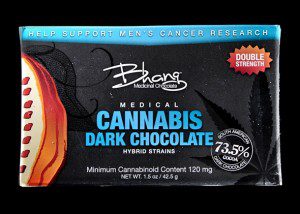

Following a less-than-effective personal experience with an edible marijuana product, Baca wondered whether the amount of THC on product labels truly reflect the abundance of the psychoactive component. In Colorado, marijuana “edibles” – technically called marijuana-infused products, or MIPs – are limited to 100 mg of THC, with a recommendation of 10 mg per serving.

Baca solicited the analytical chemistry assistance of one of three state-sanctioned cannabis laboratories, Steep Hill Halent’s Colorado laboratory, directed by chemist Joseph Evans. One particular brand, Dr. J’s, had several products that tested at less than 1 mg of THC despite being labeled at 100 mg.

This JPG shows some of the other results. Some products did quite well – several were spot on at 100 +/- 6 mg – while others were a bit over.

Baca’s reports were picked up widely this week and, as you might expect, received some pushback from companies whose products didn’t fare that well. But he followed up with some explanations from Evans in this article, as well as some additional replicate testing of products procured from a range of retail sites.

But the companies making these products had better get their act together soon. An editorial in The Denver Post on Wednesday reminded manufacturers that Colorado’s potency labeling standards will go into effect on May 1st.

The variation in active principles in each product reminds me of Consumer Reports‘ herbal quality analyses that I’ve used in pharmacy teaching since back in 1996, where they first showed ginsenoside content of U.S. ginseng products varying by two logs.

Steep Hill Halent also provides other product quality testing that you’d want to see in any botanical medicinal product, including tests for pesticide residues and microbial contamination.

Company CEO David Lampach said in a November interview with Marijuana Business Daily that he expects large analytical firms to ultimately outcompete small testing labs as more states inevitably pass recreational marijuana legislation.

Ana Campoy of The Wall Street Journal had anticipated issues with cannabis potency testing in a report last August. Many of us ACS members are familiar with the longstanding work of Mahmoud ElSohly and colleagues at University of Mississippi’s National Natural Products Research Center in producing and analyzing research grade marijuana. Campoy reported that the clash between federal and state regulation of marijuana excluded well-equipped laboratories like ElSohly’s from testing Colorado and Washington products.

So, companies like Steep Hill Halent have wisely stepped in.

Why bother? Lampach estimates that the U.S. cannabis testing market will reach $40 million by 2016.

Hey, Chemjobber! Should we be encouraging our chemistry followers to get some training in cannabinoid analysis?

This content was originally published here.