The oil and gas industry’s opposition to proposed 2,000-foot well setbacks is heating up, prompting more than 180 companies to send a letter Friday to Gov. Jared Polis that said the rule’s impacts would undermine the industry’s economic recovery.

The leaders of two of the state’s largest industry associations held a news briefing during which they said the proposal by the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission is driven by politics instead of data, science and facts and, if approved, will significantly limit where companies can drill.

“What we’ve said from the beginning is that what we really sorely need for this industry in Colorado is some clarity and some certainty, and we feel at this point neither of those has been achieved,” said Lynn Granger, executive director of the American Petroleum Institute-Colorado.

Granger and Dan Haley, CEO and executive director of the Colorado Oil and Gas Association, said their organizations have spent “hundreds of hours” talking to regulators and other interest groups to try to find solutions.

“A courtroom is always our last resort at COGA,” Haley said. “That said, I think everything’s on the table in order to protect our private property rights and continue to operate in a responsible manner.”

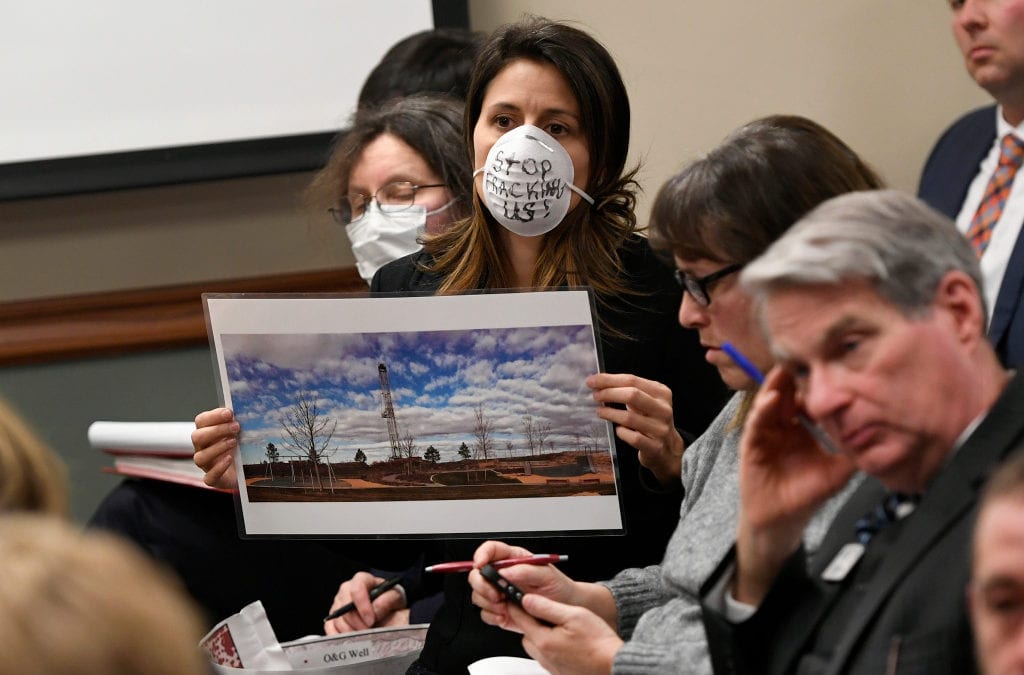

The proposal on setbacks is just one of several being considered by the COGCC as it implements Senate Bill 181, a 2019 law that mandates revamping regulations to prioritize public health, safety and the environment. However, setbacks, or how far well sites must be from homes and schools, have become a flashpoint as drilling has increased and moved closer to populated areas.

The COGCC staff’s initial proposal called for 500-foot setbacks from nine or fewer residences, 1,500-foot setbacks from more than 10 residences and 2,000 feet from schools. After a majority of the commission voiced support for 2,000-foot setbacks, the staff recommended the larger buffer with the possibility of shortening it to 500 feet from homes under certain conditions.

Members of the Denver Petroleum Club wrote in a letter to Polis that the 2,000-foot setback “stands in stark contrast to scientific objectivity” and that the industry hopes his “leadership and calls for a balanced approach to industry regulation will be heeded.”

The League of Oil and Gas Impacted Coloradans had hoped the commission would make the setbacks 2,500 feet, said Sara Loflin, the organization’s executive director. “But 2,000 feet is a remarkably long way from 500 feet.”

Despite the industry’s assertions that science doesn’t support larger setbacks, Loflin said there’s mounting evidence that the closer people are to oil and gas well sites, the greater the chance is they will suffer health problems.

Proponents and opponents of larger setbacks have both cited health studies and reports to support their cases. Broomfield officials have said they have received hundreds of complaints of headaches, nose bleeds, eye and throat irritation and other ailments from people living near well sites.

“I think that it’s important that if we’re going to develop anywhere near people that we’re doing it at a very high standard, which I believe our operators are doing today,” said Haley.

In a call with reporters Friday, Haley said setbacks are just one “tool in the safety tool box” to protect public health, safety and the environment. He noted that the COGCC is strengthening requirements for a well’s structural integrity and management of underground oil and gas lines.

Granger and Haley both pointed to the fact that Colorado voters rejected a ballot measure in 2018 that would have imposed 2,500-foot setbacks from occupied buildings and waterways. They said a COGCC analysis showed that setbacks of that size would have made 85% of non-federal land off-limits to drilling.

This content was originally published here.