Editor’s note: This July, as Colorado Springs gears up for its 150th birthday on the 31st, The Gazette has prepared a series of articles on the history of our city. Check back for fascinating glimpses into the people and events that have shaped Colorado Springs into the landmark it is today.

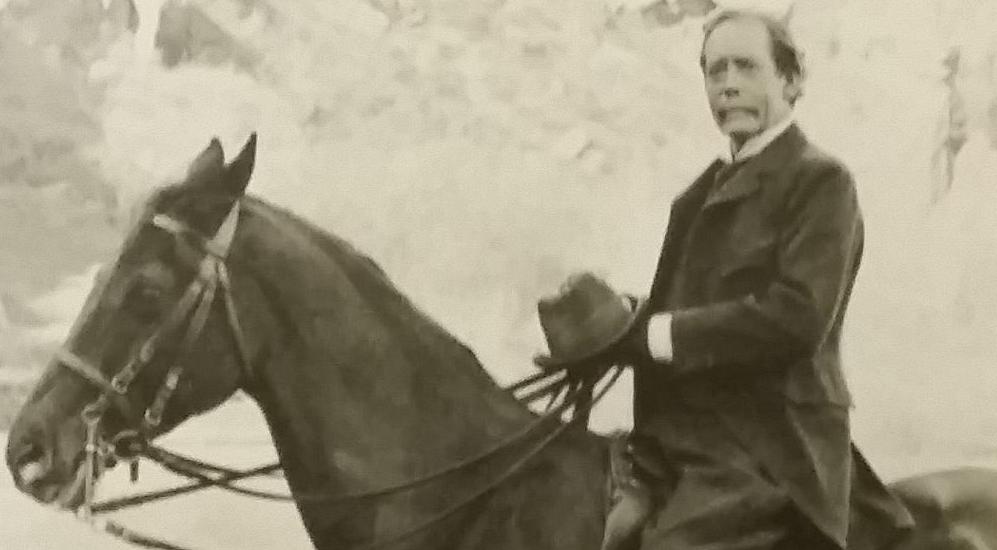

Brig. Gen. William Palmer looms large in the minds of some Colorado Springs residents as a visionary who laid the foundation for the town. But his dreams and railroad took money to build, and while many communities in the state felt his influence, not all remember a philanthropist.

“To know him for what he did only in this city is not to know him. … His influence, good and bad, extends throughout the state,” said Leah Davis Witherow, curator of history at the Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum.

Palmer was an idealist with a grand vision for Colorado Springs to grow into a health resort in the middle of a barren shortgrass prairie, and for a railroad that would run from Denver to El Paso, Texas, and then to Mexico City, but he had no personal fortune to help build it.

He was from a middle-class Quaker family that relied on him for support starting as a teenager. A gifted student, he got a strong start in the railway business working for J. Edgar Thompson, the president of Pennsylvania Railroad, one of the largest and most prosperous railways.

After fighting in the Civil War and striking out on his own in business, he had to travel extensively with his friend Dr. William Bell, founder of Manitou Springs, to find investors on the East Coast and in Europe. He set up numerous businesses to run real estate sales, coal mines and the steel mill in Pueblo to supply rail for the railroad, among other enterprises. At least a dozen of his fellow veterans from the Civil War came out to help with management, Witherow said.

The businesses funneled money into each other to help build the railroad at a time when southern Colorado was sparsely populated and wasn’t seeing the rapid growth that Palmer needed or envisioned, Witherow said.

He also didn’t have many large outside customers to support his enterprises in the beginning and faced several recessions.

“He is idealistic about profits. He’s idealist about markets,” Witherow said.

To support his railroad, Palmer employed some of the ruthless methods of other railroad companies to raise funds.

For example, the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad told Pueblo that it planned to bypass the town on its way west to Cañon City unless the residents sold $100,000 in bonds to help fund the railroad construction. As the railroad neared Pueblo, the company came back for another $50,000, according to an article in The Pueblo Lore by Peggy Runco Willcox.

Then instead of stopping in Pueblo, Palmer bought 48,000 acres and set up a new town across the Arkansas River and called it South Pueblo, a community that was later annexed into the larger town.

“There were some negative feelings for decades,” Runco Willcox said.

Some of the simmering anger is apparent in an 1873 story that ran in the Colorado Daily Chieftain after the Denver and Rio Grande failed to build a train depot a year after arriving in town: “We don’t think our people deserve such treatment at the hands of the company. At Colorado Springs, the company have (sic) provided a comfortable room for passengers. Why not here? This is but one of the grievances we have heard our people complain of.”

This 1889 photograph shows a view of the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad Depot in Colorado Springs. The sign at the left side of the station reads: “This Space Reserved for Colorado Springs Transfer Co.” Brig. Gen. William Palmer founded the railroad and later lost control of the company.

The Denver and Rio Grande went on to set up new towns outside of Cañon City, Trinidad, Salida and Animas City, which we now know as Durango, the town set up by the railroad.

Perhaps the most obvious community that didn’t get rail service was Old Colorado City, founded much earlier in 1859 and the first capital of the territory.

Palmer didn’t want to serve existing communities because the land around the new rail stops needed to be sold to businesses and residents to fund the extension of the railroad, Witherow said. Congressional subsidies to support the railroads were ended because of rampant corruption before Palmer started building, and he didn’t have low-interest loans or land grants other railroads had enjoyed, she said.

“Money is a near constant struggle for Gen. Palmer,” Witherow said.

Then his railroad faced stiff competition when the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad arrived in southern Colorado and the two battled for the path west to Leadville’s silver mines through the Royal Gorge.

The intense extended conflict from 1878 through 1880, known as the Royal Gorge War, devolved into violence several times, including when Denver and Rio Grande crews retook the railway by force following a court decision granting them control, according to the Royal Gorge Route Railroad.

While the Denver and Rio Grande won the Royal Gorge, it lost Raton Pass to the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad and Palmer had to abandon his dream of connecting to El Paso.

Underwhelming profits also made him vulnerable to a takeover and in 1883 he lost control of the Denver and Rio Grande, Witherow said.

The early days of the steel mill in Pueblo that Palmer founded were also tough and workers slept in shacks or on the ground because there was no housing, said Victoria Miller, curator of the Steelworks Center of the West.

The company later blossomed into the largest employer in the state after Palmer’s competitor John Osgood took it over. For a time, the belching smoke stacks helped promote the town as a symbol of wealth, Runco Wilcox said.

One of his later endeavors, the Denver and Rio Grande Western railroad, formed in 1881, connected to Salt Lake and mines in Utah and made Palmer’s fortune.

“There is really a purpose instead of a dream. … His idealism got in the way of being successful with his first couple enterprises,” Witherow said.

Colorado Springs founder General William Jackson Palmer’s downtown statue receives conservation maintenance and a fresh coat of

wax by conservators Frank Lucero and Alison Leard, with Pacific Coast Conservation, on

June 19

.

He also came to regret some of his business decisions, writing to his wife that the market was so competitive it compelled men to do dishonest things and he was ashamed of some actions, she said.

“He always was holding himself up and questioning his decisions,” she said.

In his retirement, Palmer built on his initial vision for Colorado Springs to be a place that nurtures physical and spiritual health by donating many additional acres of parkland to the citizens.

Those land gifts showed that he could be both an industrialist who thought the West was open for the taking and a conservationist, just as he was a Quaker who followed his conscience and fought in the Civil War because he felt slavery was a larger evil than armed conflict.

“He is a study in contrasts,” Witherow said.

This content was originally published here.