By a landslide, Colorado voters decided in 2018 to overhaul the state’s once-a-decade redistricting process. The goal: finally putting an end to the partisan bloodsport known as gerrymandering.

Now, the responsibility falls on the same voters to ensure that the reforms work as planned.

OUR UNDERWRITERS SUPPORT JOURNALISM. BECOME ONE.

This month, the state began accepting applications to serve on the new independent commissions tasked with approving the legislative maps for Congress and the Colorado General Assembly. And in a significant break from decades past, the two major parties won’t have much of a say in who gets chosen.

The hope is that the revamped process will lead to “regular people choosing their politicians rather than politicians choosing their people, says Amanda Gonzalez, executive director of Colorado Common Cause, a group that advocates for government accountability, “You don’t have the people who are trying to gain power drawing the maps.”

Kent Thiry, the former DaVita CEO and a major proponent of Amendment Y and Z in 2018, the measures that created the commissions, said Colorado voters were “fed up with the games, the gridlock, and the partisanship of politics.”

“That’s why we ended partisan gerrymandering — the process that determines how our democracy operates,” he added.

Already, a few dozen people have applied. The group includes people that have no political experience, such as teachers and small business owners, and some who do, like former campaign workers, activists and retired local officials. The legislature’s redistricting staff anticipates upwards of a thousand more will apply by the Nov. 10 deadline.

The public’s role won’t end there. For the reforms to work as intended, officials say the public’s input will be essential throughout the process to make sure the commissioners hear from everyday Coloradans during the deliberations, and not just political partisans, who will be sure to make their own preferences known.

The stakes this year are even higher than usual: Colorado’s expected to gain a Congressional seat at the conclusion of the 2020 census because of population growth. And the new district could reshape the existing districts, too.

Here’s how the new redistricting process will work from start to finish, and the role that you have to play in the map-making effort.

First, a little history lesson on Colorado’s gerrymandered past

Gerrymandering is the practice of drawing legislative lines to benefit the political party in power and dates back to a Massachusetts governor named Gerry, who helped create a sprawling monstrosity of a district that a cartoonist famously lampooned by turning it into a salamander. Some 200 years later, the gerrymander has become a dubious fixture of the American electoral system, tilting Congress, state legislatures and even city councils in favor of one party or another for a decade at a time.

Following the last census in 2010, Republicans controlled more state legislatures than Democrats did, giving them the upper hand in redistricting fights across the country. Gerrymandered maps delivered the GOP as many as 22 additional seats in the U.S. House of Representatives, according to a 2016 Associated Press analysis.

In Colorado, a partisan split in the state legislature approved the congressional map, resulting in a bipartisan accord. But the state legislative boundaries were handled by a politically appointed commission. It put forward a Democratic-backed map that was later affirmed by the state Supreme Court. And, just as Republicans complained at the time, the map has been to the Democrats’ political benefit. In 2016, for instance, Democrats won a majority of state House seats despite winning fewer statewide votes than Republicans, the AP analysis found.

It was also the third time in four census cycles that Colorado’s redistricting process culminated in partisan accusations and a bitter court battle.

How the new independent commissions will be chosen

This time around, gerrymandering opponents are putting their faith in two new commissions that are designed to dilute the influence of the two major parties.

The separate new 12-member commissions are tasked with approving the legislative and congressional maps. The membership is divided evenly among the state’s three largest voting blocks, with four registered Republicans, four registered Democrats and four unaffiliated voters. The final map can only be adopted by an eight-vote supermajority, and at least two unaffiliated votes are required for approval.

It stands in stark contrast with the prior politically appointed system where as many as six from a single party could serve on the 11-member legislative commission. The past method also allowed the maps to be adopted by a simple majority, clearing the way for gerrymandered districts to pass with partisan approval. And if one party controlled the governor’s office and both legislative chambers, as they do now, congressional gerrymandering also was possible.

Here’s how the 12 members will be chosen under the new system:

First, the chief justice of the state Supreme Court will assemble a panel of six former judges who retired from either the Supreme Court or the Court of Appeals. The judicial panel will randomly select applications from 300 Democrats, 300 Republicans, and 450 unaffiliated voters for consideration for each commission. If fewer than that apply and are qualified, the pool will be kept as large as possible. The judges will then review the list and narrow it down to 50 in each category.

Two Republicans, two Democrats and two unaffiliated candidates will be chosen by the judicial panel from the pools of 50.

Then, the top four state lawmakers — two from each party — will each submit a list of 10 candidates they prefer from the initial pool of applicants. The judicial panel will choose one from each lawmaker’s list, adding a total of two Republicans and two Democrats to the commission.

The final two unaffiliated commissioners will be pulled from the larger pool of 450.

Who is eligible to serve on the new commissions

Another pivotal change is who gets to serve. With a few exceptions, the application process is open to anyone who has voted in the last two Colorado general elections — 2016 and 2018 — and hasn’t changed their party affiliation (or non-affiliation) for the last five years.

You don’t need political connections to get on the commission. In fact, certain political operatives are automatically disqualified. Recent congressional and state legislative candidates can’t serve on the congressional and legislative commissions, respectively, if they have run for office within the last five years. Their paid staff members can’t serve, either, if the staffer worked for the candidate or their office within the last three years. Registered lobbyists, elected officials and elected party officials above the precinct level also can’t serve for a three-year period after leaving their political position.

What state redistricting officials want to make clear: You don’t need any advanced degrees or map-drawing expertise. But the application does ask that candidates provide a few personal statements, including why they want to serve, what relevant skills they have and how they hope to build consensus with other commission members.

“It should be people that are interested in fair maps and in facilitating that process,” says Gonzalez. “You absolutely don’t need to be somebody who has a Ph.D. in redistricting in order to do this.”

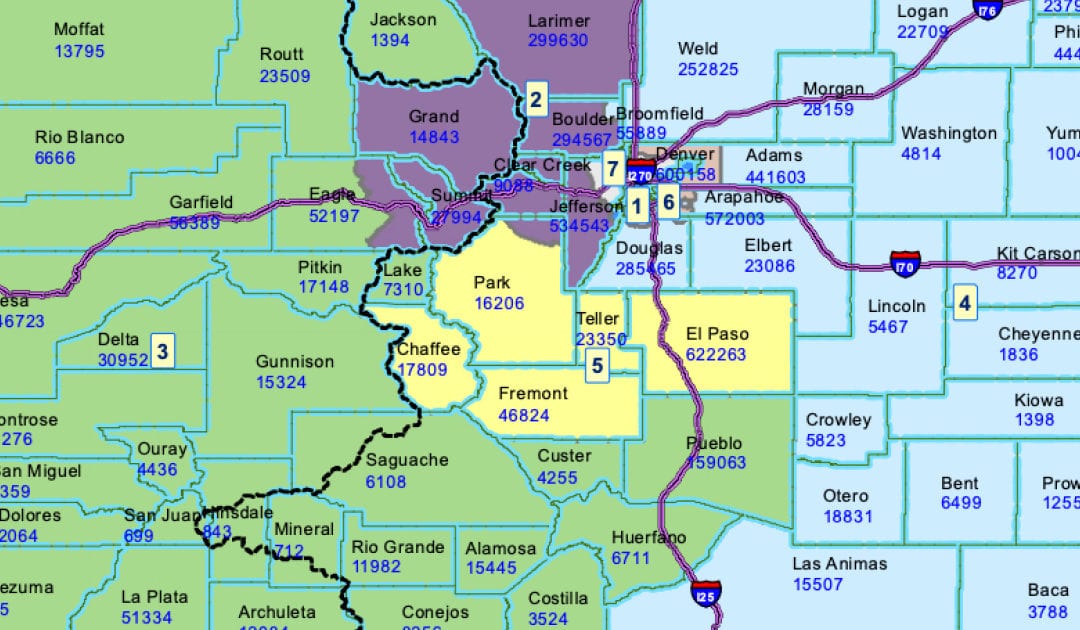

One thing you do need, however, is time. The state’s redistricting staff — a joint effort of Colorado Legislative Council and the Office of Legislative Legal Services — expect there to be four to six meetings in February and March of next year, followed by upwards of 25 meetings in the summer and fall. Many will be held at the state Capitol, but the constitution also requires at least three public hearings in each of the state’s seven congressional districts.

Commissioners will be paid $200 per meeting, plus reimbursement for mileage. All applications are public record, posted on the commission’s website.

How the maps will be drawn — and the role of the commissions

The process will start with a preliminary map drawn by the nonpartisan legislative staff. From there, the commission will hold public hearings across the state to collect community feedback. Then, it can direct the staff to make changes before settling on a final proposal.

In prior years, the staff created preliminary maps as well — but the commission historically ignored them and offered their own maps instead. In a notable change, the new commission is constitutionally prohibited from drawing the map in order to protect an incumbent or give one party an advantage. (That means they can’t draw a line intentionally to include a lawmaker’s house.)

Many of the other criteria they are required to follow are the same as years past. First, districts should be of equal size, to ensure the legal principle of “one person, one vote.” Next, the commission will have to abide by the federal Voting Rights Act, which, among other things, prohibits diluting the voting power of minority groups.

Then, Colorado’s commission is supposed to keep “communities of interest” and political subdivisions, like cities and counties, intact when possible. This is a change from prior cycles, when district lines were supposed to keep cities intact, but not “communities of interest,” a vague term that is up to the interpretation of the commission. Such communities could include people of the same race or culture. It could also mean groups with similar economic interests, like farmers who care deeply about water rights.

The commission also is supposed to make districts compact, to prevent a salamander-style district that stretches from one corner of the state to the other. And finally, the commission must maximize the number of politically competitive districts — all while following all the other criteria.

In other words, redistricting is as much art as science, and fulfilling one goal may require trade-offs from another one. Gonzalez says the commission will need help from the public to ensure the new lines don’t break up communities that have a compelling reason to be grouped together.

“There’s a real opportunity for the public here — and I think a responsibility of the public here — to advocate for their communities,” she said.

The timeline for drawing new maps in Colorado

The application period runs from until Nov. 10, and the commission has to be selected from the applicant pool by Jan. 5.

The governor must formally convene the commissions by March 1. And the federal government must deliver the census numbers by April 1, but often provides them to the state earlier.

The commissions will hold administrative meetings to set policies while the legislative staff prepares its preliminary maps in time to complete the public hearing phase by July 7. But the constitution does allow some leeway for the commission to change the deadline if necessary.

(Due to pandemic-related delays and mounting political pressure from congressional Democrats who are seeking more time to complete the population count, it’s unclear when the census data will be available, which could throw a wrench in the timeline prescribed by voters.)

The deadline to submit the final maps to the state Supreme Court is Sept. 15, 2021.

The court must approve the final map unless it finds that the commission failed to follow the required criteria. And unlike past fights, if the commission can’t come to a consensus, one party can’t ram their map through. A nonpartisan map drawn by legislative staff gets submitted in its place.

The court must approve the congressional map by Dec. 15, 2021, and the legislative map by Dec. 29, to be used beginning with the 2022 elections.

Our articles are free to read, but not free to report

Support local journalism around the state.

Become a member of The Colorado Sun today!

$5/month

$20/month

$100/month

One-time Contribution

The latest from The Sun

This content was originally published here.