New Netflix original docuseries, Conversations with a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes, sheds light on the twisted motivations and brutal methods of the notorious American serial killer. From how Bundy would lure young, female victims to his infamous Volkswagon by faking disabilities and injuries to his jailhouse marriage to one of many female admirers and the daughter that came from it, the series offers no shortage of disturbing revelations. Perhaps one of the saddest is the role a lack of communication between police departments played in enabling Bundy’s 1970s killing spree that spanned four years, seven states and left 30 known victims in its wake.

Fatal Flaw in the System

As detailed in Conversations with a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes, Bundy’s charisma and good looks helped the serial murderer inflitrate upstanding institutions—the Suicide Hotline’s call center, the LDS church—and present himself as a trustworthy young man. One such institution was the headquarters of Washington state’s crime-prevention task force. Bundy volunteered to work with the task force while studying (of all things!) Psychology at the University of Washington.

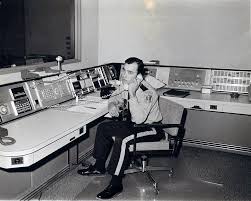

It was the early 1970s. The advent of DNA testing was approximately 20 years away and police relied on eyewitness accounts and line-ups to identify suspected criminals.The term, “serial killer” would not enter the lexicon until 1981. Files were largely paper and precincts did not typically share information with one another. As an Insider article on the case points-out, [the early 1970s] “was a time before even something like fax machines were around to quickly transmit information, let alone email. Instead, most of the time, you picked up a rotary telephone or sent a letter by postal mail.” Bundy noted and exploited these vulnerabilities in standard law enforcement procedure when he embarked on his spree a few years later.

It was the early 1970s. The advent of DNA testing was approximately 20 years away and police relied on eyewitness accounts and line-ups to identify suspected criminals.The term, “serial killer” would not enter the lexicon until 1981. Files were largely paper and precincts did not typically share information with one another. As an Insider article on the case points-out, [the early 1970s] “was a time before even something like fax machines were around to quickly transmit information, let alone email. Instead, most of the time, you picked up a rotary telephone or sent a letter by postal mail.” Bundy noted and exploited these vulnerabilities in standard law enforcement procedure when he embarked on his spree a few years later.

Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing on the Lam

In 1974, Bundy murdered Lynda Healy, a student at the University of Washington. He proceeded to kill Donna Manson, Susan Rancourt, Roberta Parks, Brenda Ball, Georgann Hawkins, Janice Ott and Denise Naslund.

Later that year, Bundy moved to Salt Lake City, Utah to attend law school. In Utah, he murdered an additional four women in their teens and early 20s: Nancy Wilcox, Melissa Smith, Laura Aime and Debby Kent.

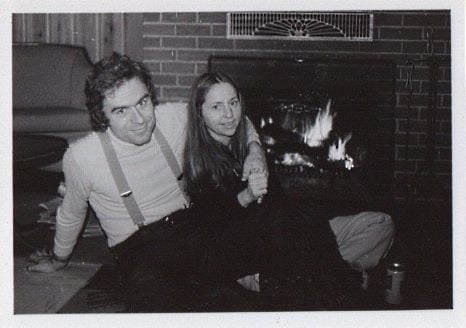

The similarities in the nature of the crimes as well as in the victims’ looks, ages and location led law enforcement to believe that the girls were targeted by the same person. Police called for a number of different government agencies across the Pacific Northwest to join forces and requested the public’s help in searching for the culprit.Four people, including Bundy’s longtime girlfirend, suggested Bundy’s name to police as a suspect.

Bundy’s longtime girlfriend suspected that he was behind the string of murders.

Bundy’s longtime girlfriend suspected that he was behind the string of murders.

Even with suspicion mounting, Bundy was able to flee to Aspen, Colorado, where he committed yet another murder, that of nurse, Caryn Campbell, who was there on a ski vacation with her fiance and his family.

By 1978, Bundy had made his way to Tallahassee, Florida, where he murdered Margaret Bowman, Lisa Levy and Kimberly Leach.

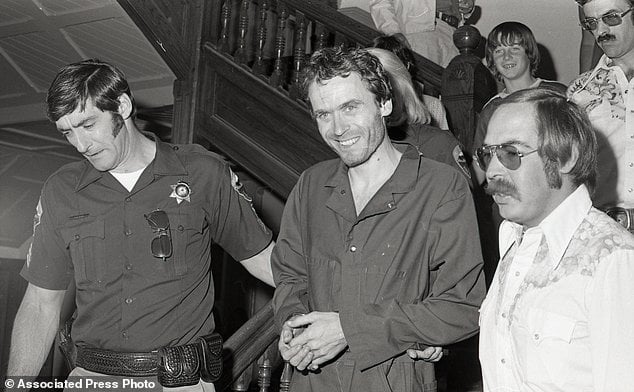

The four year manhunt came to a halt when police pulled Bundy over for reckless driving and found the ID cards of three of his victims in the vehicle. For the Florida homicides, Bundy received three death sentences in two separate trials.He was executed in the electric chair at Florida State Prison on January 24, 1989.

FBI Opens-Up Communication Channels

The length and depravity of Bundy’s murder spree was rehashed for all to see in one of the United States’ first televised trials.This media attention and the emergence of new technology inspired the FBI to create its Violent Criminal Apprehension Program (ViCAP) in 1985.

Local law enforcement officials enter the details of violent crimes into the ViCAP database, which compares them to other cases in an attempt to correlate and match possible connections.The system has played an integral role in solving many cases, even those that are decades old and those that take place in far apart states.

Whereas other local government departments see separate data stores as a costly, time-consuming inconvenience, the Ted Bundy case illustrates how, for the police department, disparate data can mean the difference between life and death.

Source

https://www.govpilot.com/blog/flashback-friday-when-disparate-departmental-data-turned-deadly