A state lawmaker looking to protect fortunes of his Republican caucus as Colorado’s political maps are redrawn this year held a video training earlier this summer to coach people on how to provide testimony intended to keep the incumbent legislators in power after the redistricting cycle.

A video recording of the virtual training held in late July shows a Colorado House Republican telling GOP activists what suggestions they should make in public hearings that will give him and other Republican Western Slope lawmakers the best shot at retaining their seats in 2022.

On the video training, Rep. Matt Soper, a Delta Republican, lamented the fact that the independent redistricting commission system is designed to elicit input from non-political, everyday people talking about their communities, and not from incumbent lawmakers who want to keep a safe seat for themselves.

“It’s been really frustrating because throughout the process,” Soper, who led the training, said, “I’ve heard over and over again, they don’t want to hear from incumbents.”

The state constitution prohibits drawing districts to protect incumbent lawmakers.

But Soper described his plan to try to persuade the independent redistricting commissioners to draw those safe seats by using coached public input from people on the call.

“People like (Rep.) Perry Will, myself, (Rep.) Marc Caitlin, all of us are relying — and even the House Republicans, really — are relying on everyone on this call to make the arguments that we can’t make,” Rep. Soper told people on the virtual training. “We can’t speak. We’ve been muted.”

Soper called on the training participants to attend the commissions’ public input hearings and “advocate for their representatives.”

Soper, along with Former Pitkin County GOP Secretary Maurice Emmer and Mesa County GOP Chair Kevin McCarney, led the public comment coaching, and focused on the preliminary draft maps released by the commissions in June, and what impact they would have on the incumbents if unchanged.

“I was drawn out of my House seat, because I live in Delta,” Soper said. “Perry Will who lives south of Newcastle was also drawn out of his House seat. This is really important for everyone to understand: It’s not just about incumbents, it’s about power on the Western Slope for Republicans in the future.”

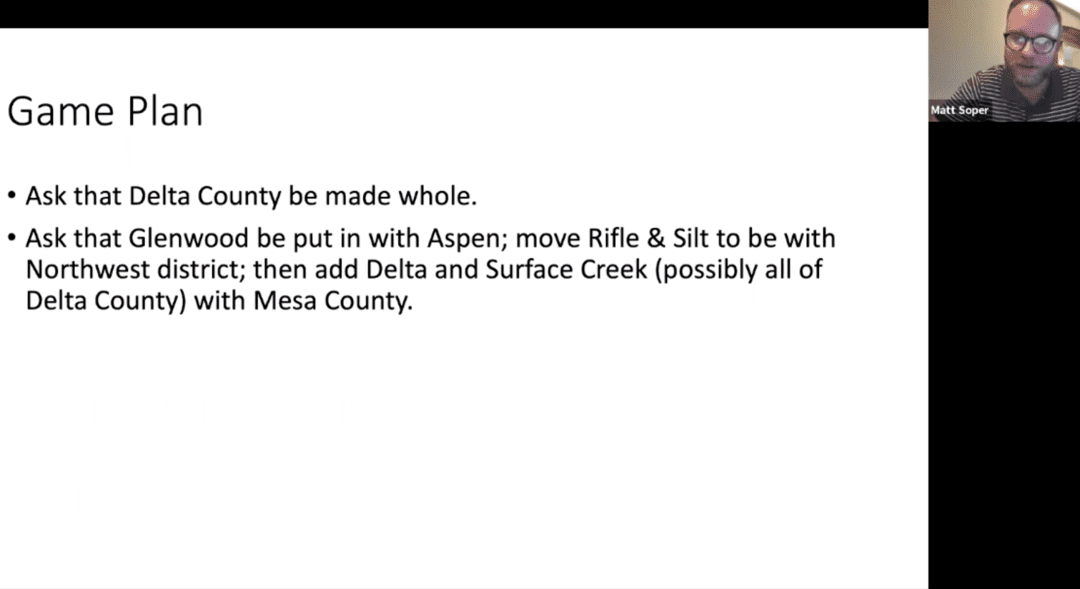

Soper went on to describe the changes to the preliminary draft maps he wanted people on the training to propose during the public input hearings happening around the state. They would move Rifle and Silt into the rural northeastern House District 57, shift Glenwood Springs from the preliminary map’s District 57 into neighboring and Democratic-leaning District 54 and redraw Delta into the southern-neighboring District 53. Soper’s proposal, he estimated, would help keep him and his Republican colleagues from the Western Slope safe.

Soper described specific ways to get to his goal, using roads and highways, wineries, ski resorts, commuter patterns or workforce composition to justify making changes. His proposed arguments would rely on preserving “communities of interest,” which are required by the constitution to be kept whole, in balance with other redistricting criteria.

“I’m just telling this to give you ideas of how to argue and hopefully write a short persuasive speech to send to the commission or testify in person,” Soper said.

McCarney, who was also part of the training, reiterated that those speaking to redistricting commissioners would need to veil their goals.

gazette file The meeting of the state’s independent congressional redistricting commission had few attendees at UCCS on Aug. 5.

“Matt talked about this a little bit, but we can’t say, ‘Hey, put Matt Soper back where he belongs,’ and you can’t say, ‘Hey, put Perry Will back where he belongs,’” McCarney said, “but what you can do is say Western Delta County has been traditionally teamed with Mesa County because of the commonality of agriculture and the rivers and Highway 50.”

Soper emphasized the subterfuge involved: “Do not mention party or incumbents. I cannot stress that enough.”

The recorded video training, which was provided by someone familiar with the redistricting process, but who asked to remain anonymous due to the sensitivity of the issue, puts a spotlight on the transparency requirements built into Colorado’s independent redistricting commissions, which were overwhelmingly approved by voters in 2018.

Soper’s actions aren’t explicitly a violation of the law, but the state constitution, which was amended to create the independent redistricting commission system after the 2018 vote says that any map “drawn for the purpose of protecting one or more incumbent member, or one or ore declared candidates, or the Senate or House of Representatives, or any political party” cannot be enacted, putting the commission a precarious legal position, where public testimony, if followed by the commission, could haunt them later, if it’s revealed that maps were drawn for the prohibited purpose.

Soper wrote in an email responding to questions about the training that nobody was paid to facilitate the video training, and that it was a small number of people.

“I recall there only being about five to six people on the call,” Soper wrote. “The Zoom call group is made up of several conservatives (basically a virtual coffee club) across the West Slope. I was asked if I would talk about redistricting and do not believe it was advertised other than an email to the group.”

Asked what the commissioners should now think about testimony they heard in Western Slope public hearings, Soper said he was trying to coach people about how to talk about communities of interest, and likened his training to “a professor encouraging students” about how to write an article for a journal.

“A redistricting commissioner has to look at the law when making a determination. The law says districts cannot be drawn for incumbents, districts must be communities of interest, compact, and where possible, competitive,” he wrote. “The commission has to determine if citizen comments satisfy what is required by law and whether they choose to listen to comments.”

In a follow-up conversation, Soper said he thinks other lawmakers are doing the same thing: “Anyone who thinks that any single office holder isn’t out talking to people is certainly drawing sheepskin over themselves.”

In the video, Soper also told the training participants that a set of high-profile lobbyists who work for an organization whose donors are secret have been advocating for the GOP lawmakers’ interests, even though the group’s representatives have said they aren’t working for Republicans.

“The Colorado Republican Party, the House Republicans and Senate Republicans hired Alan Philp, Greg Brophy and Frank McNulty to represent our interests,” Soper told the training participants.

Frank McNulty is a former Colorado House Speaker. Greg Brophy is a former Colorado House and Senate member. Alan Philp runs a political consulting firm and is a registered lobbyist for the organization that the three are working under, called Colorado Neighborhood Coalition.

The group is a 501(c)4 “social welfare” organization, which means they can accept unlimited donations whose source never has to be publicly disclosed. When a 501(c)4 organization spends money in elections, it’s called “dark money,” because the financial backers are kept secret.

Philp told The Gazette Soper is just wrong, and that he’s upset that Soper said Colorado Neighborhood Coalition’s efforts were paid to represent Republican interests in redistricting. McNulty also said Soper was incorrect on the payment arrangement.

“It’s just factually incorrect,” Philp said. “I don’t know Matt Soper and I don’t know where he got that. We don’t work for the Republican Party. We don’t work for the House Republicans. We don’t work for the Senate Republicans. We’ve not received any money from them.”

Soper wrote that he now believes the information he passed along about Colorado Neighborhood Coalition is wrong. Under IRS rules, the organization does not have to specify who is funding it.

“I thought Philips, Brophy, and McNulty were representing our caucus and party. This was my misunderstanding,” he wrote. “The GOP is not paying these guys and in fact my frustration has been the lack of support from the state party and the caucus.”

Philp also testified to the commission in July, saying that he was there on behalf of Colorado Neighborhood Coalition, but that he also wasn’t being paid by Republicans.

Colorado requires anyone who is lobbying the redistricting commission to register their activity with the Secretary of State, and the Secretary of State has defined what qualifies as redistricting lobbying: “anyone who is contracted for or receives compensation to communicate directly or indirectly with a member of a redistricting commission, commission staff, or commission contractors for the purpose of aiding or influencing the redistricting commission. Anyone communicating with the commission, their staff, or a contractor on behalf of another party is a Redistricting Commission Lobbyist.” The state elections office further clarifies that volunteer lobbying, or even sending mass emails with suggested talking points about mapping could qualify as lobbying that’s required to be disclosed.

So far, Colorado Neighborhood Coalition has reported paying Philp $2,000 in April for what the disclosure characterized as “communications with commissioners.” Brophy met with redistricting commissioners in May to talk about his experience on the reapportionment committee in 2011, but he didn’t register as a lobbyist, because, he and McNulty have said, Philp is the organization’s registered lobbyist, and they believe that by having a single registered lobbyist who reports the organization’s lobbying efforts, they’ve complied with the lobbying disclosure requirements.

This content was originally published here.