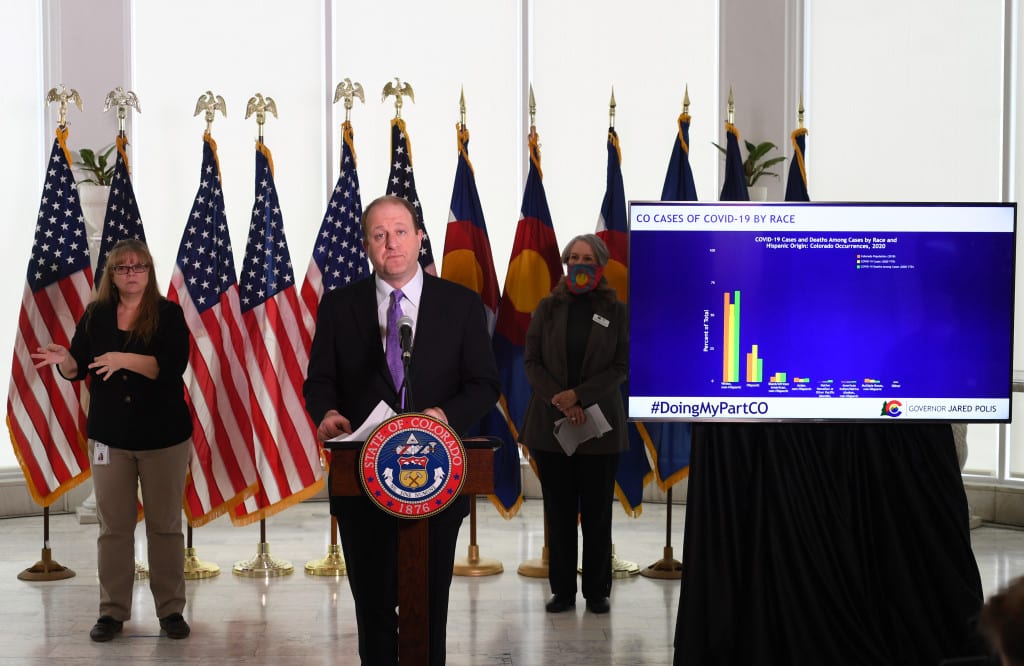

The coronavirus pandemic is spotlighting racial inequalities in Colorado as new data from the state health department shows black residents are dying from the illness at a disproportionately high rate, and people of color in general are seeing elevated infection rates.

COVID-19, the respiratory disease caused by the new coronavirus, is spreading among the state’s black, Hispanic and Hawaiian/Pacific Islander residents at high rates compared to their shares of the population, according to the data released by the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment on Monday.

While Gov. Jared Polis said at a news conference that such racial disparities “could be a proxy for economic disparities,” health experts took a firmer stance, pointing directly to systemic societal and health inequalities as a driver for why the disease is having a heavier impact on people of color in Colorado.

“We know that social and health care inequities affect outcomes, and that becomes even more apparent in times of disaster,” Jill Hunsaker-Ryan, executive director of the state’s health department, said in a statement. “There have been generations of institutionalized barriers to things like preventive medical care, healthy food, safe and stable housing, quality education, reliable transportation and clear air.”

Black Coloradans make up 363 — or about about 7% — of the 5,188 coronavirus cases analyzed by the health department, despite the state’s black population standing at 3.9% of Colorado’s total.

Of the 249 COVID-19 deaths included in the data, 17 fatalities — or about 6.83% of the overall total — are black Coloradans.

The data released by the Department of Public Health and Environment is limited and only represents 75% of all reported COVID-19 cases. Cases with an unknown race or ethnicity are excluded from the data, which also does not include everyone who has become sick with the illness. The number of confirmed cases in the state — 7,691 as of Monday — is significantly lower than the actual number of Coloradans with the disease because of inconsistent testing.

At least 308 people have now died in Colorado in connection with the new coronavirus.

Other data released by the state shows:

“We are all together here as a state,” Polis said during Monday’s news conference. “People live in integrated communities. You can’t say we’re stopping it for Hispanics and not for white people, or for blacks and not white people.”

Data released Monday by the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment shows people of color in Colorado have been disproportionately impacted by the novel coronavirus.

The preliminary statewide data on race reflects nationwide trends and is similar to the way the novel coronavirus is impacting Denver residents. Early data released by Denver Public Health on Friday showed black residents faced higher rates of infection, hospitalization and death than white, Hispanic or Latino residents.

“We know historically that the African-American and Latino communities have been more prone to chronic ailments such as hypertension, high blood pressure, diabetes, asthma, heart disease,” Denver Mayor Michael Hancock said during a news conference Monday. “Because we know that, and we know that this particular virus prays harder and disproportionately on people who have those conditions, it is incumbent on all of us to be even more careful about staying indoors.”

Those underlying health issues cited by Hancock make patients more susceptible to complications, including death, from the novel coronavirus. Black people also are over-represented in service industry jobs and positions that cannot be done remotely, putting them at additional risk for contracting COVID-19.

Dr. Terri Richardson, a physician and vice chair at the Colorado Black Health Collaborative, said Monday that while systemic disparities play a part in the impact of coronavirus on black residents, more specific data is needed to determine exactly what is going on in Colorado and how to counteract it.

“I know most people are saying it’s related to the disinvestment in black communities, longstanding health disparities, a lot of social determinants, or it’s because African-Americans are doing front-facing jobs, bus driving, working at restaurants — these are the types of things you hear,” she said. “But for me, I think that we have to really try to take a deeper dive into this data. Really what is happening?”

She said the state needs to provide specific information on the black patients who are dying from COVID-19 that examines the patients’ risk factors like age, chronic diseases or occupation — details that go beyond solely the patients’ race.

“What are the details of the people dying?” she said. “Did they present and were they in the hospital for five minutes, were they there for 14 days, how did they get it — what are some of the demographics around them, other than they were black? The social determinate issue, the racism, that is all real, but we’ve got to still take that, and the specifics.”

Knowing that information, she said, would allow health officials and organizations to tailor their prevention and education efforts to the particular impacted population, rather than casting a wide net.

Nationwide, there have been calls for public health agencies to release racial and income data related to understand the spread of the new coronavirus and know who is becoming sick with the respiratory illness.

“If we’re not able to see clearly what’s going on in different communities, we’re not going to be able to allocate resources appropriately,” said Dr. Richard Besser, former acting director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and president of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Black residents have been harder hit by the virus in New York, Detroit, Chicago, New Orleans and Milwaukee.

Richardson said the Colorado Black Health Collaborative has focused its efforts so far on countering misinformation about the novel coronavirus and educating residents on when to stay home and when to seek care. Some in the black community, she said, have hesitated to seek health care even when they’re sick.

“There’s been a problem with trust, as well as being empowered in the health care system when it comes to our black populations and other populations of color,” she said.

Others, experts said, simply can’t afford to stay home and social distance.

“So many of the things that we tell people to do to reduce the outbreak on individuals are things that for many people are nonstarters,” Besser said. “Asking people to stay home and social distance to protect themselves and their families and their communities, for millions of people you are asking them to not put food on the table and pay the rent.”

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

This content was originally published here.