Against the dying day, twin sisters Jesse and Tyler Youngwerth decided they would just go for it.

In California that summer of 2012, there was a nude beach and a rock to climb. There were two 20-year-olds who had always loved climbing, who had thought up to that point the sport would be their careers, who starting the next day would learn that life had other plans for them.

The next day, they would be hurtled into a new reality. They would lose whatever this youthful, rebellious innocence was that compelled them to scale that crag all-natural.

“We just tried to live life to the fullest for the last few hours we had,” Jesse recalls.

They were due for a surgery as uncertain as the disease that necessitated it, detected just weeks before at their home in Colorado Springs.

Moyamoya, the Youngwerths learned, was a rare, little-known condition in the brain, afflicting one in a million. The blood vessels progressively narrow, limiting the vital flow. Moyamoya was first described in Japan, translating to “puff of smoke,” because that’s what it looked like on an X-ray: blood ballooning from a match-like artery.

On each side of Jesse’s and Tyler’s brains, a surgeon would reconstruct pathways for the blood, connecting arteries from elsewhere. The sisters remember the procedure, spread out over weeks, as horrifying, something like science fiction: holes drilled around their scalps; fluid that spilled down and tasted like pork; stitches across their swollen heads; IVs up and down; drugs that made their already foggy minds foggier.

“Like a blur,” they both say now, but forever haunting.

“It’s super scary thinking that your best friend and counterpart might not come out,” Tyler says, wiping away tears. “You just hope that you get to see her again. That was hard.”

Initially out of the hospital, they thought to get back on the competitive circuit. But the opposite realization was among trials of life after surgery. A fractured relationship with climbing was at the core of existential upheaval — change that continues today for the sisters, now 28.

“When you’re that young and faced with a life and death situation, it just all of a sudden puts mortality in their eyes,” says their mother, Lisa. “Kids who don’t go through something like that, they just have no way of knowing you could die at any moment. I think it made them more sensitive to that.”

The prognosis came suddenly. In the middle of another climbing competition in Vail, Tyler didn’t feel right. A side of her body was in full revolt, her arm and leg out of control. Her words slurred and face drooped.

“We knew something was seriously wrong,” she says.

She and Jesse both had a stroke the year before, but the family came to believe it was a side effect of a medication they’d taken.

Now they went in for tests. Tyler was diagnosed first.

“Because I wasn’t showing any symptoms, I don’t think it really hit her,” Jesse remembers. “For me, it was terrifying, because my sister had to go get brain surgery. It hit me then.

“And then we went and got my testing done and confirmed. That’s when it hit her.”

They’d always had this emotional connection. Always felt for each other. Always felt joy in the other’s victories and pain in the other’s defeats.

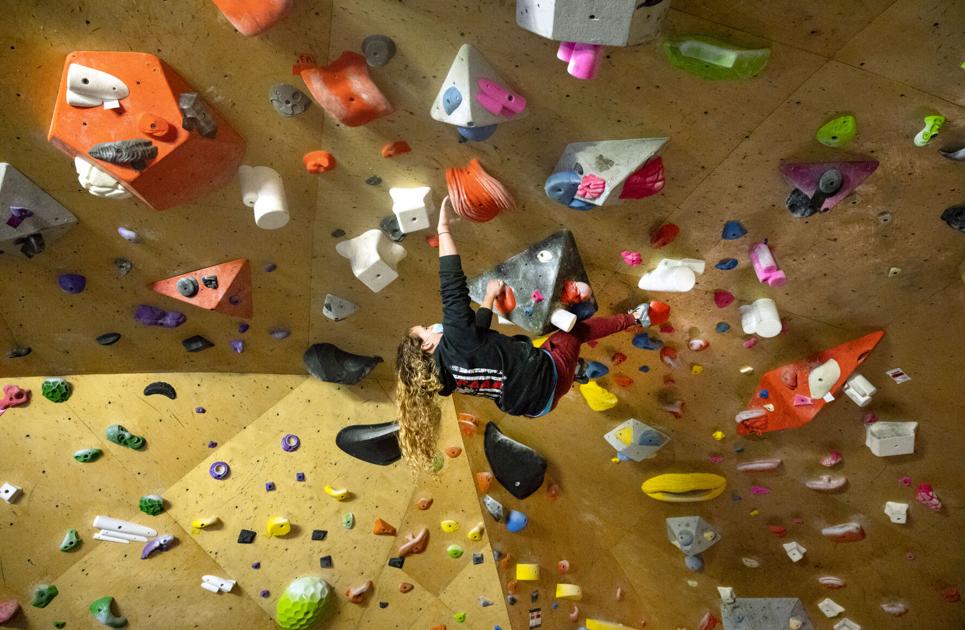

That’s because they intimately knew how hard the other worked. They’d train for hours on end, right beside each other on that climbing wall in the garage, clinging to those holds for 90 minutes straight in a brutal test of endurance.

It paid off at contests around the world. The teenagers rose the ranks, gaining notoriety and sponsors for their prowess and also for their uniqueness. They were the mighty twin climbers.

Then they were the twins with Moyamoya.

In California for surgery, researchers followed and asked questions. “They never saw it in twins before,” Tyler says.

But the twins didn’t feel like answering questions.

Tyler, for reasons that were unclear to her, felt angry. She’d kick and scream. But she felt better with ice cream, and noticing her quiet sister in the bed beside her, she offered her some. Jesse declined.

Tyler got to thinking sunshine was what Jesse needed. And so she rose to her feet and implored Jesse to do the same, and in a scene that caused quite the stir, the two in their gowns walked with their IV stands out to daylight, just for a moment.

“I’m really happy that happened,” Jesse says.

It was a moment breaking the darkness that would prove overwhelming in the months and years ahead.

“I was just in a really bad place where I didn’t think I was real,” Jesse says. “I didn’t think I actually woke up from surgery, and like I was living this kind of different life. It was odd … I felt like I was by myself.”

She tried climbing again. It was always about “the perfect climb,” she says. “Climbing the perfect route, to make it flawless. That was my goal.”

That wasn’t happening anymore. It hit Tyler, too. She felt resentment for her sport.

“I think there was fear, too,” Tyler says. “Probably because I knew that I wasn’t gonna be as strong as I was before, and the judgement that comes with that.”

Climbing remained in the foreground; Tyler and her parents own Gearonimo Sports, the outfitter attached to a climbing gym.

But it’s been just recently that the sisters started climbing regularly together again.

Almost 10 years ago, they were those kids on that California beach. “You need another reminder sometimes,” Tyler says — a reminder to live to the fullest.

That was 2020 for the sisters, marked by many as a year of loss. A year that put things in perspective.

“I realize I don’t necessarily have my sister forever,” Jesse says, “and she doesn’t necessarily have me forever.”

So off she’s gone to join Tyler at a local rock. It’s becoming a weekly tradition now.

And now there’s nothing competitive about it. No need for perfection. No need to fear. Now it’s just about simple joy.

“I just feel warm,” Jesse says. “Like my body feels a glow that I’ve never really noticed before.”

There they are again, rising to meet the sun.

This content was originally published here.