Editor’s note: The Salt Lake Tribune is providing readers free access to critical local stories about the coronavirus during this time of heightened concern. See more coverage . To support journalism like this, please consider or become a .

Salt Lake County crossed two unenviable milestones in the coronavirus pandemic Friday: More than 1,000 cases of COVID-19 have been confirmed in the county, and 10 residents of the county have died.

With each new case, though, comes data that county health officials are using to learn more about how and where the virus spreads, the county’s epidemiologist said.

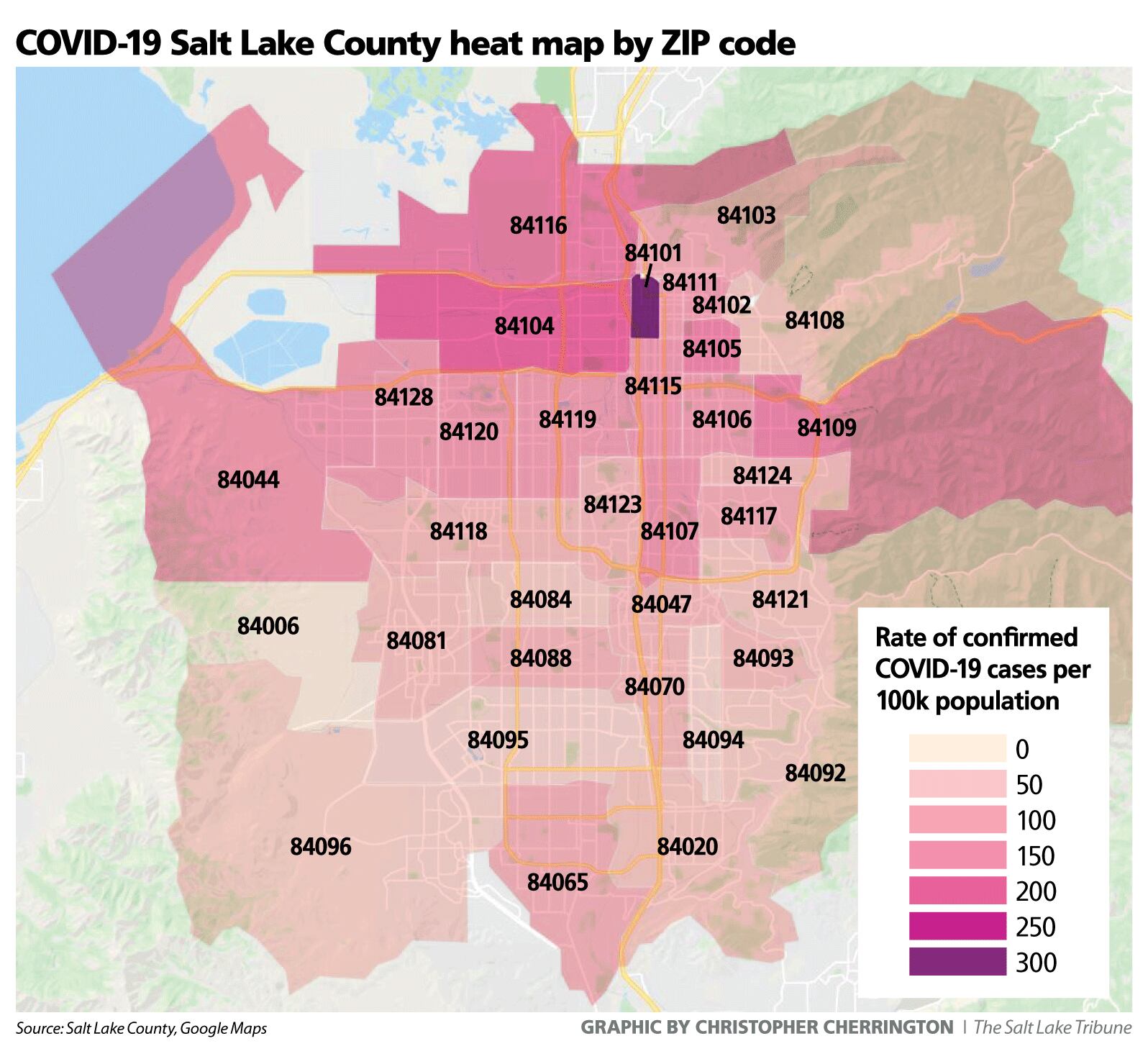

And that data shows the virus is hitting Salt Lake City and the west side far more than east side communities or the cities in the south end of the county.

Statewide, the Utah Department of Health reported Friday that four more people have died, raising the state total to 17. The four were all men over age 60, and all had underlying risk factors that made them more susceptible to COVID-19.

One man was a Utah County resident who died in a hospital. A spokeswoman for the Utah County Health Department had no further details about that case.

The three other men were from Salt Lake County, said Angela Dunn, state epidemiologist. Two were living in long-term care facilities, where they were infected with the coronavirus; the third died in a hospital. The state would not say which day these men died.

Ilene Risk, epidemiologist for the Salt Lake County Health Department, said that six of the 10 county residents who have died were living at long-term care facilities.

Eight of the 10 were over age 60, Risk said. The other two were under 60 but had underlying health issues. (One of them, Silvia Melendez, 24, of West Jordan, died on March 28; she suffered from diabetes and had heart surgery two years earlier.)

According to state figures, updated Friday, Salt Lake County had 1,011 confirmed cases, a bit under half of the state’s total of 2,102 cases. The county has had 92 people hospitalized with the virus; that’s about half of the state total of 183.

The county’s numbers are slightly different, but not by much. According to the county health department’s website, Salt Lake County has had 1,013 cases and 90 hospitalizations since the outbreak began.

Risk’s department recently began posting seven pages of charts and graphs to break down the data by age, gender and ethnicity — as well as by which symptoms have been reported more often. (Coughing leads the pack, with 75%.)

The seventh page features a “heat map” that shows which ZIP codes have the highest per capita infection rates.

The highest level of cases is in 84101, in the heart of downtown Salt Lake City. It has a whopping 315.1 cases per 100,000 population.

That’s a bit of an anomaly, Risk said. That ZIP code only has had 15 cases of coronavirus, but the per capita number is high because only about 4,700 people live there. The area includes a lot of nonresidential real estate: The Gateway shopping center, the west half of the City Creek Center, the Salt Palace Convention Center and much more.

But those who do live in the downtown area, Risk said, are in apartment complexes, which may be a factor in the infection rate. “When people are densely populated, you might have less ability to physically distance,” Risk said.

After that the highest rates are clustered mostly on the west side of the county. The 84104 ZIP code — an area west of Interstate 15 to 7200 West, between I-80 and State Road 201 — has a rate of 188.3 per 100,000. 84116 is north of that, through Glendale and Rose Park to the Great Salt Lake, and has a rate of 157.

“We’re not exactly sure why there’s a predominance” of cases on the west side, Risk said. Socioeconomic differences — the west side is traditionally more working class than the east side — could be part of it, but other factors could also be at play.

Public health officials, Risk said, “try to identify clusters, which might not just be ZIP code but social networks.” Outbreaks — instances where two or more cases pop up in the same place — could be at work sites or in a health care facility, not just in a neighborhood, she said.

The unfortunate paradox of a pandemic is that the more people who get the disease also means public health experts have more to study. “We learn a lot more with a lot more data,” Risk said.

And Dunn, the state epidemiologist, wants to gather even more data.

She put out another call for people with symptoms of the coronavirus to get tested. She encouraged medical providers to help anyone who has a fever, a cough or shortness of breath to get a test. Identifying people who have the virus, even mild cases, will allow public health workers to contact people who have been around those who tested positive.

“This is essential information we need as a public health agency to contain the epidemic here in Utah,” Dunn said.

Utah has been increasing its testing capacity. Early in the pandemic, Dunn and other state officials reserved testing for people with severe symptoms and who were most at risk. Now, she said, anyone with a symptom should be able to get tested.

This content was originally published here.