“Source Material” is the kind of art exhibition that I had been expecting — and wanting — to come along in the late stages of the coronavirus pandemic.

It promises to do all of the things you hope an art show will do: introduce unfamiliar talent, delve into current trends, and provide a bit of high-quality entertainment while asking viewers to look deeply and understand more. The just-opened offering at the Colorado Photographic Arts Center brings together eight artists from the United States, Canada and France, each with their own ideas about what a photo is, how it can be made, and what it can say.

But it’s still an intimate and often very personal assemblage of objects, arriving at a time when we’ve all been looking inward, and it connects gracefully with our lingering need to heal and recover collectively from the emotional stress forced upon us by the on, off and on-again worry that has come to define this global health crisis.

Its theme: Care. Communal care, family care, self-care. All of the artists seem to be attempting to heal old wounds or right long-standing wrongs, to make things better.

If you go

“Source Material” continues through Sept. 25 at the Colorado Photographic Arts Center, 1070 Bannock St. It’s free. Info: 303-837-1341 or cpacphoto.org.

Curators Jon Feinstein and Roula Seikaly, both with New York-based Humble Arts Foundation, chose artists who use found objects as their “source material.” They take items they’ve encountered in one way or another — perhaps in their attics or in archives, or in the trash or thrift shops — and use it as the intellectual base for bigger ideas, giving it a “second life,” as Feinstein described it in an interview last week.

There are as many methods to this as there are artists in the show, which I was able to view digitally in advance of the opening.

Aaron Turner’s “Black Alchemy” series relies on vintage photos of key figures in Black history.

Aaron Turner’s “Black Alchemy” series, for example, starts with photos from his own family’s collection, but then mingles with them images of variously known figures in African-American history, such as Frederick Douglass and Drue King, to create collages that mash together the past and present.

“He’s not just elevating these people, just retrieving them from a long-dead history,” said Seikaly. “He’s also seeking to understand who they were and, through that understanding, further get into his own life, and his experience as a black man living in this country in the 21st century.”

How does reflecting on the way an icon, like Douglass, is viewed and considered today challenge and elevate the contemporary artist’s own view of himself? Clearly, it’s a personal journey for Turner, and he only offers us clues in this work, but there’s a timelessness to the final product. “Shrinking that space between the middle of the 19th century and the 21st century is something photography can do so elegantly,” said Feinstein.

So much of the work here travels through time, often with an aura of redemption or reckoning with past trauma. Jody W. Poorwill’s “Gentle” series adds multiple effects to a kindergarten photo portrait, acknowledging a time when they (Poorwill’s preferred pronoun) were struggling to be visible on their own terms. The images, resurrected and commandeered in Poorwill’s adult life, show that, indeed, the artist found a route to self-expression.

Artist Jody W. Poorwill uses a kindergarten portrait as a starting point in “Source Material.” (Provided by Colorado Photographic Arts Center)

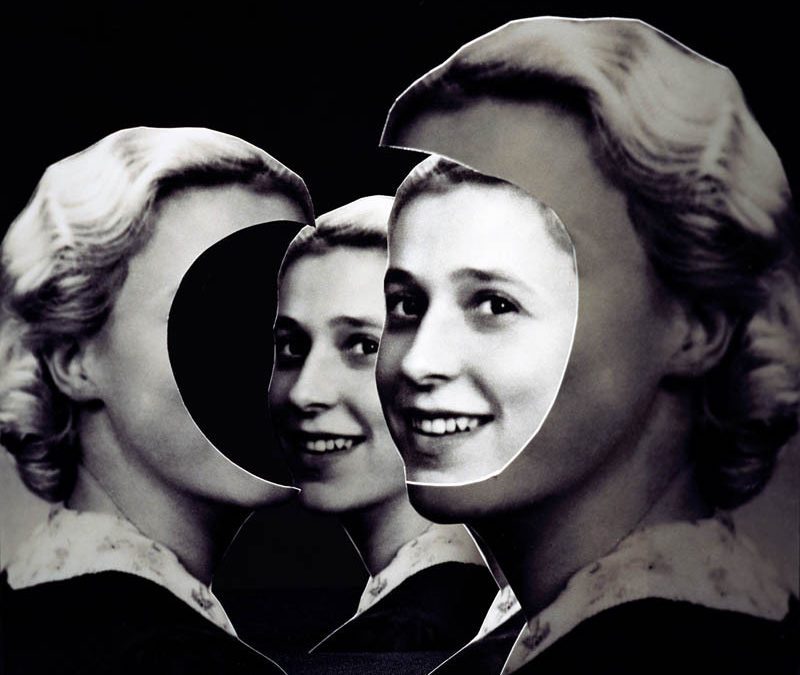

For the series “Her Story,” Birthe Piontek begins with vintage photos of her mother and grandmother, tearing and layering and rephotographing them to explore the women’s struggles with memory loss due to Alzheimer’s disease. The finished objects acknowledge the depth and difficulty of memory skills while also honoring their power and validity.

In much of the work, there is a positive spin on the past, or at least some hopefulness for the future, brought forth.

That sets the objects in this show apart from a lot of art that relies on found objects. Artists long have been using old media as inspiration for new work, of course, but often with a dose of cynicism or contempt for history, or to challenge current thinking.

The curators here were looking for something different. “Found photography and appropriated photography is done, oftentimes, not with sinister intent, but there’s a sort of ghost around it, “ said Feinstein. “This rethinks that through a lens of care.”

He brings up the show’s keyword again — “care” — and that seems appropriate. The work can go to extremes in that regard, sometimes in broad strokes. Pacifico Silano’s “Cowboys Don’t Shoot Straight (Like They Used To)” builds upon images borrowed from 1980s gay pornography to resurrect the spirit and existence of folks gone, and possibly forgotten, at the height of the AIDS epidemic.

Other times, the efforts feel small and amazingly tender. Alayna Pernell begins the process of her “Our Mothers’ Gardens” series with vintage photo portraits of Black women, taken probably in the mid-20th century. Pernell pulled them from various archives where the subjects are anonymous and forgotten.

But Pernell caresses each of the photos personally and lovingly, and reshoots them with her own hands visible in the frame — you actually see her coddling these old images. The resulting photos serve as a sweet tribute to these long-gone women as individuals, a message that their lives mattered.

In truth, the level of care suggested by the work in this exhibition may be more than many of us need or want these days, but all of the series included here — because they tend to flip back and forth so generously between then and now — serve as reminders to look at the big picture.

They suggest we take our present seriously, and to experience both its richness and shortcomings. But also to consider that it doesn’t define us entirely, and that it is never beyond redemption. “Source Material” starts with care but it ends in optimism.

This content was originally published here.