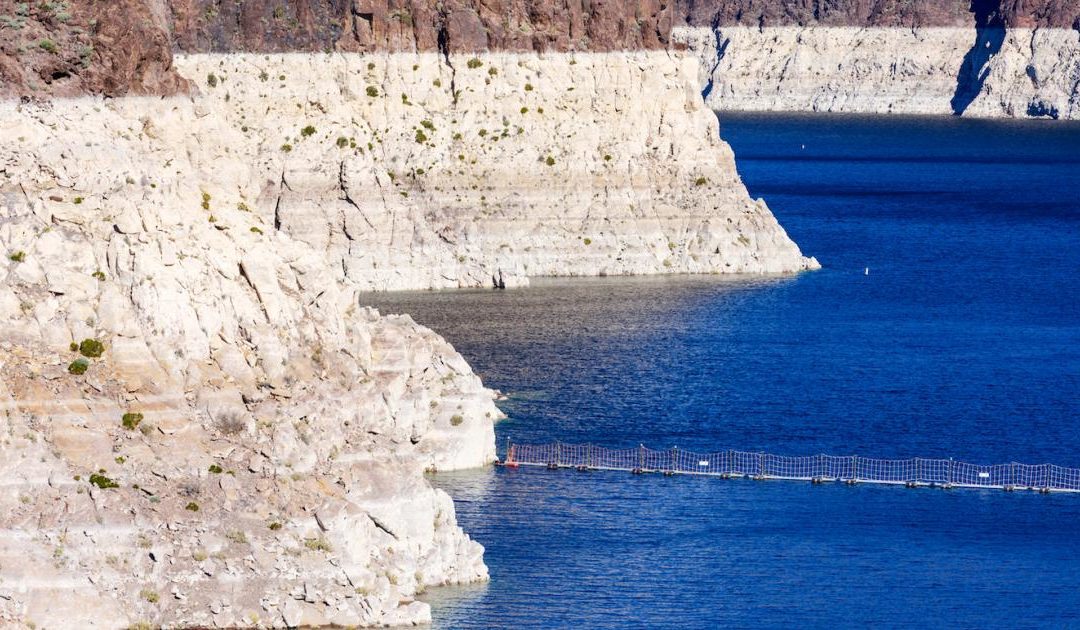

On Aug. 16, the U.S. federal government declared a Colorado River water shortage for the first time. This unprecedented action was triggered by the precipitous drop in Lake Mead’s water level: It’s at 1,067 feet above sea level, or about 35 percent full. The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation expects the lake’s water level to remain about 1,066 feet above sea level into 2022, while will force a first tier of water use reductions beginning Jan. 1.

The economic impacts to the states that tap water from the Colorado River are significant, with no relief in sight.

Lake Mead provides water to an estimated 25 million people in Arizona, Nevada, California and Mexico. The complex governance of the Colorado River Basin and its water priority system means Arizona and Nevada will be impacted first by the tier-1 reductions. Arizona will be subjected to an 18 percent reduction in the state’s total Colorado River supply, primarily impacting agriculture. And Nevada will need to maintain its existing 7 percent reduction until 2022.

Additional reductions will impact agriculture and municipal water if the water level in Lake Mead continues to decline. The next tier of water use reductions will be triggered if the lake level declines to 1,050 feet above sea level, which could occur by 2023.

This sweeping action begs the question: How did we get here for the Colorado River Basin? What is wrong and what is right about water in the Colorado River Basin when it comes to addressing water scarcity, quality and access to safe drinking water?

What we’re doing wrong

Blaming this on “the drought.” This is not a drought. The American West and the Colorado River Basin have been in the midst of a drought, mega-drought or persistent drought depending on who you ask. Yes, the region and the Colorado River Basin are in dire shape with no short-term solutions in sight. The reality is that the water shortage in the Colorado River Basin is part of the longer-term aridification of the American West.

On average, the Colorado River’s flow has declined by about 20 percent over the last century, according to a 2020 study by U.S. Geological Survey scientists. Over half of that decline can be attributed to warming temperatures across the basin, researchers said.

Without any significant reductions to planet-heating emissions, particularly from the burning of fossil fuels, the study found the Colorado River’s average discharge could shrink by 31 percent, compared to the historical average, by the middle of this century. This is a theme consistent with the recent United Nations climate report.

Public policy isn’t aggressive enough. It is inconceivable that there are still calls for voluntary reductions in water use. In July, California Gov. Gavin Newsom urged all Californians to cut water use by 15 percent. California and the American West are well past the days when one could count on voluntary reductions to save the day.

Mandatory water use reductions are the only path forward as there is no “return to normal” — mandatory reductions will drive innovation in water technologies (air moisture capture), financing of these technologies (crowdfunding) and business models (water as a service).

This is a matter of overallocation. The Colorado River Basin is overallocated. As the author of this article, “How Western States Must Change,” writes: “The ultimate problem facing the Colorado River Basin states is simple. There are more water rights on paper than there is water in the river.”

It is doubtful that the water supply could be increased to meet the current allocations let alone when facing the impacts of climate change.

The water accounting in the Colorado River basin needs an audit and reconciliation with current water supply and demand realities. This would be painful but long overdue. We can’t continue to hope for rain and new sources of water without addressing the demand side of the equation.

What is going right

Conversely, what is going right in the Colorado River basin? Fortunately, a few things are in play that I believe will influence innovation in public policy and engage stakeholders to accept the reality of water in the American West.

Water technology entrepreneurs and investors are increasingly engaged in finding and scaling solutions within the watershed and the West. For example, water technology hubs and accelerators such as WaterStart and ImagineH2O are identifying innovative technology solutions that can be deployed within the Colorado River Basin, the American West and globally. These organizations are getting more attention as the economic, business, social and ecosystem impacts are accelerating.

We are also seeing investors take interest in the Colorado River Basin through the first place-based water technology investment fund in the U.S. Market-based initiatives are emerging, such as the Veles Water Index, which benchmarks the spot price of water in the state of California. The transparency of this index fosters greater price discovery and allows for the creation of new tradable financial instruments to serve the needs of the California water market.

What’s more non-governmental organizations such as WWF, TNC and Business for Water are working with the private sector on corporate water strategies, consulting with the public sector on policy innovation and collaborating with other NGOs and civil society to explore solutions.

What the Colorado tells us

The Colorado River Basin is the “canary in the mine” for the future of water in the American West. If we don’t fix what is broken for the Colorado, we will feel the bite of climate change and resultant economic, business, social and ecosystem impacts at a scale exceeding the American dust bowl of the 1930s.

The status quo and installed base will have won at our expense if we fail to rapidly adjust to our new reality.

This content was originally published here.