In my twenties I had a love affair with an American painter, Marco.* We met in Oregon one summer and, though I lived in Australia and he in New Mexico, we began a long distance thing. He’d been born in New Jersey and had worked in advertising in New York before moving to Los Angeles where he became a titles designer in Hollywood. By the time I knew him, he painted big oils that were a little Rauschenberg, a little Pollock and a little Georgia O’Keeffe. Famous people collected his work. He was 20 years older than me, lived in the mountains of New Mexico and rode a Harley.

In the fall a year later, we went north together from New Mexico to Aspen, Colorado. We stayed in the holiday home of a friend of Marco’s, a filmmaker, who was out of town. The house was made of redwood and built in an aspen forest by a river full of trout. The river gave me ideas and the house was full of ghosts. I learned to trout fish there. And it was there I began work on a novel that would emerge, many years later, as The River Wife.

One night Marco took me to meet his old friend, Hunter S. Thompson.

“If you want to be a writer, you’ve got to meet Hunter,” Marco said. Then he added, “But whatever you do, do not agree to get in his car and go back to his house. We are not going back to the house.”

“Ok,” I said.

I had never read Hunter. I’d heard about Gonzo journalism. I’d vaguely heard about the drugs and the politics. I knew he was famous.

I was a long way from thinking of myself as a writer. In those days I had no published novel, no short story collection, nothing of note to back up Marco’s claim to my being a writer. I’d had a few short stories published. I’d drafted a first novel a few years earlier but I’d been disappointed with its failings and laid it aside. I worked as a copywriter in advertising for the Australian equivalent of Macy’s. I said I felt like a fake. Marco said it would be fine.

“Hunter will like you,” Marco grinned. “Believe me, he’ll like you!’

We arrived at the Woody Creek Tavern outside Aspen after nightfall and Hunter was already there at a table. Marco introduced me and we all sat down. Marco said, “Hey Hunter, Heather wants to be a writer, so I was thinking you two might like to talk.”

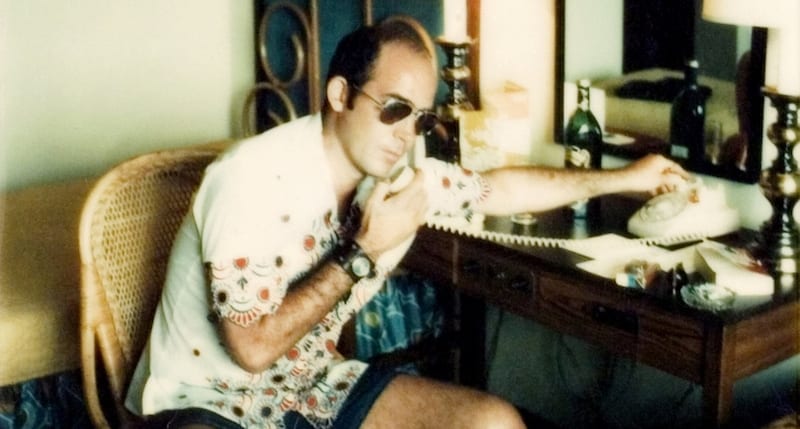

Hunter was wearing a dark shirt and a pair of tinted 70s style droopy-eyed spectacles. He nodded and, to my surprise and discomfort, Marco stood up.

“You two should get acquainted,” he said. “I’ll be over there. Take your time. Have dinner!’

I watched as Marco wandered across the tavern and joined a group of people who clearly knew him at the bar.

Hunter may have been sharing wisdom that would make me a great writer. He may have been gifting me with a lifetime’s worth of anecdotes that would fill up the dark days when the writing wasn’t going well.

Hunter asked if I was hungry. I nodded. He picked up a container of half-and-half from the bowl at the center of the table. He swiveled himself around and with unerring accuracy, he lobbed the small container at the barman some eight meters away. It hit the man in the side of the head. The barman looked over immediately at Hunter but, instead of being angry, he nodded. In a moment, a waitress arrived at the table and Hunter proceeded to order food. The ordering took a little time. Hunter kept thinking of things to add. Occasionally he fired a question at me about what I liked to eat, but didn’t wait for my answer. Meanwhile another waitress brought drinks.

And then Hunter asked, “Why do you want to be a writer?”

I guess I said something to the effect that it was the only thing I had ever wanted to do. Whatever it was, it got Hunter talking. Or maybe he would have talked anyway. He took off his glasses and he talked. And as he talked, he observed my face with the look of someone who was either seeing me from a long way away or far too close.

I suggested he talk a little louder but this only made him talk faster. I asked him to slow down a little. His voice descended into a slur of whispers. The slither and slide of his sentences blurred and purred across the table. It was a Jack Kerouac poem of consonants and diphthongs—serious, continuous and in Hunter’s case (but not Kerouac’s)—unintelligible. Food arrived and, while Hunter talked, he took bites from a burger, dipped into a basket of fries, made his way through a hot dog and several pieces of fried chicken.

His body was twitchy. His skin, now that I had time to observe it, had a sallow sheen. His hands jumped about on the table. Of course I tried to look like I understood the conversation. I nodded and smiled and ate and even laughed. This only served to enthuse Hunter even more.

Food continued arriving. Dishes piled up on the table, part or half-consumed, right down to pie. Hunter danced over words and around them. Only swallowing interrupted the pace of his monologue. Other than that, for an hour or more, it was one long stream of consciousness in which, from time to time, I could make out a single word – space – road – diesel – forget – interrogate – musical – snowstorm – intellect – water – salt. But the rest, as they say, was lost in translation.

Hunter may have been sharing wisdom that would make me a great writer. He may have been gifting me with a lifetime’s worth of anecdotes that would fill up the dark days when the writing wasn’t going well. He may have been telling me of every rejection he had ever received. He may have been giving me advice about managing publishers and deadlines or tough reviews. He may have been telling me about his latest work. Whatever he was saying, he was doing it in earnest.

His brain seemed to be racing up, falling down, screaming sideways and melting inwards. His eyes burned and his skin fruited beads of sweat that shimmered like condensation on a beer glass. From time to time he lobbed another half-and-half—once hitting the barman right between his eyebrows—and more food and beer duly arrived. The tavern filled, voices rose and fell around us, a juke box played and Hunter talked.

At the time Hunter was 56. In 12 years, he’d commit suicide by shooting himself in the head. Along the way, he’d be accused of handcuffing a woman to his stove for a day or two. He’d also write a few pieces for Rolling Stone, and he’d marry again. At the funeral, his ashes would be fired from a cannon by Johnny Depp. But back then, all that was ahead of him.

I knew this was a one-time thing, a rare and strange gift to sit there at a table with him on a week-night in Colorado. Yet I felt frustration and embarrassment, curiosity and wonder, worry, anger and finally irritation. Goddammit I was having dinner with Hunter S. Thompson and I could barely understand a word he was saying!

Eventually Marco returned, looking pleased that the two of us seemed to have had such a fine time getting along. We made to leave. On the debris of dishes, Hunter threw down a wad of American dollars. Marco gave him some of it back, but Hunter insisted on leaving a little more. Outside it was a clear, moonlit night and the Rocky Mountain air was sharp. Hunter entreated us to come back to his house.

“Let me drive you in my car. Marco can follow behind,” he enthused. The guy had charm then, and wavered only a little on his feet.

Marco gave me that look. The one that said, “I warned you.” He said to Hunter, “It’s late, another time.”

“It’s early. Really, it’s early. You’ve got to let me drive her. Don’t you want to take a ride in that?” he asked, waving his hand toward a green Chevy Impala glistening under a light in the car park.

I have a weakness for classic cars. At the time, back in Australia, I drove a pristine white ’65 Mustang with a powder blue interior. Marco knew this. He gave me a wry look.

“No,” he said to Hunter. “It’s not going to happen.” He assured Hunter we’d all catch up another night. Soon.

Finally Hunter seemed to understand that we were not going home with him, and he got in his car and drove away.

My last image of him was a solitary figure in a long, lean car fishtailing wildly but lazily up the Woody Creek road. He continued waving an arm in farewell until a curve in the road swallowed his tail-lights and the darkness consumed him.

*name changed