Fire chief Jay Teague discusses the wildfire preventative measures for the Four Mile Fire Protection District. (Video by Skyler Ballard and Katie Klann)

Developers built tens of thousands of new homes in Colorado’s riskiest areas for wildfires over the last decade, while local and state forest officials allowed wildfire protection plans across the state to age to the point they may no longer remain effective.

An analysis by The Gazette shows some of the most vulnerable areas of the state rely on some of the state’s oldest wildfire protection plans, putting those areas in peril for wildfire devastation.

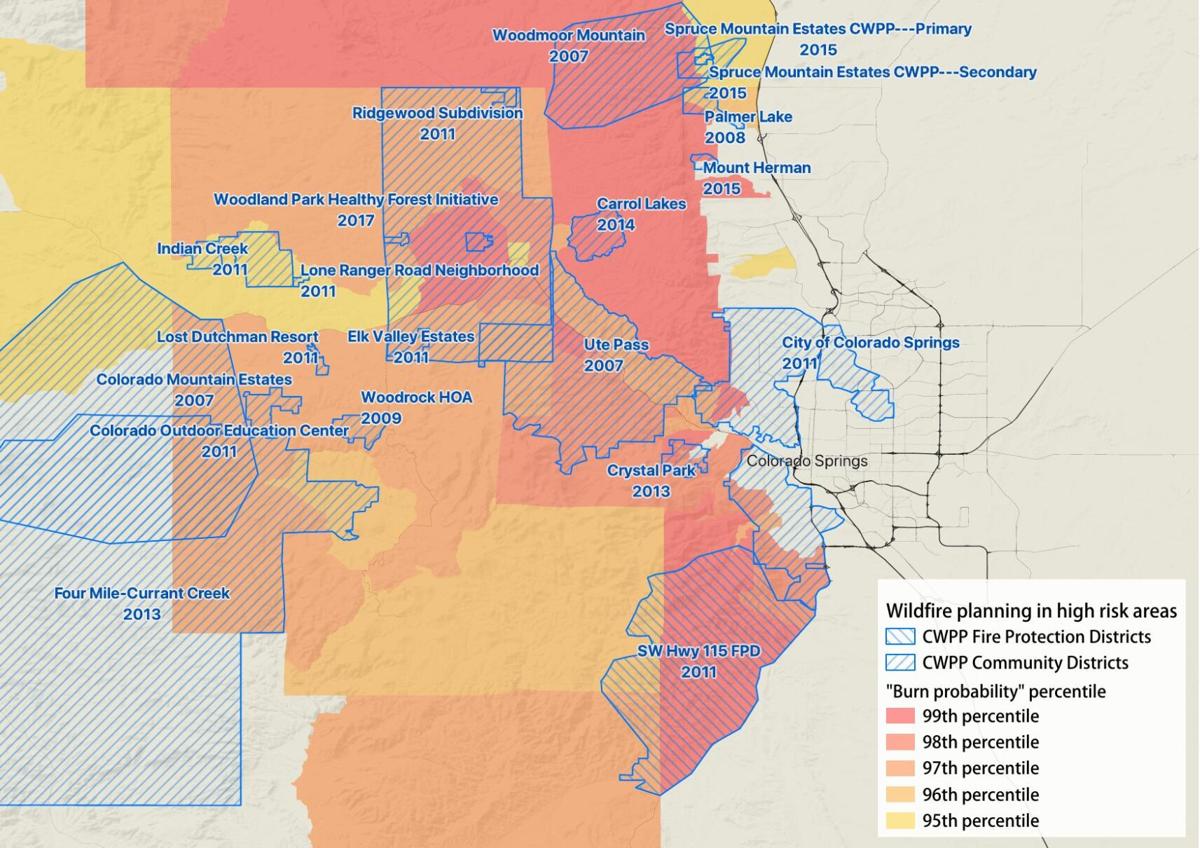

According to U.S. Census Bureau data, over the past decade, more than 2,000 homes, going from about 15,000 to about 17,000 homes, have been built in the top 1% areas of the state most at risk for wildfires, using wildfire burn probability data available from the U.S. Forest Service. At least one-third of those new homes are in areas without a fire mitigation plan updated in the past five years.

In the riskiest 5% of the state, more than 23,000 new homes have been built, bulging from about 100,000 homes to about 123,000. At least 70% of those new homes are in areas with plans that haven’t been updated in five years or more.

The Colorado State Forest Service, which provides oversight of the local wildfire protection plans, recommends that local officials update the plans at a minimum of every five years to remain effective. But the five-year update is only a recommendation in Colorado and not a requirement.

The fire documents — known officially as Community Wildfire Protection Plans —detail evacuation routes, subdivisions in hazardous locations and places where proactive mitigation work should take place. The Gazette found fewer than one out of every six of the 242 wildfire protection plans in Colorado were updated or created in the last five years. Roughly half of the plans are older than 10 years.

Colorado’s approach differs from that of the state of Idaho, as an example, where counties must update their protection plans at least every five years and where state officials annually review the plans to determine areas eligible for federal grant funding for mitigation work.

“The proposal for a cyclical planning process, built on a five-year rotation, is a valuable approach to an ever-changing wildfire risk,” wrote a team of researchers headed up by Stephen Miller, a law professor at the University of Idaho, who studied Idaho’s wildfire protection planning process and reviewed wildfire regulation and incentives in all Idaho cities and counties.

“By embracing a cycle of wildfire planning, local communities can feel confident that they have a procedural mechanism in place to continually rethink this evolving risk as their communities also evolve over time,” the research team found in 2016.

An updated Community Wildfire Protection Plan in Summit County helped attract $1 million in funding to clear defensible buffer zones, which in 2018 blunted a wildfire and saved more than $1 billion in homes and property in the Wilderness neighborhood, according to Dan Gibbs, executive director of the Colorado Department of Natural Resources.

Updated plans can save lives and property, said Dan Gibbs, executive director of the Colorado Department of Natural Resources. Summit County updated its plan in 2016, which Gibbs said helped attract $1 million in federal aid and local funding to clear out defensible protection zones around expensive housing in the Wildernest neighborhood in Silverthorne. That work ended up blunting a wildfire in 2018, saving 2,600 homes and property worth about $1 billion, he said.

“I would urge communities to take a hard look at their plans,” Gibbs said. “These are not something that should just be put on a shelf. Land use decisions can dramatically change a focus area. If you put in a new neighborhood, should that be incorporated into wildfire planning? You bet it should. These plans are living, breathing documents that need to be updated regularly.”

The local wildfire mitigation plans have grown old and languished even as wildfire perils have become riskier and more acute in Colorado as climate change continues to exacerbate and create persistent drought condition, according to one key state planning document. Large swaths of dense forest land in Colorado have become home to dry, volatile fuels, warns Colorado’s State Hazard Mitigation Plan, which guides state planning for the the years 2018 through 2023.

That plan identified wildfire and drought as two of the top three hazards facing communities in the state. And the other top hazard in the state, flooding, often is exacerbated when wildfires destroy natural protective habitats, the document states.

Four Mile volunteer firefighter Paul Jackson follows wildland Lt. Carl Sanders through the dense ground willows in the Bear Trap Ranch subdivision Monday, July 26, 2021, while patrolling the area northwest of Cripple Creek. The willows and grasses in the area are three to four feet high this year because of a wet spring and early summer. Fire Chief Jay Teague said before COVID-19 the subdivision had a year-long population of 30 percent compared to 70 percent today. A combination that could be deadly if August is dry. (The Gazette, Christian Murdock)

From 1984 through 2017, wildfires caused more than $1.3 billion in insured dollar losses, with the amount of those losses increasing dramatically since 2010, according to the planning document. Last year, three of the largest wildfires in the state’s history burned over 600,000 acres in some of the state’s most pristine watersheds and iconic areas, including Glenwood Canyon and treasured forested mountain landscapes.

Such losses prompted the state legislature to pass a $29.8 million wildfire-mitigation package this year that Gov. Polis signed into law amid concerns Colorado’s conditions have progressed so severely that the state no longer has wildfire seasons, but instead faces a year-round wildfire threat, where mega-fires can occur from spring through late fall.

The legislation, SB21-258, will boost grants the state can make available for local mitigation work and also provide funding to the Colorado State Forest Service to help local communities and fire districts update their wildfire protection plans. The legislation also included $200,000 for the Colorado Department of Natural Resources to work with federal officials to develop a statewide wildfire risk assessment that will determine where mitigation work is most needed.

Despite the worsening wildfire conditions in Colorado, The Gazette found more than 20 instances where officials allowed protection plans to become outdated in high-risk areas despite significant growth in housing in the areas those protection plans cover. The analysis found areas in Jefferson, Douglas, Teller and El Paso counties among those most at risk due to wildfire probability, significant growth in housing and outdated planning.

Teller County, which claims to have created the first wildfire protection plan in the state in 2005, last completed an update in 2011 and is currently updating its wildfire mitigation document. Jefferson County’s plan, which is also is being updated, dates back to 2012. El Paso’s plan is more than nine years old. And Douglas County’s, which also is being revised, was created in 2011.

All those counties have local municipalities and local fire protection districts within their borders that also have outdated wildfire protection plans, some of which are at least 14 years old.

Kevin Michalak, the fire management officer for the Jefferson County Emergency Management System, said he was surprised when he was hired for his position in February to discover the county’s wildfire protection plan was so old. He immediately pushed for an update, which he predicted will take more than a year to complete.

“It was the first thing on my list,” he said.

“With the amount of people moving in the areas, things have changed with population density and what areas we were looking at before as opposed to now,” Michalak said.

He said he worries whether evacuation routes can handle all the population growth.

One area of concern for the Inter-Canyon Fire Protection District, which also is updating its 2007 fire protection plan, is an aging population, said Daniel Hatlestad, the battalion chief for the mostly volunteer fire department located in Jefferson County. He said mitigation work is mostly done by residents, who chop down overgrown trees and brush on their own for fire crews to collect.

“The need for mitigation is never ending,” Hatlestad said.

Wildland Lt. Carl Sanders, left, Capt. Anthony Benavidez, right, and Fire Chief Jay Teague, background, displace a stone firepit Monday, July 26, 2021, while a crew from the Four Mile Fire Department patrols the BLM land in their district after a weekend in search of smoldering campfires. The fire department began the weekly patrols to decrease the fire risks. (The Gazette, Christian Murdock)

Douglas County’s plan is so old the software used to model risk areas when the plan was created in 2011 no longer works, which has complicated the work on updating the plan, said Jill Welle, the senior wildfire mitigation specialist for Douglas County.

“You don’t just snap your fingers and click on Google and have the mapping come up,” she said. New homes have gone up in Douglas County and forested areas have dried out and become major risks since the creation of the county’s plan in 2011, but officials still are addressing needs, she said.

Just because a protection plan is outdated doesn’t mean mitigation work isn’t underway, said Randal Johnson, the fire marshal for the Larkspur Fire Protection District, which covers about 109 square miles in Douglas County.

Local officials in Douglas County, despite old plans, still successfully snagged grant money to treat and clear Douglas fir trees vulnerable to wildfire due to Tussock moth larvae destruction, which struck forested areas in 2014 and 2015, Johnson said. But the work underway will address only a few hundred acres of the tree devastation, he said, and more than 8,000 acres of trees in the area, mostly in Pike National Forest, have been damaged and become a potential fire hazard material.

The Perry Park community, where Johnson lives, which is covered by the Larkspur Fire Protection District, is among the 1% riskiest areas of the state for wildfires, according to the federal data analyzed by The Gazette. But Perry Park’s community wildfire protection plan hasn’t been updated since 2007 despite hundreds of new homes going up in the area, Johnson said, and many of the new residents come from areas of the nation unfamiliar with wildfire risks. He recalled how Perry Park residents had to evacuate when wildfires raged nearby in 2002 and said he hopes people will be prepared when wildfires inevitably flare again.

“We’ve had people come in and move here and try to landscape the same as they would a suburban area,” he lamented. “To do it right, you need to have a five- to six-foot wide non-combustible zone perimeter around the house.”

In Teller County, the fire risk is driven not only by population growth and dense forests, but by the 15,000 to 20,000 campers and visitors that come on weekends and holidays and leave campfires smoldering, said Don Angell, director of the Office of Emergency Management. Teller County has an out-of-date community wildfire protection plan, last updated in 2011, a document it is updating now. But it’s also organized other efforts to address fire risk.

For example, crews go out after every weekend and holiday to look for and put out fires that weren’t properly extinguished with water or dirt. After the 4th of July weekend, crews led by fire protection districts put out 20 smoldering campfires to make sure they didn’t grow into an uncontrollable blaze, Angell said.

Some of the fires are built with just a few rocks around them instead of within a proper fire pit, making it easy for them to jump out, Four Mile Fire Protection District Chief Jay Teague said. The crews also find fires are started on large vacant lots within subdivisions by campers who own or are renting the property, he said.

Those fires could easily grow into a raging blaze within the 65-square-miles of the Four Mile district south of Florissant and northwest of Cripple Creek that is considered the driest part of Teller County, he said.

“We are seeing more and more trees that are unhealthy and starting to die off,” he said.

In addition, some subdivisions in the Four Mile district only have one access road, an issue the Office of Emergency Management is trying to address throughout the county, Angell said.

“It just makes them all high risk,” Teague said.

To help address the needs in the district, Teague has worked hard to build his department. While it can only afford a handful of paid staff, the department has recruited more than 60 volunteers, up from about six a year and half ago.

“What I’ve focused on is making the fire department the social heartbeat of our community,” he said.

The district holds concerts and events to help get people involved and interested in its work, he said.

He is also trying to encourage subdivisions to write their own wildfire protection plans and start groups to organize mitigation efforts, he said.

But even organized neighborhoods can face challenges with fire mitigation and prevention.

The Bear Trap Ranch subdivision, also in Teller County, posts signs informing residents of the fire danger at the entrances and discusses the risk at quarterly meetings, said Victoria Carnahan, president of the landowners association.

Still, only about half the property owners mitigate their 20-acre lots in the heavily wooded area, she said. Part-time residents tend to be uneducated about the importance of the issue, she said.

“We have some that do great, and some do nothing,” she said.

Out of the 400 people who live in the subdivision only about 12 to 15 volunteers are available to help keep areas of neighborhood interest, such as the land alongside roads, trimmed back to help mitigate fires, she said.

Despite the wildfire risk, Carnahan says she loves her wrap-around view of three mountain ranges, and that’s one of the reasons she stays in the remote subdivision with only two roads in.

“We lived in the city, and we moved up to the mountains to get away from the city life, to get away from the political issues and have the privacy and be left alone,” she said.

The Colorado State Forest Service can help communities and fire districts that want to update their protection plans, some of which exceed 200 pages in length, said Daniel Beveridge, fire fuels and watershed manager and the state forest official who monitors community wildfire plans in Colorado. But he said local control is strong in Colorado, and that residents first contact should be local officials if they fear their area does not have an up-to-date protection plan.

“If local residents are interested in seeing to it that these plans are updated and modernized, the best course of action would be for those folks to reach out to their local authorities that are most appropriate when it comes to providing, you know, guidance and direction related to these matters and just simply ask the question,” Beveridge said.

In Colorado, local officials saw the state forest service’s role as so minimal that they didn’t even alert the forest service when they updated wildfire protection plans on at least 22 occasions, The Gazette’s review found. Even when plans were updated, they often weren’t done so regularly or consistently.

In contrast, the state of Idaho requires counties to make their community wildfire plans part of their “all-hazard” mitigation plans, which communities are required to file with the Federal Emergency and Management Agency to qualify for certain forms of non-emergency disaster federal aid.

Synchronizing wildfire planning with the all-hazard mitigation process means counties in Idaho are required to update their wildfire protection plans every five years. County and state officials also review the county plans annually to keep proposed mitigation work in the plans on track.

“This is the way to help inform the most efficient use of scarce resources,” said Tyre Holfeltz, Idaho’s wildfire risk mitigation program manager, who works with counties in Idaho to ensure they are updating their wildfire protection plans.

He said that within the next two years, all the counties in Idaho will have their plans updated and on the five-year hazard mitigation planning cycle. Idaho officials also review the wildfire protection plans to prioritize areas best suited for grant applications for federal mitigation aid, he said. Holfeltz said he makes sure counties are working on the mitigation projects identified in the wildfire protection plans.

“We want to see that these plans are being utilized or implemented,” Holfeltz said. “It’s to show progress. It allows us to go to a check list and see what we’ve accomplished and add additional work we endeavor to complete.”

This content was originally published here.